THE DAY AFTER DIWALI 2010.BHOGAL MARKET, NEW DELHI. The city was still sluggishly trying to shrug off the effects of Diwali over-indulgence, and the otherwise packed market wore a deserted look. Inside the Nokia store, however, all was brisk efficiency. A fleet of large cars swept up and disgorged an army of suits. Stephen Elop, the CEO of Nokia, was on his first trip to India after taking over from Olli-Pekka Kallasvuo, and wanted a worm’s eye view of what was wrong with the company. Despite being the market leader globally, the mobile handset maker was not as profitable as it once was. Elop hoped that he would be able to find some clues in India, one of Nokia’s biggest markets.

Nokia India refused to comment on the visit, but company insiders, who asked not to be named, said that Elop (Nokia’s first non-Finnish CEO) was besieged with requests for dual SIM phones. Dealers, such as the one in Bhogal, drove home the fact that dual SIM models account for 35% of the Indian market for mobile phones, and Nokia was conspicuously absent in this segment. Elop returned to the Nokia headquarters in Espoo, Finland, and soon Nokia India was told it was to get a slew of dual SIM phones. Like any large manufacturing company, Nokia had a road map of what devices it would make and when. Dual SIM models were not on this road map; Elop insisted that Nokia bend the rules to keep an important market happy.

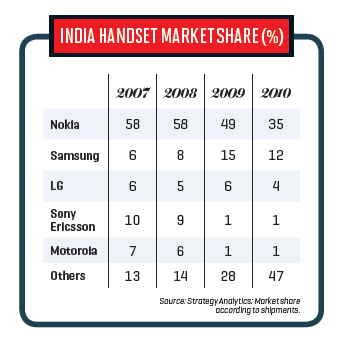

Nokia India’s brass see this as an indication of how serious the situation is—and how important India is to the global performance of Nokia. According to Strategy Analytics, Nokia’s share of the Indian handset market is 35.2%, and is the second largest contributor to global revenue. If this large market (with plenty of potential to grow in volume as well as value) begins to turn away from Nokia, the Finnish company could be in trouble. The signs are clear: Small, local players such as Micromax, Karbonn, Spice, and Lava are making bold forays into the territory Nokia once considered its fief—inexpensive feature phones (costing less than Rs 7,000 with basic functions such as internet access, music, and games). “When it entered the market, Nokia was a hit because the user interface and navigation was easy and addictive. It was good for non-tech savvy people. But now the same guys are looking for cool phones at cheaper rates,” says Anand Halve, co-founder, Chlorophyll, a Mumbai-based brand and communications consultancy.

Players such as Micromax are able to provide customers with “cool” phones. One of the reasons Nokia cannot fight back aggressively is its sheer size. With great size comes great bureaucracy, and while it might take less than a month for a local player to decide on a model, and source it from China, Nokia has to wait for clearances from headquarters, a process that can take over six months.

LITTLE WONDER THEN, that Elop went back to Finland demanding dual SIM phones for India. A few months after this came the now famous “burning platform” memo to all Nokia employees across the globe. In it, Elop wrote: “We’ve lost market share, we’ve lost mind share, and we’ve lost time.” Some former Nokia officials in India, who refused to be identified, say that Elop’s insights from India might have been added to the memo.

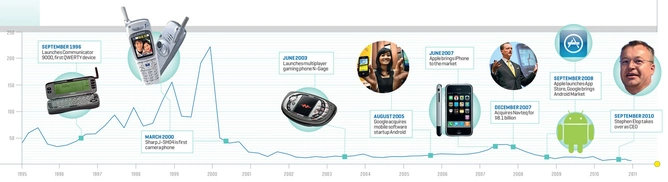

The memo, in which Elop compared Nokia to a man on a burning oil platform, forced to jump into an icy sea, has been widely criticised. But analysts who’ve been tracking Nokia say that he’s seen what insiders have closed their eyes to: the fact that Nokia has been the leader for too long and has grown too large to recognise and respond to the needs of an ever evolving market. It’s losing out to upstarts in its biggest markets. Nokia’s share price on the NYSE has plateaued since 2000—from $226 (Rs 10,100) in March 2006 to $8 in March 2011—while rivals such as Apple and Research In Motion (RIM) have grown from strength to strength. Many analysts say Nokia not picking up Palm (bought by HP) was a grave strategic error.

According to research firm Gartner, worldwide mobile device sales totalled 1.6 billion units in 2010, a 31.8% increase from 2009. Nokia is undoubtedly the market leader, but data from market research firm IDC show that its market share slipped from 36.9% in 2009 to 32.6% in 2010. Competitors such as Samsung, RIM, Apple, and LG are gaining incremental market share.

It’s happening in India as well, where Nokia’s market share has fallen from 49% in 2009 to 35% in 2010. Smaller players, such as Micromax and Spice, have made huge gains in the same period; the combined market share of the smaller players increased from 28% in 2009 to 47% in 2010. Team Nokia India is hoping that dual SIM phones will help reclaim some of the lost market share. The managing director of Nokia India, D. Shivakumar, brings the conversation back to the fact that the dual SIM phones would be game changers. Most of these phones—at least the early models—will be in the feature phone category. As in China, the Indian market is driven by sales of feature phones. Feature phones account for the lion’s share of the market but are not profitable; the margin on these handsets is just about 5%.

The problem for Nokia India is that even as its global CEO writes about burning platforms, the local management believes that there’s no fire and so no need for firefighting. “There seems to be a disconnect between ground realities in the local markets and how headquarters is reading them. The local management has been in denial mode about losing market share,” says a former Nokia executive. Asked about the importance of market share for Nokia India, all that Shivakumar says is: “For us, market share is absolutely critical. It is the only parameter to judge how competitive you are. If you are competitive and doing the right thing, your market share will increase.”

WHAT NOKIA INDIA FINDS MORE IMPORTANT is the fact that all the elements of the business, including production, are in India, and they can be leveraged to make the country a test bed for its new strategies. The R&D centre in Bangalore works on the user interface for all Nokia phones. But pride of place goes to Nokia’s factory in Sriperumbudur near Chennai, which has technologies, including hot soldering machines for LCD screens, that are not available at other plants. The factory itself is a hive of activity; conveyor belts bear the innards of phones past white-gloved workers, who swiftly fix components and accessories to the instruments. Some of them are so good at this, their hands are a blur. While the initial stages of production are almost completely automated, as the work gets more detailed, manual intervention increases and the production lines are so crowded with workers, it’s impossible to step through even to take a quick photograph.

A short distance from the factory is the storage warehouse where phones are packed for export to 70 countries or for the domestic market. Large enough to house two football fields, the warehouse is rarely silent. Phones bound for Africa need to be packed in steel containers, those headed for European markets go into wooden crates, while the domestic market gets cardboard boxes. The stock at the warehouse lasts for two days; at any given time, at least half a million phones are stacked here.

The Nokia India brass believe there’s plenty more room for growth. Apart from wooing new customers, the company is looking at retaining existing users who want to replace their phones with new models. “People like new phones and new features,” says Shivakumar. However, Nokia India’s biggest innovation in this segment was way back in 2003, when it introduced the 1100 model. It was a monochrome phone with a torch built in—a first for mobile handsets—as well as a dust-free keypad and anti-sweat grip. The market loved the phone and it became one of the bestsellers for the company.

According to the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India, there were over 771 million mobile phone users in India in January this year. Of these, 33.5% were from rural areas. In the last few years, mobile service operators have seen the majority of new subscribers coming from rural areas. According to analysts with research firms, Nokia mirrored this growth with over 60% of its sales coming from rural markets. The 1100 was created for this segment. But in eight years, customers have evolved and want more from their phones.

Nokia has been unable to create another blockbuster handset like the 1100, but it has not ignored its rural customer base. Its mobile services platform, Ovi, includes a segment called Life Tools, which costs users Rs 60 or so a month. Life Tools runs on all handsets, and offers locally relevant information to users. This includes the wholesale price of vegetables in nearby markets and weather updates for farmers, who form a significant part of Nokia’s customer base. According to Nokia data, nine million users in India, China, and Indonesia have signed up for Life Tools since December 2010. “Ovi has good services, but Nokia’s execution has left it cold. They have to evolve their market strategy in markets like India where they still command a strong user base,” says Melissa Chau, research manager (client devices), IDC (Asia/Pacific).

Nokia is trying to replicate the success of Life Tools with its new offering, Nokia Money, a service that will allow users to treat their mobile phone handsets as ATMs. The service runs across handsets and operating systems, and is targeted at rural users and those without credit cards (or even bank accounts).

“Nokia will continue to be the Maruti of the handset business and enjoy a leadership position in the market. There is no doubt that they are good in the sub-Rs 7,000 category,” says Chetan Nanda, managing director, StarMobitel, a Delhi-based mobile phone retailer.

THE QUESTION NOW BEING ASLED by analysts and industry watchers is whether Nokia will see any long-term gain from its focus on the feature phone segment. The volumes, while high, are not enough to compensate for the low price, low margin strategy. To really prepare for the years ahead, Nokia might do well to focus on the nascent smartphone segment in India. The share here stands at a lowly 4%. According to the U.K.-based research firm Canalys, the smartphone market in India stood at 6,322,970 units in 2010; this could reach 38,571,970 units by 2014.

Gartner numbers show that 19% of all handsets sold in the world are smartphones; in 2010, Nokia’s share of this market grew by 48% (year-on-year) according to IDC data. The margin on smartphones is typically between 12% and 15%. That’s for the handset alone; services such as application downloads generate more revenue. With a younger and more cash-rich generation of customers waiting in the wings, this market could boom in a few years.

“Hardware is not an issue and phones such as N8 and N7 are really good. It is the operating system and software where Nokia is faltering,” says Nanda. Asked to name the five top smartphones, he chose two Sony phones, and one each from Samsung, BlackBerry, and HTC. Nokia was not on his list.

Nanda is not alone in trashing Nokia’s operating system, Symbian. Elop did so: “Symbian is proving to be an increasingly difficult environment to meet the continuously expanding consumer requirements, leading to slow product development and also creating a disadvantage when we seek to take advantage of new hardware platforms.”

This public flaying of Symbian was followed by an announcement that Windows would replace Symbian as the operating system on Nokia phones, paving the way for the Windows phone (WP7), expected to be launched in 2012. One of the reasons for moving to Windows was to allow developers a free rein; Nokia is banking on there being more Windows app developers than Symbian. Given that it is the apps (and app store) that make a smartphone, it matters hugely that developers take to any new OS. Today, Forum Nokia has four million registered developers, 200,000 of whom are from India. They will team up with Microsoft developers, for PCs and mobiles, to create the much-needed ecosystem to counter Apple and Android.

“Earlier, mobile application development used to be niche and there used to be a longer learning curve. But the market is changing and now even the regular Java developer can adapt quickly,” says Shiva Bayyapunedi, CTO, Apalya, a company that develops mobile phone apps.

The poster child for app stores is, of course, Apple’s store, which has 314,644 iPhone applications (as of February 2011). The Android store has 185,000 apps, while Nokia’s Ovi Store, in comparison, has only 35,000 apps. What should have Nokia sitting up and taking notice is the fact that India alone accounts for 4.5 million downloads a week from the Ovi Store.

Today, because India is still a small market for smartphones, it does not get preferential treatment from the Nokia HQ for early launches or customising models for the country. But the nascent market could be ideal for Nokia. Unlike the U.S. or Japan, the smartphone market in India is not operator-driven, so Nokia can experiment with design and features. More important, Nokia can take advantage of the large community of app developers and techies in India to populate its app store. The Windows deal might also help attract more developers.

Apple does not see India as a serious market yet, so this might be Nokia’s chance to establish itself and take on players such as RIM and Samsung. There’s a lesson for Nokia and others in RIM’s success story. According to Strategy Analytics, BlackBerry sales grew 327% between 2009 and 2010 when the company introduced free messenger service and slashed prices. A BlackBerry sells for less than Rs 10,000 today. This was a smart move intended to attract the younger crowd, which wants features and style at a low price. While Nokia has not yet adopted this strategy for smartphones, small players such as Micromax are running with the idea. “The idea is to make a feature phone work as a smartphone and not get tied to the OS functionalities. Smartphones should shake off the image of being just for rich people,” says Arun Gupta, director, business development, MediaTek India Technology, a firm that supplies semiconductors and other components to handset makers.

Upgrading its existing India factory to make smartphones might help the company in the near term. But this seems unlikely to happen. “Let us give it time. We have the skill sets and we might have to develop some new capabilities,” says Shivakumar. Today, the factory exports almost half its output of feature phones to 70 countries. If Nokia is able to similarly flood the market with smartphones, it need not fear the loss of a few percentage points in market share.

But, as Jane Wang, Beijing-based senior analyst at Ovum, a research company, says: “Nokia’s smartphone strategy is not very clear. They have to come out and speak about it. They have to show their capabilities.”

Nokia also has to figure out a way to get customers to buy Symbian phones even after the announcement that the OS is no good. Some loyalists might hang on till the WP7 is launched in a year or so; others will move to Android or BlackBerry devices. If the company wants to make a mark, it has to develop something “magical”, says Prasanto Kumar Roy, president and chief editor, CyberMedia Publications.

Nokia India officials, however, say things are not so dire. The lifecycle of a Nokia phone is 15 months to 18 months, which means a customer will start looking for a new phone only after more than a year, and will be ready to upgrade when the WP7 is launched. But industry watchers are not as optimistic. “Indians have a penchant for free things and when BlackBerry messenger came for free, it took off in a big way. Nokia has been left behind due to the lack of a sexy phone,” says Halve.

The trouble for Nokia was that when it did try to take on BlackBerry’s messenger and mail client head on, it lost customers. Roy, for one, switched to a BlackBerry device despite having been a Nokia loyalist for over two decades. He says that it’s not the lack of handset options that irked him as much as the fact that Nokia stopped supporting BlackBerry mail clients on its phones and asked enterprises to shift to Ovi mail.

IF NOKIA MANAGES TO CRACK the twin problems of customer service and price in India, it can sweep the market. BlackBerry and HTC seem to have figured that out, judging by public perception of their phones—and the fact that sales of both have gone up in the past year. “Seven or eight years ago, Nokia set the standards in the market. It was then a brand to compete and beat. Now they have misread the market and have paid the price,” says Amitava Chattopadhyay, L’Oreal Chaired Professor of Marketing - Innovation and Creativity, Insead, Singapore.

Even as Nokia sorts out its act, Samsung appears to have got its strategy right. In India, the company has climbed to the second spot. Globally, Samsung’s market share is 20.2% (compared with Nokia’s 32.6%), but given that the company is seeing steady growth, while Nokia has been seeing steady erosion, it could overtake the leader in a few years. Samsung seems to have learnt from Nokia’s mistakes; its phones support multiple platforms (including its own Bada operating system). “We are on a mission to expand the high-end smartphone market. But the fact is that people want feature phones that look like smartphones and our R&D helps us to meet this demand,” says Ranjit Yadav, country head (mobile & IT business), Samsung India.

Even Motorola is trying to stage a comeback—this time as a niche player. The company is enhancing its retail presence, reviving relations with distributors and retail partners, and looking at tie-ups with operators. This strategy has borne fruit in India at least; Motorola shipped 0.3 million phones in 2010, compared with 0.2 million in 2009. That’s a drop in the ocean when compared with Nokia, which shipped 51 million phones in 2010. “The Indian smartphone user understands technology and its benefits. We believe this consumer makes choices based on preferred features and functionalities without compromising on quality and style. And, they are willing to pay a price for key features on the device,” says Faisal Siddiqui, country head (India), Motorola Mobility.

Similarly, LG has a cherry-picking strategy and will focus on 35 cities for its smartphone business. “These cities contribute 60% value,” says Vishal Chopra, business group head (mobile communications), LG Electronics India.

“Nokia has to come out with the right hardware, otherwise all its other efforts, including the Rs 500 crore ad and marketing budget, is of no use. They had a good smartphone, the Communicator, which they could not develop and convert into a cool product, as RIM did with BlackBerrys,” says Nirmalya Kumar, director, Centre for Marketing, London Business School.

Where BlackBerry scored was in recognising that the enterprise segment alone was not enough to keep it going. It invested in an ad campaign that made the brand seem cool and that drew in younger users. Thus far, Nokia appears to have lost connect with its younger users. “The variety of phones in its portfolio is not working anymore for Nokia. Its situation is similar to that of shoemaker Bata. Bata had something for everyone, but the moment specialist players such as Nike and Reebok entered the Indian market, it lost much of its sheen,” says Halve. Nokia too has something for everyone. It now needs to make everyone sit up and take notice.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required field are marked*