CNG faced similar doubts at launch: GEMA president on row over ethanol-blended petrol

Apart from conserving foreign exchange reserves, the government’s ethanol-blending programme offers opportunities for rural development and rural employment, says the president of GEMA.

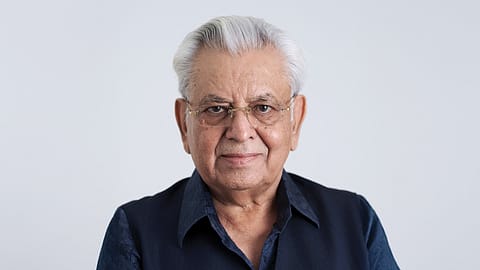

Amid the furore and angst over ethanol-blended petrol hampering fuel efficiency and the longevity of vehicles, C.K. Jain, president of the Grain Ethanol Manufacturers Association (GEMA), and founder-chairman, Gulshan Polyols, has argued that whenever a new fuel technology has been introduced, it has been met with a reactionary scepticism.

Jain cites the example of CNG, which underwent similar scepticism when it was launched. “When CNG was launched 15–20 years ago, there was a similar campaign against it. The campaign was that it would destroy the mileage of the vehicle and damage the engine; CNG would not be readily available,” Jain tells Fortune India.

Today, according to Jain, CNG has become a preferred choice for small cars. “Everyone wants CNG. For public transport, it was mandatory, but now people are opting for CNG willingly. These are the processes of conversion to any new fuel technology. There is always a lobby, or people are opposed to it,” he says.

To address the concerns people might have against ethanol-blended petrol, Jain said that the GEMA members anonymously interviewed people at petrol pumps. “We asked the members to anonymously ask whether ethanol-blended petrol is causing any problems in their vehicles. All those interviewed said that ethanol is fine. None of the interviewed people has said that my vehicle is deteriorating or that my engine is deteriorating,” he says.

According to Jain, the government’s ethanol-blending programme, apart from saving foreign exchange reserves, facilitates rural development and employment. “This year, we supplied ethanol worth ₹60,000 crore, out of which ₹40,000 crore has been doled out to farmers. The same amount of money was being spent on importing fuel,” Jain says.

For rural employment, Jain avers that every production unit in the ethanol industry is located in metropolitan cities such as Noida, Greater Noida, Delhi, or Mumbai, but rather in rural areas, 40-50 kilometres, and sometimes even 100 kilometres, away from cities. “It is providing both direct and indirect rural employment. Wherever a factory is set up, a dhaba-wallah sets up shop, followed by a tea-seller, someone who patches punctures—there is an entire market in the vicinity. This gives indirect self-employment to people,” he says.

When asked about the pace at which India’s ethanol-blending programme is progressing, he explains that it is the support of the government—in tandem with the investors in the country—that has made this programme a grand success.

“The major factor was the investment that came in, and the entrepreneurs who relied on the government. They relied on the government to take it to the level to the best of their capability, and the government is taking it. After May 2025, we will have a 20% blended rate, up from 14% as of May 2024. Today, the average is 19-plus. We cannot touch 20 because we don’t have the mandate to go beyond 20,” he says.

On the question of why ethanol-blended petrol is not cheaper, Jain says that the pricing of ethanol depends on the price of feedstock and the price at which the oil marketing companies acquire ethanol. “It is contingent on what is paid to the farmers. Do you want to enrich the farmers or impoverish them? The ethanol plants are efficient, leaving no scope for any additional cost-efficiency. The government decides on the price that is to be paid to the farmers, based on the MSP, and we do the procurement based on this.”

For the ethanol industry, according to Jain, the procurement price has remained fixed for the past three years and has not been revised. “We are expecting a tender for 2025-26 this week or next week, but we are not hopeful that the price will be revised. That is a problem if the price of ethanol is not revised.”

In 2023, the government addressed the concerns of over-reliance on rice—a water-intensive crop—being used to produce ethanol, and therefore, also adopted maize to be used instead. “Before it was used to produce ethanol, maize was used for consumption in the poultry and livestock industries as fodder. We have to promote maize as a source of ethanol,” he says.

(INR CR)

The government is promoting the use of ethanol, but it cannot be expected that 12 million tonnes out of the 38 million tonnes of maize produced in the country will be supplied to the green ethanol industry overnight. “It is currently a stopgap measure. We make do with whatever maize is available, whatever quantity of broken and damaged, overproduced rice from the farmers.”

Another issue, according to Jain, is that the farmers are unwilling to decrease rice production, which is why the industry is sourcing rice to produce ethanol. “Farmers get paid adequately for producing rice. The farmer is concerned with the returns they would get if they had, say, ten acres of land,” he explains. Farmers get good benefits from rice because the procurement price of rice is strong, making the farmer confident that their produce will be sold at MSP, something which is not happening for other crops.

Jain also says that using stubble for ethanol production is currently not viable. “The viability of producing ethanol from stubble is questionable because of its huge capex and opex costs. This is why stubble is not being promoted as a source for ethanol,” he says.

The capital and operating expenditures for producing ethanol from stubble are ten times more than those of grain, biomass-based ethanol (G1 ethanol), which is currently an industry standard. “So, who will buy this ethanol? It will take time for stubble to be used for producing ethanol. Currently, it’s just not viable,” he avers.