ON A JUNE EVENING IN Delhi’s Shangri-La Hotel, Muhtar Kent, president and CEO of the Coca-Cola Company, dressed casually in khaki slacks and a jacket, climbs the stage in the ballroom to make a short speech on Coke. It’s the launch of the second season of MTV Coke Studio India, a hugely successful platform that brings together disparate musicians. He talks about the importance of India in Coke’s scheme of things, its investments here, and why working for Coke is such fun. It’s a short but effective speech—the audience, which includes Delhi chief minister Sheila Dikshit, and the chairman of the Unique Identification Authority of India, Nandan Nilekani, cheers at almost everything he says.

India is special to Kent. His father, Ismail Necdet Kent, was Turkey’s ambassador here and Kent spent a part of

his childhood between 1960 and 1962 in New Delhi.

These days, he’s looking at India as one of the key emerging markets that will lead the way to growth as markets

such as the U.S. slip. Earlier in the day, at a press conference, Kent had said, “Our India story is one of a remarkable turnaround. The country now aspires to be one of the top five markets [for Coca-Cola]. In 2005, it was at number 16 or 17.”

For starters, Atlanta has opened its wallet and plans to invest $5 billion (Rs 28,505 crore) in India by the end of the decade. That’s more than double the amount Coke has invested since it re-entered the country in 1993 and is an indication of the opportunity the company sees. The money will go into building a stronger backbone for the company—rural distribution, cold storage, trucks, plant expansion, equipment purchases, and marketing.

Kent’s man on the subcontinent, Atul Singh, the affable-looking president of Coca-Cola India, who guzzles seven cans of Diet Coke every day, refuses to “get into specifics like what percentage we have to grow at. But, clearly, India has to be a strategic market given the demographics and the opportunity we have for the Coca-Cola Company to achieve its targets globally.” (By 2020, Kent wants to double business globally—from $95 billion in 2010 to $200 billion.)

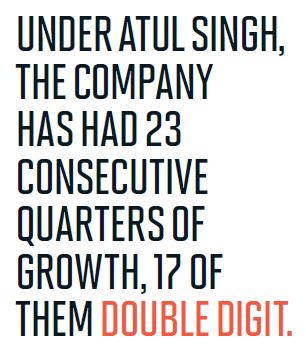

RECRUITED FROM COLGATE-PALMOLIVE in 1998, Singh was elevated to his current role in 2005, around the time the company was embroiled in the pesticide controversy. (In 2003, the Delhi-based Centre for Science and Environment alleged that 12 brands of beverages from PepsiCo and Coca-Cola contained pesticides.) There were also allegations of excess ground water usage at bottling plants such as Plachimada in northern Kerala. Those troubles have mostly blown over (though Coke is still not bottled in Kerala), and under Singh’s watch, the company has had 23 consecutive quarters of growth, 17 of them double digit, making India Coke’s best-performing market. Sales in the last quarter grew 20%.

But to fulfil its lofty targets, it’s crucial for Coke to improve the availability of products in small towns and rural areas. Currently, Coke products are available in less than 2 million of the 5 million plus retail points. It is looking at combining innovation in both distribution (solar-powered coolers in areas without electricity) and products (Fanta is now available as a mix-and-drink powder).

Home-grown brands will play a crucial role. Take Thums Up, the cola drink acquired by Coca-Cola from Parle in the early 1990s. It has lived up to its “Taste the thunder” slogan and, indeed, stolen the thunder from the company’s flagship beverage, Coca-Cola, and rival Pepsi, and dominates the Rs 11,000 crore aerated drinks market in India. Figures from Euromonitor suggest that Coke has just 8.8% of the carbonated soft drink market. This is nearly half of Pepsi that has 15% and trails Thums Up and Sprite that have 16.5% each.

There has been a revival of old local brands that still enjoy high recall: Citra, a clear, lemon drink from the Parle bouquet, has been given a second lease of life in some markets, such as Gujarat, as part of a pilot launch. (Only Thums Up, Maaza, and Limca from the Parle stable were continued, while Citra and Gold Spot were withdrawn.) Coke is hoping that Citra, priced to compete with cheap local drinks, will help increase per capita consumption of sparkling beverages in India.

According to Pratichee Kapoor, associate vice president, food and agriculture, of consulting firm Technopak, India is set to continue its high-growth trajectory in the sales of beverages of all types. She believes that Coca-Cola and Pepsi, with their multiple brands and distribution muscle, shouldn’t find it hard to push the limits of growth. She is especially bullish about the growth of juices, diet colas, and energy drinks among consumers, especially in cities.

Coke is also experimenting with local flavours. One of the most popular drinks, usually made at home in summers, is a ‘mango shake’—a mango-and-milk concoction that’s seen as energy-boosting and nutritious. Coke India’s food scientists have reproduced this beverage in their New Delhi lab by mixing Maaza, Coke’s thick mango drink, with milk. It’s called Maaza Milky Delight and is being test-marketed in Kolkata.

A couple of years ago, Coke came out with its version of another staple—the unpretentious lime juice or nimbu paani—and launched Minute Maid Nimbu Fresh.

Adding popular local flavours to its product portfolio is a part of Coke’s worldwide strategy and crucial to Kent’s vision of an agile and entrepreneurial organisation (see ‘The New Coke’).

But the thrust on home-grown beverages won’t come at the expense of its international products. Brands such as Schweppes continue to be introduced, and Singh says there are more to come from the company’s 3,500-strong beverage portfolio.

THAT EXPLAINS WHY the biggest marketing push this year has been reserved for the Coca-Cola brand. Early this summer, in a surprise move, the price of a 200 ml bottle of Coca-Cola was brought down from Rs 10 to Rs 8 in many markets, even though other brands continued with their earlier pricing. Meanwhile, newspaper reports suggested that the company had asked bottlers and trade partners to ‘push Coca-Cola ahead of other drinks this summer. Singh sidestepped the question.

On the advertising front, too, Coca-Cola has received a bigger push than its other brands. Lowe Lintas has been brought in to share the account with incumbent agency McCann Erickson. Sachin Tendulkar, earlier the ambassador of Coca-Cola India, is now the face of Coca-Cola, the beverage. R. Balakrishnan, chairman and chief creative officer of Lowe Lintas, says the drink’s positioning—with its ‘Open happiness’ slogan— is something that resonates well in India. He adds, “The current ad featuring Tendulkar is the first that we’ve been asked to do for Coca-Cola. We’ll wait and see how it works.”

All these strategies are aimed at increasing per capita consumption, something Kent is known to demand. Currently, India’s per capita consumption is just a minuscule 12 bottles a year compared to Mexico’s 675. As Singh says, the opportunity is huge. And there’s promise: According to Coke’s annual report for 2010-11, India recorded a 12% growth in unit case volumes, thanks to a 12% growth in sparkling beverages and 11% growth in still beverages. Sprite grew by 17%, Thums Up by 15%, and Coca-Cola by 11%. Packaged water brand Kinley grew by 14% and Maaza by 11%.

The morning after the Coke Studio party, Kent flew to Amritsar on a market visit. The city in Punjab has Coke’s highest per capita consumption in the country at 65 bottles a year. Replicating that kind of beverage guzzling in the rest of India will have Coke India opening plenty more happiness for Kent’s global vision.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required field are marked*