Forest rangers Inc.

ADVERTISEMENT

How do you conserve the world’s largest fish, killed by the hundred every year? How do you convince fishermen, for whom the whale shark is a prize catch, not to go after the endangered species?

This was the challenge faced by the Wildlife Trust of India (WTI) about a decade ago, when over 500 whale sharks were killed every year across the Gujarat coast. The fish migrated there all the way from Australia to give birth.

WTI, along with Tata Chemicals, launched a campaign to save the species. Religious guru Morari Bapu was also roped in to get the message across. He struck a chord when he compared killing the whale shark to a father killing his daughter, who, in tune with Gujarati tradition, had come home for childbirth.

The campaign was successful, even though back then Tata Chemicals’ participation was not driven by regulatory obligations. Until February 2014, animal welfare and biodiversity preservation didn’t figure on the list of CSR activities identified by the government as part of the Companies Act, 2013, which stipulates that companies devote at least 2% of their three-year average profit towards CSR activities.

January 2026

Netflix, which has been in India for a decade, has successfully struck a balance between high-class premium content and pricing that attracts a range of customers. Find out how the U.S. streaming giant evolved in India, plus an exclusive interview with CEO Ted Sarandos. Also read about the Best Investments for 2026, and how rising growth and easing inflation will come in handy for finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman as she prepares Budget 2026.

As part of its efforts to put conservation and biodiversity at the core of CSR, WTI has come up with Club Nature—a biannual, by-invitation-only gathering of corporate heads and government representatives to discuss how India Inc. can play an active role in this field. The nonprofit wants to kickstart a dialogue around CSR in wildlife and get the industry’s views on the issue.

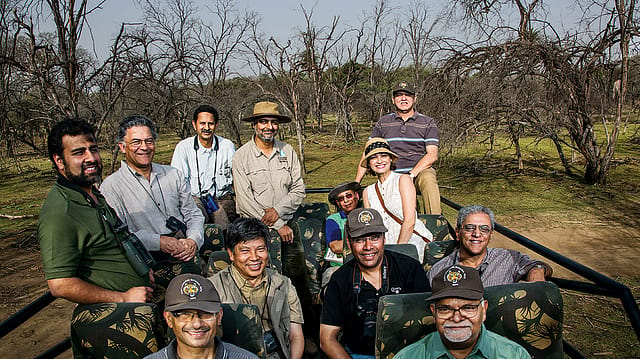

At the inaugural edition of Club Nature from May 1 to May 3, which Fortune India had exclusive access to, seven corporate heads and government representatives got together at Ranthambore National Park.

WTI founder Vivek Menon, who is also executive director and CEO of the organisation, kickstarted discussions with a talk on endangered species and how corporate money could help save them. After that, representatives from the companies and the government voiced their opinion about the problems they faced while taking up the cause and came up with a few solutions.

“In the eyes of the public, we [industry] are the culprits—we alter the landscape where we set up a business, a factory, or a power plant. [Through CSR,] the opportunity we have for doing good is huge,” says Vistara Airlines chairman Prasad Menon, who is also the chairman of WTI.

However, before a company decides to contribute to a conservation project, it has to understand the various stages in which funding progresses. Alka Talwar, corporate head, CSR, Tata Chemicals, says the first step is launching an awareness campaign. The next is engaging with the stakeholders—the fishermen, in the whale shark case—and making them understand the need to conserve. The third step is investing in scientific research to understand the habitat of the species. The last step is to chart out a road map to ensure that the species keeps thriving even after the project ends.

MARKING A SHIFT in the government’s approach, CSR in conservation is becoming a key channel to fund projects. “The government wants to involve NGOs, companies, and civic bodies in conservation,” says Bishan Singh Bonal, head of the National Tiger Conservation Authority. The move to seek funding from outside comes in the wake of a budgetary cut of 25% in the allocation for the Ministry of Environment, Forest, and Climate Change.

The ministry recently put up 14 endangered species for corporate sponsorship. The cost of conserving these species for the next five years is pegged at

Rs 400 crore. The funding sought for the great Indian bustard is Rs 104.5 crore and the Olive Ridley turtle is Rs 4.60 crore. While Power Grid Corporation of India and Gujarat Mineral Development Corporation are interested in saving the bustard, ONGC has offered to fund snow leopard conservation.

R. Mukundan, managing director, Tata Chemicals, says the distance between a company and the project site poses a challenge in selling the idea to shareholders. Nikhil Senapati, managing director, Rio Tinto India, concurs that most companies end up doing not CSR but “enlightened self-interest”. In other words, they only do CSR in a particular geography so that the company directly or indirectly benefits from it.

Vinayak Deshpande, managing director, Tata Projects, suggests exactly that—funding projects that complement a company’s business interests. (Think paper producers taking up afforestation.)

The lack of proper information on conservation is also an issue. “Often, the government and the NGOs are not in sync. Research highlighting the areas that need funding should be made available,” says Atul Kirloskar, executive chairman, Kirloskar Oil Engines.

“We all have different strengths. If a project is divided, each company can pick up the piece to which it can contribute best,” says Punit Lalbhai, executive director and sustainability champion, Arvind Ltd.

After a safari, which ended with the sighting of a tigress with three cubs, the group returned to brainstorming. Harish Bhat, member, Group Executive Council, Tata Group, asked, “Can there be a project [where all of us partner] that becomes a benchmark?” Everyone liked the idea, and that could well be the starting point.