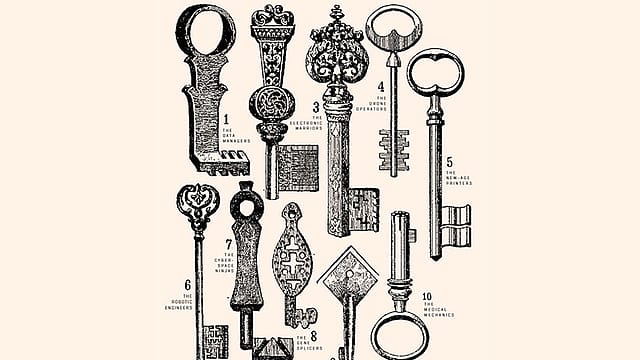

10 Jobs of the Future

ADVERTISEMENT

Automation and machines are taking over the world, and not just in some dystopian, post-Apocalyptic world that we see in the movies. Scientists, academics, and businesspeople have been pointing out for some time now that labour-intensive jobs are all going to machines, leaving humans at a loss. Jerry Michalski, founder of think-tank REX (Relationship Economy Expedition), was a little more dramatic during a recent interview to the Entrepreneur magazine. “Automation is Voldemort, the terrifying force nobody is willing to name,” he said, adding that it was the winner in the race for jobs. Reason: Humans have to be constantly paid for their work.

Machines, meanwhile, don’t have unions or productivity problems, and definitely don’t demand a salary. So a whole slew of old-world jobs—office and admin jobs, for instance, or sales and services, accounting, and most important, manufacturing—are going the machine way. And now there are digital brains that can perform surgeries, anaesthetise patients, write code, or even author books by churning data.

But it’s not all bad news for humans. Machines still have a problem with non-routine physical movements and abstract tasks such as visual and language recognition or interaction with people. David Autor, economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, says machines will not be able to handle jobs that call for “situational adaptability”—the ability to respond to unique and unexpected circumstances.

Autor says there will ultimately be only two ends of the job spectrum left to humans—low-skill, low-paying manual labour at one end, and top managers, scientists, and technocrats at the other. Both types of jobs will require original and creative thinking, adaptability, and the willingness to work collaboratively. Low-paying jobs such as caregiving or food service require interaction with people, as well as the ability to improvise rapidly. Again, people at the top will be required to work collaboratively and engage more with a diverse workforce, as global issues such as pollution or overpopulation are too complex to be tackled in isolation.

Over the next few pages, we look at “people” jobs that technology has created; jobs that machines will not take over. In short, jobs that Voldemort cannot snatch from us.

1. The Data Managers

The world needs a few million more managers who can make sense of big data.

It has been called the sexiest job of the 21st century by Harvard Business Review.

Shorn of the hype, data analytics is nothing but a technology tool that uses algorithms and visualisation techniques to capture and analyse huge amounts of data. Most companies are now trying to make sense of the massive data flow coming in from multiple sources in order to gain better business insights. But managing the sheer volume, variety, and velocity of data being generated every second requires no less than data wizards with a flair for statistical analysis, quantitative reasoning, predictive modelling, programming, and so on. Would that be enough? These skills sound a bit like those routine practices that could be automated in the near future. But those with sharp curiosity and the right amount of doggedness can still add value by burrowing through petabytes of data, spotting the trends, and making strategic recommendations based on them. How big is the market for these data translators? Consulting firm McKinsey estimates that India will need 2 lakh data scientists in the next few years. Globally the demand-supply gap is even wider. A McKinsey Global Institute study projects that the U.S. will face a shortage of about 190,000 data scientists by 2018 and further, a shortfall of 1.5 million managers and analysts who can understand and make decisions using Big Data.

2. The Space Invaders

Demand for satellite engineers is going up, but there’s little training available.

Machines seem to fit in naturally when one talks of space exploration; R2D2 more than Luke Skywalker, if you will. Of course, space mavens talk of the real need for space miners to extract elements such as neodymium from the Moon and Mars, and exobiologists to grow crops on space colonies. But the actual demands of the space industry are a little more mundane for the next five years or so. The demand is for satellite engineers, technologists, and space scientists.

While the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) has been regularly launching foreign satellites, there’s a new game in town with the growth of domestic private players building satellites. “Tiny modular satellites called CubeSats weighing 1 kg to 4 kg and costing under $100,000 (Rs 63.2 lakh) have revolutionised the way space products and services are delivered to end users,” says Narayan Prasad, co-founder, Dhruva Space.

Companies like his, making nano and microsatellites, have found willing financers in Google, Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic, and Qualcomm. A recent study by Northern Sky Research estimates that more than 1,800 satellites over

50 kg will be ordered and launched in the next decade, creating a $300 billion market. In addition, ISRO plans to launch 58 space missions by 2017.

The trouble is finding talent; India has exactly one top-grade school for space sciences, the Indian Institute of Space Science and Technology, set up by ISRO in Kerala.

3. The Electronic Warriors

Defence electronics engineers will be in demand, but supply will be very short.

The global defence electronics market is estimated to grow from $107.8 billion in 2008 to nearly $137 billion by 2022. In India, the strategic electronics industry is likely to touch $76.5 billion in the next decade. The opportunities in this sector are varied, ranging from standalone electronic systems such as tactical communication and battle management (worth around $18.5 billion) to major defence programmes including infantry combat vehicles, conventional submarines, frigates, and aircraft carriers (worth another $58 billion), per a recent report by strategy consultants Roland Berger.

The majority of these contracts will go to public sector defence units, ordnance factories, and the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO), but the private sector now wants in.

Job opportunities lie in specialised knowledge of designing, prototyping, and testing of systems for avionics, military communication, and electronic warfare. K.D. Nayak, director (R&D) at DRDO, says engineering graduates need to be trained for at least a year before they can start working. (Only DRDO and Bharat Electronics Ltd or BEL provide hands-

on training.)

There’s a critical need to develop a talent pool and involve institutions like the IITs, NITs, and IIMs to offer specialised courses in defence electronics.

“The idea is to create more awareness of defence in general and defence electronics in particular as a career opportunity, and also to fill the gap in the industry,” says Rahul Gangal, partner at Roland Berger.

4. The Drone Operators

The market is set to open up to commercial operators, but a dearth of qualified engineers could ground it.

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), commonly known as drones, made their first appearance in the early 1990s for surveillance and reconnaissance. By adding cameras, lights, audio sensors, or even a robotic arm, the utility of drones can be increased exponentially. That’s why, increasingly, drones are being used in the civilian space—for agriculture, infrastructure management, conservation, disaster management, aerial photography, or product delivery.

In India, however, drones are still primarily used for defence and law enforcement. But the Directorate General of Civil Aviation may soon allow commercial use of drones, which will open up this space.

Already, private players are into drone manufacturing. Bengaluru-based Dynamatic Technologies, for instance, is co-developing a lightweight unmanned aerial system with AeroVironment of the U.S., under the U.S.-India Defense Technology and Trade Initiative.

The local drone market may reach $421 million by 2021, according to 6Wresearch, a research and consulting firm focussed on emerging markets. Getting together a skilled workforce won’t be easy, though. To become drone experts, engineers will need training in UAV design, sensor development, vehicle communication, and vehicle navigation. As of now, India doesn’t offer such courses outside of government-run defence units such as DRDO and BEL.

5. The New-age Printers

3D printing could change manufacturing forever, and all it needs are hardware engineers.

While its impact is revolutionary, the technology behind 3D printing is straightforward—it works by placing individual layers of materials on top of one another until they create the desired object. By enabling a machine to produce objects of any shape, on the spot, 3D or additive printing is on the cusp of disrupting traditional manufacturing.

As its applications expand—from rapid prototyping to customised product development—and printer prices drop, new opportunities will open up. In fact, 3D printing has already gone beyond consumer goods and medical devices, and entered areas such as aerospace, building fixtures, and infrastructure projects. That’s not surprising as it ensures short production runs while mass customisation calls for software tweaking instead of expensive retooling.

The market is exploding. According to a 2014 report by industry analyst Wohlers Associates, the worldwide 3D printing industry is expected to grow from $3 billion in 2013 to almost $13 billion by 2018 and exceed $21 billion by 2020.

The technology is yet to pick up in India, given the huge cost of importing such printers. A few private players such as KCbots and LBD Makers are making 3D printers locally. Needed: hardware engineers with exposure to computer-aided design.

6. The Robotic Engineers

The market in india is still in its infancy, but the talent pool is good.

The robots are coming. Technology research and advisory firm Gartner predicts that more than 30% of all jobs will be replaced by robots and smart machines by 2025, and Ray Kurzweil, director of engineering at Google, anticipates that human thinking will become hybrid (biological and artificial intelligence) by the 2030s.

Already, machines have taken over repetitive jobs or hazardous missions like ‘manning’ space shuttles and defence carriers, and monitoring nuclear plants. Globally, the market for industrial robotics is likely to touch $46 billion by 2020, according to TechSci Research, a global consultancy firm.

India is not yet ready for the robot invasion, largely due to high adoption costs. A handful of startups like Pulkit Gaur’s Gridbots Technologies are already developing smart robots. Gridbots’s robots are being used to set up and commission nuclear plants for Bhabha Atomic Research Centre. “We are also in the process of developing bomb disposal robots. Those should be out by the end of the year,” says Gaur.

Despite the nascent market, the talent pool is good. Most of the robotics engineers are from premier institutions such as MIT, Harvard, and Stanford, or from home-grown ones, including The Centre for Mechatronics at IIT Kanpur or Jadavpur University in Kolkata. But in order to develop the right workforce for intelligent automation and robotics, ample specialisation opportunities in areas such as computer-integrated manufacturing, computational geometry, and artificial intelligence will be required.

7. The Cyberspace Ninjas

Prevention of data theft is just one of their jobs.

With the amount of cybercrime going around, there’s actually a job these days for data hostage specialists. It’s essentially a data manager, who specialises in ensuring that a company or person’s data is not held hostage by a cybercriminal. Up next: data-hostage negotiators, data-retrieval specialists, and damage-control analysts.

Unlike traditional security threats, the growing interconnectivity between people, devices, and organisations has opened up a whole new set of vulnerabilities, resulting in data theft and worse. With so much interconnectivity, a single vulnerable device could lead to a large-scale data breach. And therefore, the need for data hostage specialists.

According to a study by analytics firm Burning Glass Technologies, demand for cybersecurity professionals is growing 12 times faster than the overall job market and more than three times faster than IT jobs in the U.S. And guess what? One in every four millennials is keen to pursue a career in cybersecurity. India will need at least 1 million cybersecurity professionals by 2020, says IT industry body Nasscom.

This will include cybersecurity expertise in smart city projects, as well as Digital India, which plans to transform India into a digitally empowered society and a knowledge economy.

8. The Gene Splicers

India has miles to go before it can take part in high-end genomics research.

Genetically modified crops draw flak across the globe, but what price modifying humans? A genome-editing technology called Crispr (short for “clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats”) is reported to have the potential to change the genetic make-up of human embryos.

That’s good news for medical science, as DNA can be manipulated at a very early stage in order to deal with birth defects and genetic diseases. The ethical implications are another debate altogether, especially as news came out that a team of scientists, headed by Junjiu Huang (researcher at Sun Yat-Sen University), had experimented on human embryos.

Once the ethical lines are clearly drawn, gene modification could be a force for good. Unfortunately, India is still on the sidelines of genetics research. Only a few universities offer post-graduate programmes in molecular and human genetics. Though there are more courses in biotechnology and biochemical engineering, high-end research on genomics may still take years to flourish.

9. The Green Warriors

India’s big push towards clean energy is changing the job market.

Clean energy is one of the buzz phrases of this government, and it is pushing for alternative sources of power, including wind and solar. And that means huge demand for specialists who can innovate, advise governments on green strategies, and ensure compliance across industries. In practical terms, it calls for environmental scientists, sustainability officers, materials engineers, green energy technicians, and the like.

The government has upped its target for grid-connected solar energy, from 20 GW to 100 GW by 2022, and aims to produce 60 MW of wind energy, up from the current 22.4 GW. Plans are afoot to set up the country’s maiden geothermal power plant, generating 1,000 MW.

All these could lead to millions of new jobs, according to a report by National Resource Defence Council and the Council on Energy, Environment and Water. For instance, India could generate one million jobs if it reaches its solar power target and another 1,83,500 could come from wind projects (the numbers don’t include industrial manufacturing jobs).

The job market may get a boost with private players like SunEdison, ACME Cleantech, Welspun, and Hindustan Power getting into solar power. Japan’s SoftBank, along with Bharti Enterprises and Taiwan’s Foxconn, plans to invest about $20 billion in the country’s solar projects.

10. The Medical Mechanics

With a little government help, this could be the next big thing.

There's a $50 billion opportunity just waiting to be tapped. India has the potential to become a low-cost manufacturing hub for medical devices, ranging from X-ray machines to CT scanners to stents, in the next 10 years.

A study by Boston Consulting Group and the Confederation of Indian Industries says that the target is achievable, citing the fast-growing domestic market worth $30 billion, comprising public and private hospitals, diagnostic labs, and other health-care units. However, most of these organisations are now import-dependent (more than 70% of the medical equipment in use is not made in India), largely due to an inverted duty structure—tax for raw materials could be as high as 27% in this space while imported devices are taxed at 15%.

This explains the stunted growth in component/device manufacturing. Add to that the lack of industry-specific training. “Courses that feature medical technology fundamentals, which create the base for innovations, are few in India today,” the study says.

In a bid to boost the country’s medical device industry, the government is planning to set up an autonomous National Medical Device Authority that will promote local industry, create jobs, and ensure safety standards.