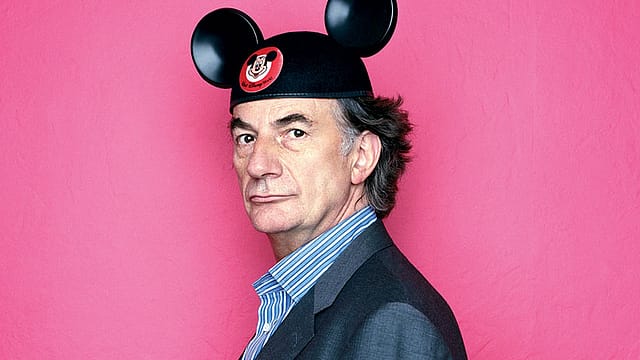

The measure of an icon

ADVERTISEMENT

SIR PAUL SMITH, the iconic British designer, has, over the past year or so, begun implementing a decision no one thought he ever would: He won’t do stripes anymore.

To understand how big that is, think of Louis Vuitton ditching the brown, monogrammed bag or Manolo Blahnik turning away from pencil heels. And yet for Smith, 69, it was easy. “I had to make up my mind, that’s all. There was no one to convince, no elaborate process.”

In any other business, even several times smaller than his ($684 million or Rs 4,100 crore in turnover last year), this would have been a long process since it may have impacted the bottom line. “But in my company it is just me. I decided, I did, simple,” Smith told me sitting at his fourth floor office on 20, Kean Street near London’s Covent Garden. While stripes have not been completely abandoned, they barely appear in the new collections, like say, the new handbags.

That Paul Smith (the company) is “just me” is perhaps an exaggeration: There are, for example, other shareholders. But the essence of it is true, that Paul Smith (the designer) has full freedom to do as he chooses. That doesn’t just make him a fascinating character in an industry stacked with standouts, but also arguably a great role model for Indian designers.

Smith, like the current crop of A-list Indian designers, is first generation. His beginnings were small: His first shop, when it opened in 1970 in Nottingham, had space barely enough for two people to stand. More important, he came from a nation where the idea of off-the-shelf branded designer clothing (as opposed to bespoke) was unfamiliar and there wasn’t even a supply chain for such a business.

Today, Smith’s stuff is sold in more than 2,000 stores across 73 countries, and he has succeeded in doing what India’s high fashion and luxury business folk have completely failed at—to create a global business and yet retain not just ownership, but also a distinct ethnic identity which is its trademark.

Unlike India’s designers, who all feed off the same, multi-million dollar marriage trousseau market, Paul Smith succeeded because he tried very hard at being different. Smith, unlike many other European design houses (Hermès, LVMH) never had any heritage to sell. Equally, he emerged on the scene when men’s fashion in Britain was still very “buttoned up. I loosened things up a fair bit,” he says.

Celebrated author Hanif Kureishi, a lifelong customer of Smith’s, has a historical perspective on why the designer has been able to pull this off. Kureishi says Smith’s attitude comes from being a product of the 1960s, when, he says, “barriers between things broke down in Britain. He comes from an age when many of the class issues began to collapse and so [he] brings together a mixture of glamour, punk, pop, and street culture, and does it with particular, nonchalant, wit.” Kureishi, who spots references in Smith’s work from The Beatles and Rolling Stones to David Bailey and Ray Davis, says, “Coming from a lower middle class, he [Smith] can also constantly laugh at the seriousness of high fashion: That’s what makes it work, and that’s what makes it so British.”

One approach to high luxury revolves around the idea of tradition, the belief that when craft moves down generations, its value increases. Paul Smith is the antithesis to that: At the core of his empire lies the idea of disruption (including disrupting his signature stripes) and everything, including choosing independence and freedom over scale, flows from that.

CONSIDER HIS AVERSION to debt. Smith says, “I don’t believe in debt. Anything I cannot immediately pay for, I believe I don’t need to do. I don’t like keeping things pending for the time I am able to pay.” Absence of leverage ultimately restricts size, but Smith doesn’t mind. “At every stage of my life, I have been happy with what I have had. This sounds very easy, but as a business it is very difficult to do when everyone is always telling you how you can sell and make billions.”

Perhaps a deeper reason for shunning debt is to avoid getting tied down to any business dogma, something that would ultimately curtail his freedom. That’s why, despite numerous, multilayered attempts at courtship to try and lure him into one of the big conglomerates of luxury—Kering (earlier PPR), LVMH Moët Hennessy-Louis Vuitton, etc.—he has steadfastly stayed single. “I never joined a conglomerate or brought in investment bankers to fund my growth. They won’t understand how I work,” he says, adding: “Bankers keep telling me how much more money I would make, but to me that has never been the point.”

Smith says he’s always been cautious about money for a few reasons. First, he doesn’t like sacking people. Attrition rates in his company have always been in single digits. “So, I don’t like taking risks that might in the future mean firings. Then, I have never seen the point of the kind of greed we have seen recently [leading up to the 2008 downturn]: Money for the sake of money has never been my game.”

Till a few years ago, all of Paul Smith Group Holdings, the parent company, was held by Smith, his wife Pauline, and John Morley, a long-time business advisor who also sits on its board. In 2007, Pauline and Morley sold their stakes, 25% and 15%, respectively, to Itochu, Paul Smith’s Japanese licensee, of over 30 years. Both wanted the money to help relatives. Smith retains majority control of 60%.(Among designers of comparable age, Smith and Giorgio Armani are similar: Both have aversion to debt, and both control their companies. Ralph Lauren is listed on the New York Stock Exchange.)

This allows Smith to do business his own, unique, perhaps even idiosyncratic way. In his home country Britain, he owns all the five flagship stores of the company and all the offices and warehouses. Brands like Smith rarely own real estate, preferring instead to focus on managing the label. The unattributed saying about Armani, for example, in the fashion trade is that he prefers to own and manage only the word Armani: Everything else is produced by strategic partners. At conservative assessment, Smith owns property worth more than $80 million in Britain.

Livia Firth, the influential sustainable fashion campaigner, says Smith was one of the first to understand the need for independence to campaign against ‘excess’, a term used in the industry that suggests over-the-top embellishment to feed runaway consumption. “He understood that if you want to be in control, you need to retain control. He has been able to, more than many other brands I know, keep a tight control of his supply chain and establish a very long relationship with his suppliers, precisely because of its independence.” She adds that Chopard, the biggest family-owned luxury jewellery brand in the world, and one of the brands she works with, has similar principles. “It is a pleasure to deal with designers and companies who walk the talk and are in charge of their own destiny,” says Firth. That Smith, on principle, does not use skins of such rare species as python or alligator, cheers her further.

In 2005, Smith had a brainwave that his Los Angeles store ought to be in the shape of a giant, shocking, pink shoe-box. The idea had come from a book, Casa Luis Barragan: Poetry of Colour. Smith thought pink would look stunning against the undiluted blue of the California sky. “This would be our flagship store in LA, on Melrose Avenue, which would look nothing like any other Paul Smith store. Now ask yourself, would I ever be able to sign off something like that in a jiffy if I was owned by a conglomerate?”.

After that store, showing zero consideration to standardisation and uniformity, twin shibboleths in the world of luxury, Smith’s next two major stores, in Seoul and Melbourne, again broke the mould. The one in Seoul looked like a spaceship, while the Melbourne one was housed in a heritage-listed Gothic building.

The independence has also meant that Smith has been able to notch up numerous tie-ups—rugs (with The Rug Company), designing superbikes with Triumph, creating a limited edition cover for D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover (Penguin Classics), adding colour to Leica cameras, tableware with Stelton, and sports jerseys for Manchester United and the bicycle race Giro d’Italia.

Dylan Jones, editor of the British GQ, and a long-time follower of Smith’s work, says that “Paul remains fresh and energetic because he has built his business exactly at the speed and temper that he wanted”.

BUT HOW DOES SUCH ECLECTICISM build a global empire that sells more than five million items, including 45,000 of his famed suits, a year?

Paul Smith’s items combine a sense of British laidback whimsy, a mood, an attitude, strips of colour that appear suddenly in his dark, sober suits, and so on. It is the pink lettering on the glass in the pink LA store which says ‘Please come in’. It is about his obsession with stripes, first with 28 colours, and then pared down to 14, which he put on clothes, socks, bottles of Evian water, skis, and even a BMW Mini. It also means that at a Paul Smith store, you might find everything from wall art to toys to carpets to suitcases, apart from the usual clothes and perfumes.

This shows up on the balance sheet where accessories brought in around 42% of sales in 2013, up from 40% in 2012. Managing director Ashley Long, who has been with the company for 23 years, says he got a call one morning from Smith saying he had asked their big new store on 9, Albemarle Street in London to put their umbrellas (black on the outside, with funky prints inside) in the shop window “because it looked like it might rain”. “At the end of the day I got another call from Paul. He said, ‘We sold seven umbrellas!’ That’s what makes him excited, and that’s the detail with which he tracks everything. He is a natural shopkeeper.”

Smith was one of the first designers to make a major push into Japan, signing his first licensing deal there as early as 1984 and launching the flagship store in Tokyo in 1991, even though the brand was already being sold in around 60 multibrand outlets in Japan. In a very rare example in fashion, the Paul Smith flagship in Tokyo opened before a similar store in Paris, which followed in two years.

This continues to serve him very well. Japan brought in 43% of revenues in 2013 and has 524 stores, around double the number in Britain.

If Smith spotted the Japan opportunity early, he was late to China. The flagship store opened in Beijing last year, and now the company is planning on opening around 25 stores. Paul Smith also recently opened in Panama and hopes it will be an entry point to South America. Stores have opened in Indonesia and the Philippines. A franchise is opening in South Africa.

Paul Smith has stores in New Delhi, Mumbai, Bangalore, and Kolkata, and plans to grow in other cities, especially as it readies to bring in its women’s lines to the country. It also quickly indigenised, with a Nehru collar jacket only sold in India, the only brand apart from Italy’s Canali to introduce this.

This push outside of the developed markets is now an imperative. Nearly 40% of sales come from Britain and Europe, and after doubling every five years for ages, the company grew just 1.2% last year. In other words, Paul Smith needs to diversify outside Europe. Other markets (see table), though small in the overall scheme of things, offer a glimmer of hope: In India, for example, between 2011 and last year, sales have more than doubled, from £104,789 to £228,311. The other area of hope: online sales, currently 4.5% of sales, growing 20% annually.

“There has been a drastic fall in the number of places where we can sell in Europe. We used to be in hundreds of stores. But in the last two years, we have seen store after store close,” says managing director Long. But Paul Smith is not taking it all lying down: One store has already come up at Mayfair, and two more are planned in London, at Heathrow Terminal 2, and Canary Wharf. In March 2015, a major store will open at the new World Trade Centre in New York, while a store has already opened in Hamburg, with Munich to follow.

THE SON OF A tradesman, at 16, Paul Smith was sent to work at a clothing warehouse in Nottingham, when all he wanted to do was become ace cyclist. At 17, a cycling accident left him with broken limbs, and a broken nose. The broken nose gave him a certain flair, but the accident put an end to the cycling dream. His girlfriend, then Pauline Denyer, had a degree in fashion from the Royal College of Arts, and together they started their first shop. Denyer moved on to pursue her passion in art but Smith stayed on in fashion. After several awards, including the Walpole British Luxury Award, the one-time cyclist with a broken nose is today Sir Paul—with a portrait that hangs at the National Gallery—firmly a member of British business aristocracy.

But the fame and money hasn’t changed him. “You won’t hear a bad word about Smith in London,” Kureishi told me. “He has remained a nice guy. He hasn’t disappeared into the global world of fashion. He is still around, accessible to all his friends. That charm seeps into his brand.” GQ’s Jones says that Smith is “essentially not greedy, which is a fantastic example in our business and in our world today”.

In London’s fashion circles, Smith has a reputation for treating his 1,000-odd employees with genuine concern. One of Smith’s employees at Keane Street recalled that when she joined a couple of years ago, Smith came by after a month or two and asked her how she was doing. The employee rattled off all the things she has been able to accomplish in an effort to impress the boss but Smith stopped her. He said, “No, not all that. But are you? Are you all right? Are you settling in?”

Characteristically, Smith likes telling stories of people who have been nice to him. In 1977, when he was looking for the first flagship store in London, he had zeroed in on 44, Floral Street, at Covent Garden. The man who owned the building wanted £35,000 for it. But Smith didn’t have £35,000. “Do you have £25,000?” he asked. “No,” said Smith. “Fine,” said Heath. “I like you; you seem like a nice chap, so you can pay me in instalments.” Smith paid him in instalments for eight years, with no real written deal between them. He describes the whole affair as “surreal”.

There is a surreal quality about him as well. His office is packed with hundreds of what can only be described as things. Everyday, scores of people from around the world send him all sorts of things because “it is well known that I am a keeper and not a thrower, I think inspiration can come from anywhere”, says Smith. There are cycles (of course), old TV sets, a box of vintage mobile phones, cameras of all shapes and sizes, photo stands, a football, a rugby ball, hundreds of books, train sets, toys (he loves rabbits, so there are a lot of toy rabbits), rubber chickens, and a perfect cut-to-scale model of his office made of paper and laser-cut metal.

Despite having built a fashion empire, Smith, who doubles as chairman and chief designer, has no declared succession plan because “I have no plans to go anywhere”. Ask him how he’d like to be remembered, and he’ll say, “As a jovial person”. When asked to design a sculpture for the 2012 London Olympics (with the studio Charming Baker) Smith made an aluminum and steel piece called Triumph In The Face Of Absurdity. At first look it’s a bicycle ridden by British gold medalist Chris Hoy, but a closer peep reveals that the whole sculpture of the cycle is held up by a tiny iron mouse at the base, Atlas style. This irreverence, described in the latest book on him, Hello, I am Paul Smith, is characteristic Smith.