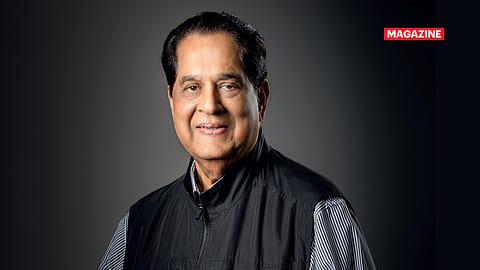

India’s Best CEOs 2025: K.V. Kamath, the Inspirational Institution Builder

LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT: There are leaders, there are institutions and then are those exemplars who are institutions of their own.

This story belongs to the Fortune India Magazine indias-best-ceos-november-2025 issue.

“IT WAS NOT CLEAR AT ALL. It was a tremendous turmoil.” That’s how Kundapur Vaman Kamath remembers the early ’90s — that phase of economic history when India’s financial architecture, then known as the development banking model, was dying a natural death. The institution he would soon lead, the Industrial Credit and Investment Corporation of India (ICICI), too, stood on the edge of irrelevance.

But there was somebody who was outlining the shape of things to come. That was Professor Coimbatore Krishnarao Prahalad. The-then professor of corporate strategy at the Stephen M. Ross School of Business in the University of Michigan would come to India each year to conduct workshops.

It was on one fateful day at a workshop in Bangalore (now called Bengaluru) in 1996 that Kamath, who had accompanied Narayanan Vaghul, chairman and managing director of ICICI, truly understood what the Prahalad-o-mania was all about.

Behind closed doors, 30 of India’s top business leaders were in rapt attention waiting to be dissected by an academic who saw a future before they did. “The workshop would crush you. Crush you in terms of what you’re not doing and what you need to do. But you came out that much stronger,” recalls the 77-year-old who is now the non-executive chairman of Jio Financial Services (JFS).

Later that day, Prahalad walked into the room and said, almost casually, “This session will be a little different. It won’t be about strategy, or what I usually talk about. It will be led by Professor Wayne Brockbank.”

Brockbank, Clinical Professor of Business at the Ross School of Business, introduced himself: “I have only three questions for you. After that, you guys will decide how the class goes.”

Akin to firing a loaded revolver, Brockbank shot off the questions.

More Stories from this Issue

“How volatile is your environment,” he asked. “Ten,” someone said. Everyone agreed.

“How competent are your people?” “Eight or nine,” came the consensus.

“That’s not bad,” replied Brockbank.

Before posing the third question, the professor told the motley crowd: “Think over this carefully.”

(INR CR)

Then as a bolt from the blue came a question that left the audience squirming: “How inclined is the organisation to change? How capable is your organisation? How capable of change are you as leaders?”

That loaded poser pierced through the animated audience. There was pin-drop silence. “People started thinking. I started thinking too. Anything I was trying to do in those first few months, the slope didn’t change,” recalls Kamath.

Soon, numbers began to float in the room: fives, sixes, sevens. Nobody went above seven. Kamath blurted out “four.” The crowd was stunned. And so was Vaghul.

With an almost fatherly squeeze of his protégé’s hand, Vaghul whispered: “In my opinion, we are seven or eight.” Kamath didn’t flinch. “Sir, that was the organisation you ran and not the one that is now going through change,” he replied.

That exchange — respectful yet brutal — not only marked a generational handover, but a transformation that the Indian financial sector was about to witness, led by a poster boy then, and an architect now.

“The professor then took us through what is change,” Kamath says. “How do you implement change, the need to drop baggage. That’s where the golden handshake came out. Technology came out. New businesses came out. We said we’re not going to do only project finance — we’ll do corporate lending; we’ll do other things. People laughed at us. But we acquired ITC Classic and Anagram, both in trouble. We had to learn, because we didn’t know retail. It was getting out of your comfort zone and doing things,” reflects Kamath, sitting out of JFS’s head office in the heart of Mumbai.

He pauses. “So, if it was a third person, apart from [S.S.] Nadkarni and Vaghul, who shaped me, it was C.K. Prahalad,” reminisces Kamath.

A LEAP OF FAITH

But to understand Kamath’s approach to change, one has to go back to Mangalore (now called Mangaluru), where a boy learnt about running enterprises the hard way.

His father, who served as the town’s mayor, also had a small roof-tile factory. Those years, he would later say, were a crucible of learning. “Right from my second year in engineering school till 1965 when I graduated, I ran the tile business,” Kamath recalls. “In a way, that was my first immersion into an SME. You learnt early what it meant to manage cash flow, meet payroll, and still have something left at the end of the day.”

It was at IIM Ahmedabad that Kamath’s life took a turn. One of his professors, B.G. Shah, quietly changed his life. “Give me your resume,” Shah said. “I’ll send it to I-C-I-C-I.” Kamath had no idea what the acronym meant. A few days later a call for an interview landed him in Bombay. He went, was hired, and walked into a world that would define him.

ICICI was then being run by a 600-odd team of executives. It was not glamorous, but it was serious. “They were all professionals. That sold me,” says Kamath.

Under his first mentor, S.S. Nadkarni (who headed ICICI then), he learnt the art of project appraisal. Under his second, N. Vaghul, he learnt how to take risk and grow the balance sheet. The duo not only went on to build an institution but a generation of leaders who would go on to give wings to India’s financial sector renaissance.

ICICI became a leadership factory, producing CEOs who would go on to run banks, insurance firms, brokerages, and non-banks of various hues. Notable among them were Renuka Ramnath, Shikha Sharma, Kalpana Morparia, Vedika Bhandarkar, Vishakha Mulye, Nachiket Mor, Kishor Chaukar, Ajay Srinivasan, and V. Vaidyanathan. [In fact, any omissions are purely coincidental.]

Not surprisingly, admiration for Kamath still endures.

As Shikha Sharma tells Fortune India, “Though he had a very strong reputation for intellect and delivery, and was one of the blue-eyed people of Mr Nadkarni, yet he gave you the space to have an alternative point of view. The problem with a lot of leaders is that they do not allow that alternative point of view, but Kamath did.”

In the early 1980s, Kamath was sent to London to study leasing. There he saw the future in a machine which could compute what had taken him hours with a calculator. When he returned, he searched Bombay for a similar machine, found a techie who introduced him to a then-exotic programme called SuperCalc, and also went on to realise the potential of what would one day be called a spreadsheet.

As Sharma remembers vividly: “Kamath is a great teacher and a great learner at the same time. It was he who sat me down and first taught me how to use the spreadsheet. He was an early adopter, and very happy to teach people around him.”

When Vaghul took over as chairman, Kamath computerised an entire office floor. Every desk had a machine, every secretary learnt WordPerfect.

Then came a detour for Kamath at the Asian Development Bank, Manila, then Jakarta, which gave him a helicopter view of rising Asia. But destiny had something else in store. In 1995, a call came. “Vaghul is coming to Singapore; he wants to meet you.” Over coffee, his old mentor said simply, “Next year, I retire. I want you to take over.” When Kamath returned to Bombay (now Mumbai) in 1996, the world had changed. The government guarantee that had kept development banks solvent had been withdrawn. The economy had opened. Customers were struggling; capital was scarce. “We had to reinvent ourselves,” says Kamath. That’s when the Prahalad episode led to a pivot that changed the course of history, and Kamath’s leadership trajectory.

THE MERGER

By 2002, ICICI was outgrowing itself. The parent institution was four times the size of its banking subsidiary but only the subsidiary had a banking licence. Logic and survival dictated what seemed impossible: a reverse merger. The risk was immense. No development finance institution (DFI) had ever morphed successfully into a commercial bank. But Kamath had already concluded that the DFI model was extinct. Retail banking was the new frontier and so the merger took place as the logic was simple: the banking licence is in the bank, and that was the only way it could raise resources.

Shikha Sharma, who was part of that transformation, remembers how Kamath pushed the boundaries of ambition: “When I was starting out in the retail funding business, we presented him a plan. He looked at it and said, ‘If this is all you want to do, let’s shut the business before we start.’ Then he gave us a target four or five times larger. It was terrifying but he didn’t punish us for falling short. It was about imagining the impossible, not fearing it.”

The merger came with surprisingly little resistance. Years of internal churn had inoculated ICICI against the fear of change. “People had internalised it,” says Kamath.

The early 2000s brought a confluence of fortune: the rise of India’s IT industry, the emergence of a salaried middle class, and a new appetite for credit. “That ecosystem of an aspirational India made retail possible,” Kamath says. Though there were missteps; credit scoring was primitive, defaults common. But Kamath believed the experiment was a step in the right direction. He admired the nimbleness of Wells Fargo and Capital One, and borrowed the principle that technology, not branches, would define Indian banking.

THE MAN, THE MACHINE

Kamath chose technology as his lever. He still remembers the weight of the five-pound mechanical calculators he had used at the start of his career and by the late 1990s he was teaching a whole institution to think digitally.

The first battle was cultural. “When we said we’d bring in ATMs,” he recalls, “everyone said customers would never use them.” Banks then measured scale by branch count; ICICI had 150. “At that rate, it would have taken us 200 years to match the largest bank. We had to think differently,” recalls Kamath.

He installed a thousand ATMs in one go. Within days, they were running 24 hours, each handling nearly 1,700 transactions.

As Sharma points out, “When it came to technology, Kamath was a very early adopter. A distinguishing feature of leaders who make a big impact is that they see ahead of others and are willing to bet on those moves much before anybody else.”

From there, innovation became a habit: machines replaced tellers for balance inquiries; branches ran from eight in the morning to eight at night in two shifts; efficiency became culture.

A young woman executive once proposed doing away with teller queues entirely: customers would fill envelopes with cash, drop them at any desk, and receive a stamped receipt. Counting would happen later, under camera. Kamath balked. “What if I put in 50,000 and you say 49?” he asked. She smiled. “Sir, you never stand in line.” It was a moment of humility. He began visiting branches across India, speaking directly with customers. Many told him, “Please increase the envelope limit. It’s so convenient.” The risk he had feared turned out to be a revolution in user experience. “Unless you experience the service, all talk of customer satisfaction is lip service,” reflects Kamath of the episode.

In Chennai, another young manager surprised him. Most branches took an hour to hand over after day’s end which was 8 p.m. She finished at 8:02 p.m. Her secret: start reconciliation at seven. “It was a simple yet brilliant productivity tool that made me realise that innovation happens when people feel empowered,” says Kamath.

Not surprising that the bank ran as an innovation laboratory where front-line employees designed solutions faster than committees could approve them. “It wasn’t top-driven, it was people-driven,” says Kamath.

THE LONG VIEW

When asked about India’s future, Kamath answers not as a banker but as a historian of growth. “Look at Japan, look at China. In 25 years, everything that needs to be built gets built: roads, ports, airports, cities. Inflation falls, interest rates fall, and currencies strengthen. Now it’s our turn,” he continues.

From his window in Mumbai, he watches the coastal road rise from the sea, the Atal Setu bridge arch across the bay: an apt metaphor for the country’s own acceleration. “We probably have 20 more years of building ahead. That’s the unfinished agenda,” says Kamath.

What’s next for the man who was conferred the Padma Bhushan, India’s third-highest civilian honour instituted by the government, as early as 2008? He smiles. “Nothing. I’m enjoying what I’m doing. As long as I see purpose, I’ll contribute.”

Despite his transition, those who worked with Kamath remember him for his gentle persona. “I’ve seen his daughter come into office, seen him talk to his wife. He is deeply family-oriented, very grounded,” says Sharma.

That humanist grace is what V. Vaidyanathan, CEO of IDFC First Bank, remembers of his first brush with Kamath at ICICI Bank where he led the retail business before venturing out on his own. “He was almost regal in approach… large-hearted and positive about the opportunity for consumer finance in India. I told him I knew the concepts and was raring to go. Maybe it struck a chord with him. His belief gave me belief.”

Years later, when Vaidyanathan got private equity major Warburg Pincus to buy into Future Capital Holdings in 2012, it was the biggest moment in his life. “When I told Kamath of the milestone, he did the unexpected: he took off his tie and gave it to me. I still have it. I rarely wear it, lest it fade.”

That quiet gesture captured something essential about Kamath’s leadership: his ability to inspire loyalty long after his organisational chapter had closed. For instance, Kamath proved to be instrumental in getting Hitesh Sethia as the CEO of JFS. Sethia, who was the first employee of ICICI Bank in Germany, had gone on to hold senior and country head positions in the U.K. and Hong Kong.

Sethia recalls a moment that revealed Kamath’s selflessness. After having stepped down as MD & CEO of ICICI Bank, Kamath was en route to the U.S. to visit his daughter. Sethia, then in Frankfurt, got to spend some time with Kamath during his stopover. “I asked him how long he’d be gone. He said six weeks.” The reply surprised Sethia as had never seen Kamath take a break for such an extended period.

Kamath’s reasoning was simple: he had to physically stay away and switch off, otherwise the incoming CEO would never get the space to grow. That stood out. It was a lesson Kamath himself had learnt from his own mentor. “When Mr Vaghul stepped down in May 1996 and I took over, he told me, ‘I’m going to the U.S. for three or four months. You look after it yourself’,” Kamath recalls. “That stayed with me. Once you hand over, don’t linger around. Don’t let people come to you to talk, positive or negative, about the new CEO. Be completely out of the picture. That’s what allows the next person to grow, and to grow fast,” says Kamath.

Even at JFS, he’s clear. “I’ll be available only when you want,” Sethia recalls Kamath telling him.

It is an answer that could come only from a man who has lived many purposes already: an engineer who ran an SME business, development banker, technologist, banker, and a mentor. Simply put: a once-in-a-generation leader who became an institution.