“YESTERDAY, HIERARCHY WAS THE MODEL; today, synergy is the mandate. Yesterday, leaders commanded and controlled; today, leaders empower and coach. Yesterday, employees took orders; today, teams make decisions.” Former President of India A.P.J. Abdul Kalam, was telling project managers in Bangalore at the Project Management Conference last month how education could affect leadership. He might well have been talking of the contemporary Indian workplace. Companies these days tend to be a hybrid of traditional stereotypes and the modern system of management. The ongoing tension and clash of mindsets is creating a whole new way of working—call it the millennial Indian work ethic, if you will.

The traditional Indian traits of hard work, perseverance, and frugality are also undergoing a dramatic change. Once, a job was seen as an unbreakable contract between employee and organisation. Till the early 1990s, having a secure office job was the pinnacle of achievement; getting ahead in the office hierarchy was simply a matter of staying in the same place for long enough. Then came Manmohan Singh and his call to open the economy. The influx of multinational companies saw the introduction of a work culture based on productivity not longevity. It gave rise to a new breed of workers who grew up in a pre-liberalised country, but started working in a post-licensed environment.

In any office there’s a marked tension between them and the pre-liberalisation generation—those who grew up and began working in that era. Add the new entrants to the workforce—the generation that has grown up post-liberalisation—and the generation gap is even more marked. “The new generation is more worried about entitlements than duties,” says an old-school manager huffily.

The Chinese are going through a similar clash of generations. According to a July 2010 report by All-China Federation of Trade Union, the only recognised trade union in the country, the younger generation—known as the “post-’80s generation”—is more willing to file complaints when their rights are violated and less fearful of retaliation than their elders.

Apart from the generations—and there are three at work—any generalisation about Indian work and management culture has to account for the differences in size, ownership, and the broad characteristics of the business in question. Thus, a large software company with a multinational presence tends to operate on a more egalitarian basis than a small, family-run Old Economy firm.

What does this new way of working involve? For one, the 9-to-5 job is largely a thing of the past. Working from home is seen as acceptable, even environmentally sound. Part-time job seekers and freelancers are no longer viewed with suspicion. Jeans are okay in some workplaces, as are casual shoes. In most offices, what people wear is no longer considered as important as what they do.

Of course, none of this happened overnight, and not all of it has happened everywhere. There’s still a huge difference between what people want from their workplaces and what they do to get there. So even as a manager talks of working for gender equality, he may promote a man instead of an equally qualified woman. It is this kind of dichotomy that makes the Great Indian Office what it is.

Almost every nation has its own defining work characteristic or distinct work culture, some so distinct that they are stereotypes: The super-efficient German, the laid-back Italian, the insular Japanese ... So far, India has not had anything like a defining national work culture. If anything, definitions of Indian work culture have veered between the extremes of “lazy and inefficient” to “hardworking and diligent”. Indians working abroad or for companies based in the West have traditionally shone, while those working in India, often for Indian companies, believe they have nothing to prove to anyone, and are therefore less likely to go the extra mile. But with Western companies entering India, the average worker has had to change his ‘easy come, easy go’ attitude. And as Indian businesses get increasingly global, an international work ethic has also come into play, adding a new layer to existing tensions.

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN INDIAN WORKERS and their foreign counterparts can be stark. Swedish workers, says Inderjit Sial, country head of Swedish defence company SAAB, will definitely take at least one long vacation every year. “But even if you ask an Indian to take a six-week paid holiday, he will never do so. He fears that by asking him to go on leave, the company is looking for ways to throw him out.” Sial says the Indian worker is, on the whole, more insecure than his foreign counterpart.

“What makes the Indian work ethic unique, as far as senior managers are concerned, is that while their minds are intellectually aligned to the Anglo-Saxon system, their social alignment is highly Indian,” says R. Gopalakrishnan, director, Tata Sons. Gopalakrishnan has seen plenty of this in his 31 years in Hindustan Lever (now Hindustan Unilever). He was chairman of Unilever Arabia, and became the vice chairman of Hindustan Lever, before moving to Tata Sons as executive director.

A large part of what is seen as Asian (and Indian) inefficiency stems from the fact that most employees wait to be told what to do. They prefer to be led than to lead. One of the most common excuses given for much of corporate India’s failings is that the entire system is rigidly hierarchical and undeniably patriarchal. Of course, much of the blame for this is laid on social conditioning and our colonial hangover. Both the Vedic and the Confucian philosophies stress deference to parents, seniors, or those in authority. “Being polite and respectful to elders also instils a desire for clear supervision and explicit instructions, causing the need for hierarchy,” says Amit Kumar Sharma, professor of sociology at Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University.

Since hierarchy is so important, the boss is seen as all-powerful. “The major discussion in the company was who had managed to get into the boss’s inner circle. It was not so much about delivering results as about being close to the boss,” says a senior manager who worked at a family-run steel business, where the boss was the owner. “He would lose his temper in public with staff at all levels even for minor mistakes,” he adds. This led to an atmosphere of fear when the boss was around, and a breakdown of discipline when he was away. There was even an early-warning system: The imminent arrival of the boss was announced on the intercom, so that workers could begin looking busy. The manager quit in less than a year, and joined a multinational company in a similar business. “The cultures are so different that you don’t realise you are working in the same country,” he says.

So what is it that keeps one company in the dark ages, while another moves on? In many cases, it has to do with who runs the show. To keep their jobs, Indian workers, by and large, believe that the boss wants to see them working all the time. No wonder then, that BlackBerries are on 24/7, and weekends are rarely for pleasure or family. “That’s also connected to the lack of economic security because we do not have the dole or a robust social security system, like in Britain,” says Santrupt Misra, human resources director at the Aditya Birla Group. “So, minus employment, you are really nothing. You cannot afford to disconnect what happens in your work from the rest of your life.” Sial adds: “So, you don’t go on a vacation but hang around your chair all the time.”

In general, a family-run company is far more parochial and paternalistic than one where ownership is diverse. The head of the family is generally the head of the company, and he hands out rewards or punishments as he sees fit. As Milind Sarwate, group CFO of Marico, explains, “I am expected to play the role of an older brother to the existing younger employees and that of an uncle to the new workers who have joined the organisation. And Harsh Mariwala [Marico’s chairman] would be like an older brother to me.” With family and work so intertwined, it becomes difficult for old-school employees to say “no” to the boss. This is also something that begins in childhood; an Indian child is brought up to never say no to his father. “So we set unrealistic goals and deadlines for ourselves and, when we inevitably fail to deliver, we lose face and disappoint our bosses,” says Ravi Uppal, CEO of Larsen & Toubro (L&T) Power. Before L&T Power, Uppal was ABB’s president of global markets in Zurich, Switzerland. He was also the founding managing director of Volvo India.

A strongly paternalistic environment is not, however, an entirely bad thing. “Today, as I actively engage with young professionals, I am more understanding of their impulsiveness and immaturity, and give them extra leeway for their behaviour,” writes S. Ramadorai, who retired as MD and CEO of Tata Consultancy Services, in his recent book The TCS Story...And Beyond.

That leeway might inspire the young employee to do better, but it might also lead to a general assumption that the boss or management will always forgive minor transgressions. “The feeling is that the company is my family and I am willing to do anything for it, so if I am late for a meeting, I expect the management to overlook it,” says Sarwate.

“Since most Indian organisations have no well-defined rules and processes or expectations from the worker, it is far easier for the worker to break the discipline. If there were codified rules, he would follow them as workers do in other parts of the world,” says Sandeep Goyal, the man who is credited with bringing the Japanese advertising firm Dentsu to India and making it a success.

WITH MORE AND MORE INDIAN COMPANIES going global, the importance of a set of rules, systems, and processes is being felt. The younger generation of workers seems more process-driven, while the older generation is able to work even when processes break down, or there are no processes at all. And since most workplaces are run by a generation that values verbal instructions over written ones, there’s often a clash of ideas. The benefits of a process-driven workplace are self-evident, but there’s no such intuitive argument in favour of the old school. Sumit Mitra, executive vice president, corporate HR, Godrej Industries, however, defends the culture of ambiguity, saying that it makes a worker multitask and shoulder more responsibility, unfettered by the idea of certain jobs only for certain designations. “Obviously, then, he will have a far better understanding of the working of the organisation, which will help make the company far more resilient,” he says.

But the general trend is to move to less hierarchical structures. “The military kind of pecking order is fast disappearing with greater democratisation of organisations,” says Uppal. He adds that many organisations are deliberately being made flat and decision-making is largely consensual. Delhi-based Apollo Tyres, for instance, is trying to create a completely flat structure at its Chennai factory. “There is no concept of a worker or manager there. There is only one management team; all the workers are engineering graduates,” says Neeraj Kanwar, vice chairman and MD, Apollo Tyres. The method is democratic: Each team leader is appointed for two years, and is replaced by a new leader selected on the basis of performance. “The rotation process infuses new blood, energy, ideas, and drive into the organisation,” adds Kanwar.

However, this flat organisation has not found many supporters. Kanwar admits that his company has been trying to adopt it for two years, but employees prefer designations and all the trappings—the corner office, office car, and so on. “Job designations still remain an important part of an Indian’s identity and a yardstick for judging his position in society,” says G. Srinivas, associate professor of sociology at Jawaharlal Nehru University.

Will people quit if they don’t see any obvious signs of success? “Since good professionals are spoilt for choice today, they want everything immediately: Money, power, growth opportunities, global exposure ... every day, they want to know what the company is doing for them,” says Shailesh Deshpande, associate vice president, corporate HR, Godrej. A 30-year-old manager who asked not to be named says his priority is getting due recognition at the workplace. “Money and other benefits automatically follow—a bigger car, company flat, etc. Most of us spend nine hours in office, three hours in travelling, six hours of sleep, and just six hours with our loved ones. So, getting the best out of the workplace becomes very important.” Kanwar, however, still believes in the virtues of a flat system and says he’ll persevere; once the initial resistance is overcome, he says the workers too will see the benefits

THE GENERATION THAT BEGAN WORKING in the 1990s has embraced a career model of rotation between employers, rapid career advancement, global postings, and demands higher wages. “If, around 1999, candidates for the top job spent at least five to eight years in the job, today I get profiles with just three to five years of experience,” says Govind Iyer, partner at Egon Zehnder, a global recruitment firm.

It’s not just workers who want to move on; companies are no longer keen on lifelong employees. “Lateral hiring at the higher management levels and employing casual workers on the shop floor is increasingly popular,” says a top executive of a headhunting firm. As CEOs and senior managers face the heat from shareholders on a quarterly basis, they need to maximise returns constantly. So, there’s an urgency to find managers who can deliver. “The previous strategy of training a management trainee to become a leader is increasingly giving way to lateral hires,” says Zubair Ahmed, MD, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK). He himself hired several people who were already specialists in their fields when GSK decided to move into making and marketing instant noodles.

However, while the Indian workplace has changed to accommodate different ideas, workers have not adapted as well. For example, while Reliance Industries (RIL) has hired more than 100 temporary senior managers at astronomical salaries to take care of existing and new businesses including 4G, broadband, retail, etc., most are expats. Few Indian managers want to get into this space, says Iyer, because Indians want job security even at these levels. Also, while nobody comes out and says it, there’s the belief that non-Indians (read: Western) work better.

Another area where there’s been little change, despite legal intervention, is in hiring minorities. The average Indian likes to believe that caste is a social structure and does not affect work. However, social scientists burst that bubble some years ago. In October 2005, as part of a study, three Delhi-based social science researchers, Sukhdeo Thorat, Paul Attewell, and Firdaus Fatima Rizvi, applied for 548 jobs based on ads in prominent national dailies. The applications were similar in all respects—education, experience, etc.—except the name of the applicant. A third went out with upper-caste Hindu names, a third with obviously Dalit names, and a third with Muslim names. The responses were telling: Calls for interviews or entrance tests went to all the upper-caste applicants, 67% of the Dalits, and only 33% of the Muslims.

These results, published in a paper entitled Urban Labour Market Discrimination by the New Delhi-based Indian Institute of Dalit Studies, do not surprise some corporates. “When you hire people from a similar social background you cut down on transaction costs,” says Marico’s Sarwate. It’s easier for people of similar backgrounds to adjust to the existing work environment than people from different backgrounds, he explains.

Others, however, claim that their companies take affirmative action when it comes to hiring minorities. “If we have three applications of the same calibre—one from a Dalit, one from a woman, and one from an upper-caste Hindu—we’d rather hire the woman or Dalit,” says Ahmed. L&T Power’s Uppal agrees, adding that as long as all other qualifications are equal, companies such as his rarely discriminate on the grounds of caste or community.

However, academics and activists say these responses could be mere lip service since companies are unwilling to share details about how many they actually hire from minority groups. Ashwini Deshpande, professor of economics at the Delhi School of Economics and author of the recently published The Grammar of Caste, is convinced that caste-based discrimination in the workplace “is neither a relic of the past, nor is it confined to rural areas, but is very much a modern formal-sector phenomenon that begins at the recruitment stage”, as the Thorat-Attewell-Rizvi study showed.

GENDER DISCRIMINATION ALSO BEGINS HERE. More often than not, those involved in hiring decisions cite seemingly logical reasons why women should not be hired. Among the most frequent are: “She’ll leave to get married and not come back, so we’d have wasted valuable time and resources training her” and “She’ll go on maternity leave and not return”. If a woman manages to make it through a recruiting process that’s stacked against her, she’ll have to learn to put up with overt and covert harassment in the workplace. This is something that hasn’t changed, even with economic liberalisation.

“The traditional Indian male is still a little uneasy working with women because he finds it difficult to manage the contradictions of his life. From early childhood he has been taught to be the man of the family taking all major decisions, and then suddenly he not only has to share power and authority but also take orders from women. It’s quite a culture shock,” explains Rekha Pappu, coordinator of the Anveshi Research Centre for Women’s Studies in Hyderabad.

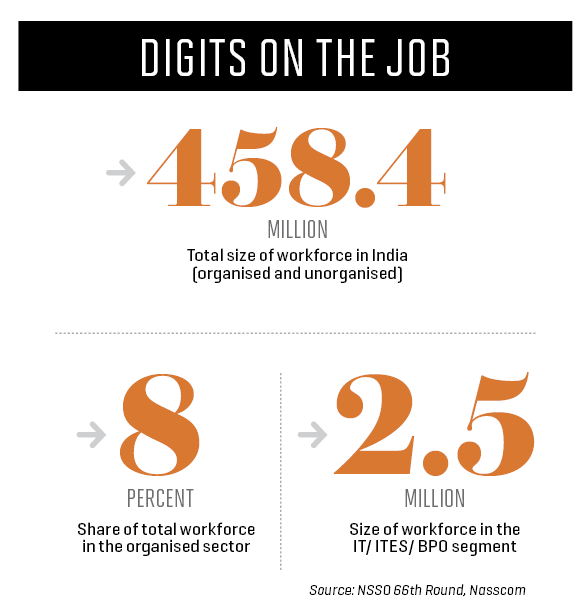

The 66th National Sample Survey found that in 2009-10 there were only 127.3 million women in the workplace; that’s around 28% of the total workforce. The share of urban women was even lower—just 19%. This despite the fact that it makes business sense to have a diverse workplace. Roopa Purushothaman, a former vice-president at Goldman Sachs and now head of research at Future Capital Holdings, an investment firm, calculated that if 35% more women were to enter the Indian workforce (its full potential), it would add $35 billion (Rs 1.68 lakh crore) to India’s gross domestic product, and make Indians 5% richer by 2015, and 12% more by 2025.

The good news is that with liberalisation and the entry of multinationals, Indian companies have been forced to give serious thought to diversity in the workplace. Some have implemented policies on sexual harassment, flexible working hours, and leave, while others offer crèche facilities, parenting workshops, and women’s forums.

In fact, Godrej pays recruitment firms extra to find women candidates. “It is our own way of showing affirmative action because we realise that our workforce is skewed towards men,” says Mitra. It has worked to a limited extent. Similarly, IBM Global Process Services has women only recruitment drives and pays higher referral bonuses for diversity candidates.

The problem that women face is also that of being overlooked for promotions and bonuses if they drop out of the workforce temporarily, usually on maternity leave. The rationale behind this is that employees who did not take leave spent more time on the job and were therefore entitled to be promoted. It really has very little to do with productivity or efficiency. Tata’s Gopalakrishnan lashes out at time-bound promotions such as those in the administrative services. “Whether you become a secretary in the government or the chief of the army staff is determined by the year that you joined the services. It is completely crazy and such a practice exists nowhere else in the world.”

This “crazy” practice has its roots in the strong belief in a socialistic pattern of society, which dominated the thinking of the country’s political leadership soon after Independence. This led to the concept of a planned economy, which gave public sector enterprises a commanding role. Private enterprises, reduced to playing a secondary role, were hobbled by all kinds of rules, laws, and regulations. Those who entered the workforce in the 1950s and ’60s gravitated towards government jobs associated with manufacturing, infrastructure development, etc. For that generation, job security was the primary consideration; they were happy with a cash-low, benefits-heavy model, where promotions were based on tenure rather than merit.

Mohit Kapoor, founder, CEO Apps Kiosk, a Delhi-based apps provider, has worked for eight years with U.S.-based Alcatel, and had a stint with home electronics company Haier, and then with Videocon. He has seen how multinationals deal with the issue of corruption both in India and abroad. “You can’t blame Indians for being corrupt,” he says. “After all, the majority grew up in the licence-raj days.” However, that is changing. Most Indian and multinational companies today have clear rules about what is negotiable and what is not. “There are certain rules that are clearly not negotiable. For instance, we will not pay bribes even if it means walking out of a deal,” says Sarvate of Marico.

Multinationals have little choice because most of the rules are made in the corporate headquarters. Says SAAB’s Sial: “Swedes do not understand the concept of black money or a parallel economy.” Kapoor, however, says that this is not necessarily true for all multinationals. Many MNCs employ agents, who charge a “market access fee”, he says. “How he uses that money is no longer your concern,” adds Sarvate.

But this attitude is changing. Kalam says a lot of this change has to come from the top. “The leader should not be a manager, but a mentor; [he should] change from a director to educator. For a vibrant nation like India, the thrust will need to be on creative leadership.”

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required field are marked*