Blockchain comes of age

ADVERTISEMENT

IN DECEMBER, followers of the virtual currency (or crypto currency) bitcoin were shaken up by revelations that Craig Wright, a little-known Australian computer scientist, is really Satoshi Nakamoto, bitcoin’s mysterious inventor. Wright kept mum, only to corroborate the claims last month—even as observers like The Economist say he has to pass through a rigorous “paternity test” to prove he is legit.

It’s a fitting story, since establishing its legitimacy has been bitcoin’s biggest challenge in its short life so far (“Nakamoto” coined the term in a research paper published in 2008). First, it is not legal tender, and second, it is the currency of choice (along with other digital dosh) of narco traffickers, money launderers, and ransomware attackers, prompting a number of countries from China to Bangladesh to ban it. In India, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) hasn’t banned creating and trading in bitcoin as a commodity, but alerts the public that it constitutes an “unregulated grey area”. The shadowy reputation isn’t stopping mainstream businesses across the globe from exploring the technology underlying bitcoin—the blockchain. The main draw: lower transaction costs and direct connectivity between transacting parties without compromising security.

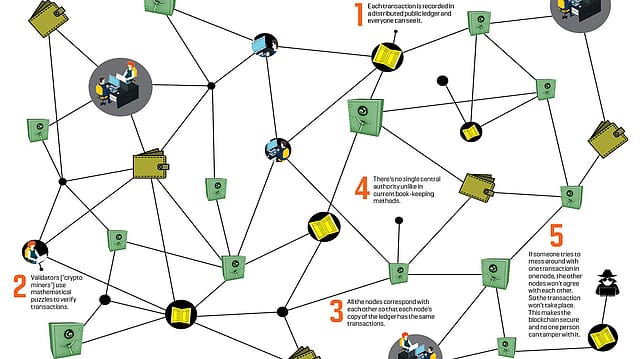

Simply put, blockchain is a network of computers that verify and approve transactions, which are then recorded on a distributed public ledger. Anyone on the network can see what transactions have occurred (changing record history is prohibitively difficult), although transaction details can’t be viewed unless one holds private keys to that data. Think of it as a secure but decentralised book-keeping system—there’s no central database of transactions, no custodian of data, no trusted third party like government, bank, or clearinghouse to validate transactions.

January 2026

Netflix, which has been in India for a decade, has successfully struck a balance between high-class premium content and pricing that attracts a range of customers. Find out how the U.S. streaming giant evolved in India, plus an exclusive interview with CEO Ted Sarandos. Also read about the Best Investments for 2026, and how rising growth and easing inflation will come in handy for finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman as she prepares Budget 2026.

For a better grasp of things, imagine a group of accountants working in a public square. Each has their own workstation and a copy of the ledger of transactions. Anyone in the square can have a look at these records. Whenever people in the public square transact with each other—say one sells the other a Rs 10 ice cream—they tell the nearest accountant. Hundreds of such transactions occur simultaneously; the accountant gets records of these bundled together, like a ‘block’ of transactions (which makes a blockchain unit). To secure a block, the accountant runs its data through a set of mathematical formulae that throw up a random string of numbers and letters, called a ‘hash’. The accountant records this string with the block, like a seal approving all the transactions recorded in it. The first accountant to crack and verify a block alerts all the others right away. If all the other accountants also record that Rs 10 sale at the same time, the group considers the sale valid and recorded. Meanwhile, onlookers can check the record in any ledger nearest to them.

Blockchain ‘nodes’ or computers act like these accountants—unless all of them verify a transaction simultaneously, it cannot go through. This makes it impossible to fake a transaction in the blockchain network, while the hash keeps information private.

Blockchain is also cost effective. A Financial Times report indicates that wider adoption of the technology could help shave off $20 billion (Rs 1.3 lakh crore) in costs associated with cross-border payments or self-enforcing contracts in bond or equity trades.

Even the RBI, in its latest Financial Stability Report, says blockchain can bring about a major transformation in the financial markets, starting with identifying collaterals (such as land records) and setting up payment systems. Mohit Kalra, chief executive of Delhi-based bitcoin startup Coinsecure, had met RBI governor Raghuram Rajan to discuss possible applications of blockchain. He says the central bank is responding positively to the technology. When a significant number of banks set up private blockchains, the RBI could ask all to operate on a national public blockchain, Kalra adds.

ICICI, INDIA’S LARGEST private lender, says it’s serious about blockchain solutions. “We are looking at using this technology for certain transactions … to make them safer, simpler, and faster,” executive director Rajiv Sabharwal said at the ICICI Appathon in April. “The banking system needs to work together to decide how to use this technology across the financial system.”

Infosys, India’s second-largest IT exporter and the creator of the banking solutions suite Finacle that is used by clients in 84 countries, recently announced a blockchain framework at its global client summit in San Francisco. “Several of the world’s leading financial institutions are already collaborating with us to build blockchain-powered banking applications and networks,” says Andy Dey, president, customer and operations, at Infosys EdgeVerve, a startup within the company mandated with such innovations.

Rajashekara V. Maiya, head of financial product strategy at EdgeVerve, says the company has factored in resistance from conservative bankers. “Banks are so sensitive about transaction data that they wouldn’t like to be on a public ledger from day one. That’s why we’ve developed a permissioned ledger that only gives access to a few banks,” he says. “It leverages the benefits of blockchain’s decentralisation, but doesn’t allow complete public access.”

India’s remittances industry could be a big opportunity for blockchain, says Brock Pierce, chairman of the bitcoin advocacy body Bitcoin Foundation, whom I met on the sidelines of a tech conference in Mumbai. Valued at an estimated $72 billion in 2015 per World Bank, India is the world’s largest remittance market, and Pierce believes blockchain could transform the market as it is the fastest, cheapest, most secure way of transferring money.

“Most of the growth will occur when people start using the technology without knowing it,” Pierce says, responding to the fear of using a hard-to-define system, let alone one that is associated with the tainted bitcoin. (He also assures me that bitcoin is no longer the hero of the story, though if VC interest is any measure, it is still way ahead of blockchain [see graphic]). Pierce has invested in the remittance service provider Abra that seems to encourage adoption by playing down this connection. Nowhere in Abra’s presentation or app will you see any mention

of bitcoin.

Pierce adds that for a large population of Indians working abroad, the cost of remittance through conventional channels could make an alternative like blockchain attractive. International wire transfer is the easiest way to remit money to and from India, but one has to cough up 14.5% service tax plus any charges levied by the remitting bank, and crediting the money to the beneficiary account may take up to three days. For domestic remittances, online transfers via National Electronic Funds Transfer (NEFT), Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS), and Immediate Payment Service (IMPS), a mobile-based 24/7 transfer facility) are low-cost options, but one has to still pay 14.5% tax for NEFT and IMPS transfers and RTGS transactions over Rs 2 lakh. Plus there’s a cap of Rs 10 lakh for NEFT and RTGS and Rs 2 lakh for IMPS.

Mobile remittance is growing in popularity but has its own limitations. For instance, a single transfer via Airtel Money can’t be more than Rs 5,000 and costs Rs 70. Sending money from a mobile wallet like Paytm to a bank account attracts a 4% fee, subject to a maximum transfer of Rs 5,000 a day and Rs 25,000 a month.

Compare this with the services provided by the blockchain-based remittance company Uphold. Headquartered in California, Uphold’s cloud-based financial platform enables users to send money instantly anywhere in the world and offers a choice of 14 currencies. Transactions are free for verified users while anonymous guests pay 0.45% to 1.95% of the transaction value depending on the currency.

The company also runs a proprietary distributed public ledger called Reservechain, which is “RBI compliant” (read: no cryptocurrencies involved), says Uphold’s India head Jayaraj Mehta. Uphold sent me $1 via its app to help understand how the system works. I received it within seconds and didn’t have to pay any fee.

Uphold has tied up with IDFC Bank and Yes Bank for payments and remittances, but neither bank would comment on it. “IDFC’s goal is to see that everyone, including people in rural areas with less access to banks, is able to transact easily [using digital tools],” says a spokesperson.

Another area that may grow is private blockchains. Large corporations prefer to transfer data with the help of bitcoin-like ‘tokens’ programmed to store information. Kalra of Coinsecure says companies like Louis Vuitton are considering fully controlled private blockchains for provenance tracking across the supply chain. “They (Louis Vuitton) wanted us to create a small chip alongside a private blockchain,” he recalls. The chip was to be placed in every Louis Vuitton bag in order to ensure better tracking. A QR code unique to each bag was to be transmitted via the private blockchain, so that a Louis Vuitton unit could authenticate every product. Coinsecure, however, turned down the project as it didn’t have adequate resources.

GLOBALLY, THE endgame for blockchain enthusiasts is a financial system that is integrated and decentralised. Pierce of Bitcoin Foundation talks about Ripple, another cryptocurrency, whose creators are trying to use it to connect international banks. “They are attempting to build an inter-bank settlement system, [which can bypass the need to] run through all the 10 or 20 clearing banks of the world. That will create much more efficiency for everybody. Ripple’s got hundreds of banks on board,” he says.

Though Fortune India could not independently verify Pierce’s claim, nine of the world’s biggest banks did join hands last year to set up R3, a New York-based consortium that develops and tests blockchain solu-tions for global financial systems. Today, it has 45 paying members, including Goldman Sachs, J.P. Morgan, Barclays, Bank of America, UBS, BNP Paribas, and Deutsche Bank. R3 is now testing its own distributed ledger Corda, built like a blockchain, and is developing solutions to enhance interoperability.

But we needn’t read too much in to the bevy of big names, cautions Rajesh Kandaswamy, banking research director at research firm Gartner. “There has been a recent rise in interest among banks, but it’s still tentative. [R3] may see big players getting together, but they’re not necessarily doing big things,” he says.

Pierce remains sanguine. “Just like telecom companies changed the technology by switching from copper wires to VoIP, large banks will evolve and change their infrastructure,” he says. “The financial system will definitely be democratised, but most of it will be co-opted by the incumbents, the large financial companies.”