Master plan to reform public sector banks

ADVERTISEMENT

At first look,it seems like a classic case of slamming the stable door shut long after the horse has bolted, but since it’s government we are talking about, every little thing helps. Which is why an ambitious plan to recapitalise public sector banks and “future-proof” them is not just something to criticise. It may have some effect on the long-term financial health of these institutions.

The Nirav Modi Ponzi-like scheme, which has so far cost Punjab National Bank some Rs 13,000 crore, is having all kinds of repercussions on the banking sector. While private bankers are now being called upon by the Serious Fraud Investigation Office under the Ministry of Corporate Affairs, it is the public sector banks that have taken most of the flak.

There’s been some knee-jerk reaction in the form of scrapping the system of letters of undertaking (LoU) and letters of comfort (LoC), instruments that were used to great effect by Modi and others. Meanwhile, the government has asked all public sector banks to examine bad loans of Rs 50 crore and above for possible fraud, and has instructed them to seek the help of investigative agencies in case any fraud comes to light.

January 2026

Netflix, which has been in India for a decade, has successfully struck a balance between high-class premium content and pricing that attracts a range of customers. Find out how the U.S. streaming giant evolved in India, plus an exclusive interview with CEO Ted Sarandos. Also read about the Best Investments for 2026, and how rising growth and easing inflation will come in handy for finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman as she prepares Budget 2026.

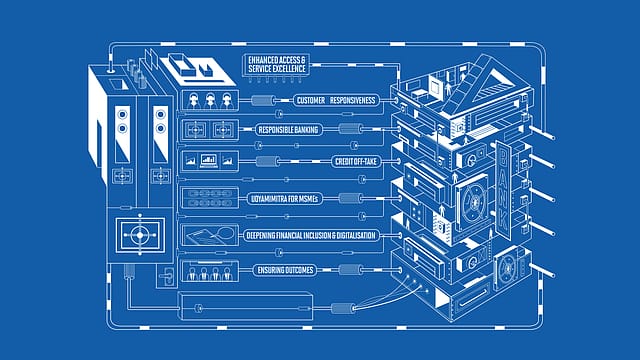

At the same time, the government is trying to put in place a long-term sustainable plan that will keep banks healthy. And no, the answer is not privatisation. Or at least, not yet. The answer, at this point, is in a 12-page booklet brought out by the Finance Ministry in consultation with whole-time directors of public sector banks. Released in January, the booklet details the government’s recapitalisation scheme for public sector banks, and also proposes a strong reforms package with 30 action points.

“It is all about future-proofing the banking sector and making it more responsive to the needs of the common man,” says Rajiv Kumar, secretary, department of financial services. If the various recommendations enumerated in the booklet are actually implemented by the banks, Kumar says the possibility of frauds and scams will be dramatically minimised if not completely rooted out.

The aim of the document is to completely revamp the functioning of the banks by plugging every loophole in the system so that no one—from junior to top banking officials, from external to internal auditors, from board members to various committees—either singly or in collusion with others can game the system.

That seems like a tall order, but it’s something that needs to be done. Public sector banks account for some 70% of banking in the country—and for a good chunk of the non-performing assets or NPAs. According to RBI data, NPAs in these banks reached Rs 7,33,137 crore in June 2017. Worse, PSU banks reported loan frauds of Rs 61,260 crore over the last five years. And that was before Nirav Modi.

The recommendations seem to cover most aspects of banking, or at least of loan disbursal, starting from how projects are appraised and approved. The government recommends hawk-like vigilance, and suggests that banks take steps to recover their money at the slightest hint of a default. It also tries to fix the responsibility of every member, including the MD, CEO, and executive directors, as well as those of the auditors—external and internal— and the bank’s audit committee.

A senior finance ministry official, who asks to remain anonymous, says these recommendations will tighten the screws on “nearly 40 corporate offices of the 21 public sector banks, because it is in these offices that all high-value loan proposals are scrutinised”. He blames these ivory-tower managers for the extent of NPAs, adding that the opportunity for fraud increases manifold because both disbursement and monitoring of loans are in the hands of the same managers.

Banks have been directed to set up Agencies for Specialised Monitoring to oversee credit exposures of Rs 250 crore and above and those that require domain expertise. These agencies are supposed to keep an eagle eye on the progress of every loan, and report to the bank’s board at the slightest hint of trouble. In case loans under these agencies do go bad, recovery will have to be through a specialised asset management vertical. And, as an incentive to officials tasked with the recovery, banks have been asked to link their pay with the amounts recovered.

Another significant recommendation is on consortium lending. Smaller banks, such as Dena Bank or Corporation Bank, join a consortium that funds large projects. These banks do not necessarily have the economic or technical expertise to get involved in such projects, but piggyback on larger banks such as State Bank of India. The idea is to make profits, but if the project hits a block, the smaller bank takes a hit larger than it can afford.

That’s why the government has now recommended that every member of a lending consortium have at least a 10% stake in the project being funded. More important, the government suggests smaller banks have a limited exposure to corporate lending. Kumar says the smaller banks can focus on small-ticket loans as well as on retail banking.

The large banks have not been let off the hook. They have been directed to adopt a standard operating procedure to determine the methodology used when approving a loan. By standardising this, the government hopes to remove the power of any one bank in a consortium to take decisions.

There are many other recommendations in the booklet, including on selection and functioning of auditors, and appointment of a risk officer. The big question is if all this is too little, too late. Would steps like these have prevented a Nirav Modi like situation from taking place?

Abizer Diwanji, partner and national leader, financial services, EY, has a different view. “The whole focus of the government,” he says dismissively, “seems to be on pinning blame on others rather than finding a solution”. But even he admits that the blueprint set out in the booklet “is an honest and sincere attempt to revamp the public sector banks”. It may not, however, be moving in the right direction. “The real test of this document lies in its implementation,” he says.

Ashvin Parekh, managing director, Ashvin Parekh Advisory Services, a global management consulting firm, is equally circumspect. He says these recommendations are not “the magic wand that will change the banking scenario” because there are too many problems left unresolved. His main issue is with the powers given (or not given) to the central bank. “The jurisdiction of the RBI is more constrained than anywhere else in the world,” he says, explaining that this is because if the RBI penalises a public sector bank, it is the government that will have to pay. So, the RBI is simply not allowed to levy a penalty.

Many experts agree. They say the banking sector has always had enough rules or laws, but the rot continued due to their poor implementation. There was the Board for Industrial and Financial Reconstruction (1987), the Company Law Board (1991), the Sick Industrial Companies (Special Provisions) Act 1985, the corporate debt recovery mechanism (2001), the master circular on wilful defaulters (July 2015) but they all achieved little because the political will was missing .

Ultimately, it’s more about insulating the banks from government interference. As long as a finance ministry nominee sits on the board of PSU banks, it is highly unlikely these banks will have a free run. But that’s a big ask. The government sees PSU banks as its tools for jobs like Aadhaar enrolling, distribution of social financial schemes, and the like. Letting these banks run free, without government supervision, will do the banks no end of good, but will definitely not serve political interests. And that seems to be the tale of Indian public sector reforms.

( The article was originally published in the April 2018 issue of the magazine. )