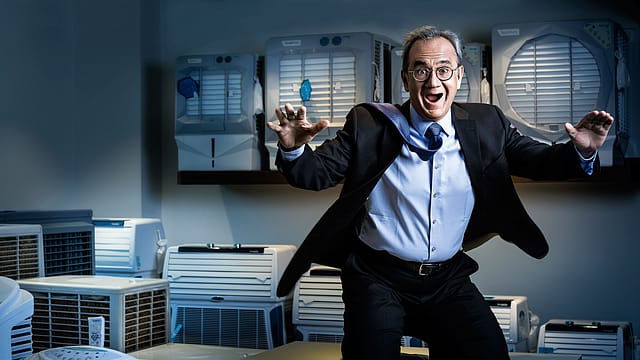

How Symphony got its rhythm back

ADVERTISEMENT

What’s common between a wealthy private-sector banker, a leading film actor, a Walmart store in the U.S., a Whirlpool factory in China, the holy shrine complex in Mecca, and several middle-class families in India? All of them use air coolers of one shape or another, made by Symphony, the world’s largest seller of air coolers.

A Mumbai-based banker enjoys some cool breeze, courtesy Symphony, when he sips his morning tea, sitting in the terrace garden of his luxurious apartment. A film actor, a leading man of many yesteryears’ blockbusters, has a Symphony air cooler installed in—believe it or not—his bathroom. The Walmart store, Whirlpool’s factory, and the shrine complex in Mecca use Symphony to cool their large premises, where installing air conditioners (ACs) just didn’t make sense. And middle-class families get some respite from the scorching Indian summer using Symphony’s air coolers, a much cheaper alternative to ACs

An impressive and diverse clientele, isn’t it? By assiduously focussing on innovating and selling one product, and one product alone, Symphony has become synonymous with air coolers in India and around the world, and built a profitable business in the process.

The Ahmedabad-based company ended fiscal year 2017-18 with a turnover of ₹854 crore—a six-year compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 19.27%; with a profit after tax of ₹193 crore— a six-year CAGR of 24.04%. Symphony’s market capitalisation is close to ₹8,900 crore and its stock price has tripled over the past five years. Based on its revenue, Symphony rose to number 325 on the 2019 Fortune India Next 500 list from 369 in the previous year’s list. But if one were to look at Symphony’s relative position among all listed companies in India vis-à-vis profitability and market value, Symphony ranks as a top 500 company on both parameters.

That’s quite an achievement for a single product company which its chairman and managing director Achal Bakeri, 59, started in the basement of an under-construction real estate project being developed by his family in Ahmedabad in 1988. It’s even more commendable when one considers that Symphony had a near-death experience in 2002 when a diversification strategy went awry. It became a sick company, with its net worth fully eroded, which was admitted under the purview of the erstwhile Board for Industrial and Financial Reconstruction (BIFR).

An architect by training who completed his MBA in real estate finance from the U.S., Bakeri returned to India in 1986 to join his family’s thriving real estate business. “When I joined the family business, it was already well established and I felt that as a newcomer, I would be just another cog in the wheel. I felt restless and wanted to do something on my own,” Bakeri says, sitting in his sprawling office on the top floor of Symphony’s aesthetically-designed headquarters in Ahmedabad’s Bodakdev area.

When the Bakeri family moved into its new home in the summer of 1987, it had its first brush with air coolers when it had to deploy some of them to cool areas of the house with high ceilings. Though effective, these coolers were ugly and noisy. “My father suggested one day: ‘Why don’t you make a better air cooler?’ Something clicked in my mind and I began working on the idea in earnest,” the Symphony founder recollects.

With little idea of how an air cooler works to begin with, Bakeri bought a few from the market and opened them up to understand the engineering. With the help of some technicians and engineering professors, Bakeri developed an air cooler that resembled an AC in its aesthetics, was compact in size, made of plastic, and thus lightweight and portable. The product was launched in 1988 in Ahmedabad, known for its dry and scorching summer heat, and met with instant success. “We were caught off-guard by the success and couldn’t keep up with demand,” Bakeri says. Priced at ₹4,300, Symphony’s first cooler cost a little more than 10% of what a 1.5 tonne AC cost in those days and operated at a fraction of the latter’s running costs.

Over the next few years, Symphony rapidly scaled up sales and distribution across India. It moved out of the basement in which it started operations and established a factory to manufacture air coolers. In 1994, Symphony had a successful initial public offering and was cruising along until investors and analysts called upon the company to leverage its brand and distribution to diversify into other household electrical appliances to counter the seasonal nature of the air cooler business, which booms during the summer months.

The company ended up getting into a wide variety of products such as water heaters, purifiers, washing machines, domestic flour mills, room heaters, and exhaust fans. Though Bakeri prides himself on the fact that Symphony was an innovator in many of these product categories and came out with designs that later influenced similar offerings from other brands, he admits that his company’s execution strategy to grow in these businesses was flawed. The shortcomings ranged from technical flaws in the product design of water heaters to uncompetitive pricing due to lack of scale in washing machines and the absence of a door-to-door sales strategy for water purifiers.

The net result was that Symphony found itself saddled with unserviceable debt; it had exhausted all its reserves and was referred to the BIFR. “We didn’t know if we would survive. But we were determined to do our best. Closing down the company and moving on to something else—leaving behind a trail of debt—would have been the easiest thing to do. But we didn’t want that,” Bakeri says. Between 2002 and 2004, Symphony exited all other categories except air coolers. The capital expenditure on these new initiatives had to be written off, but at least it saved on working capital. It resumed its focus on innovating in air coolers and came out with products priced between ₹5,000 and ₹20,000, boasting of features such as touch-based and motion-based control sensors, and mosquito repellent and air cleaning technologies. “We try and ensure that our rate of product innovation outpaces the rate at which our products are copied by others,” says Vijay Joshi, chief executive officer of Symphony’s India business.

Simultaneously, Symphony moved to an asset-light model under which it closed down its own factory and outsourced manufacturing to third parties while owning the design and intellectual property. The asset-light model has seen the return on capital employed (RoCE) from Symphony’s core business of air coolers improve manifold. Symphony’s consolidated core RoCE (excluding treasury income) stood at 90% in 2017-18. The company’s Ebitda (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation) margin also improved from 26.6% in FY12 to 32.1% in FY18.

Nrupesh Shah, executive director, corporate affairs, Symphony, says that wiser from its tryst with near-extinction, there are certain operational parameters that Symphony doesn’t compromise on, and which govern all its business decisions. “The aim is always to maximise RoCE from the core business and be in a situation where we enjoy at least 90% free cash flow from our profit after tax,” says Shah, who joined Symphony in 1993. “We have followed an asset-light, capital expenditure-light, and working capital-light business model, and focussed on innovation, new launches, and aftersales service. As a result, we have a 45% share of the organised market for air coolers by volume, 50% share by value, and 75% share of profits.”

Symphony’s other key business achievement has been its ability to sell its products in the trade channel against 100% advance payment, even during the non-summer months.

Bakeri says that his insistence on 100% upfront payment, even before Symphony became the brand it is at present, has some history to it. Apart from real estate, Bakeri’s family had some business interests in processed textiles. He observed that the real estate business didn’t face any challenges with respect to outstanding receivables since a buyer had to make the full payment before getting the keys to his house. On the other hand, the processed textile business would suffer from a cash flow mismatch as customers would pick up the product on credit and then renege on payment on flimsy grounds. And he wasn’t willing to take that chance with his venture.

“Dealers don’t mind paying for the coolers in advance, even during the off season, because they know that any prospective buyer looking for an air cooler is looking to buy a Symphony. And once he goes in asking for a Symphony, the dealer may cross-sell some other products to him,” says Bakeri. “Moreover, we incentivise the trade channel to buy from us during the non-summer months since we give them preferential rates that help their margins. Symphony means advance. No one questions that anymore.”

Also, from an earlier strategy of ‘one market, many products’, Symphony has since transitioned to a revamped strategy of ‘one product, many markets’. As a result, Symphony has tapped international markets with its residential and commercial air coolers—first via exports from India, and then through three acquisitions in countries as diverse as Mexico, China, and Australia—thereby increasing its size and scale. On the back of these initiatives, Symphony wiped out its losses and exited the BIFR in 2009.

While the period between 2002 and 2009 may have been painful for Symphony, it certainly learnt from its experience and used it to turn around the companies it acquired around the world.

In 2009, Symphony acquired IMPCO, the U.S.-based company that invented the air cooler in 1939, and manufactured the product from its facility in Mexico. Bakeri says his company acquired the business, which was bleeding at the time, for a song by paying the equivalent of ₹3.25 crore. In the decade since the acquisition, IMPCO has sold air coolers worth $100 million and yielded ₹100 crore in profits, Bakeri says. One of the ways in which Symphony managed to turn IMPCO around was by replicating its own asset-light model by hiving off its factory, which had become prime real estate, and outsourcing manufacturing IMPCO also played a strategic role in expanding Symphony’s horizons as it opened the company to the possibility of becoming a major branded player in the commercial and industrial cooling market. In 2011, Symphony started importing industrial and commercial air coolers from Mexico to India; and exporting residential air coolers from India to Mexico, thereby leveraging the synergies between the two markets.

Symphony followed this up with the acquisition of Keruilai, China’s first air cooler brand, in 2015. Again, Symphony bought the loss-making company for just ₹1.55 crore and helped it break even. Symphony expects Keruilai to be profitable from 2018-19 onwards. Guangdong Symphony Keruilai Air Coolers (as the company is now called), makes small as well as large air coolers and many of its products are now shipped to India and Mexico.

Then in 2018, Symphony acquired Climate Technologies, a profitable air cooler company based in Australia for around ₹200 crore. The company gave Symphony access to centralised air cooling solutions for residential purposes, as well as a larger footprint in the U.S. “Turning around Symphony after it was admitted under BIFR taught us lessons that we were able to utilise in China and Mexico,” says Bakeri. “We did simple things like reduce overheads and costs, become frugal with capital employed, and improved top line.”

Symphony’s products are available in 60 countries around the world, with 22% of its turnover coming from markets outside India. “It isn’t just the cost, but also the dry heat experienced by many regions around the world such as Arizona in the U.S. and the Middle East which make air coolers a preferred option over ACs,” says Falgun Shah, chief executive officer of Symphony’s international business.

But it isn’t as if Symphony is bereft of its share of challenges. Two erratic summers in 2017 and 2018 have led to a slowdown in the rate of sales growth. As a result, the company’s share price has seen a sharp decline of 33% over the past one year. “Two consecutive weak summers have made the Street believe that the air cooler category is not here to stay for long (we think otherwise). Symphony’s business model of channel-filling during off-season quarters has made its performance look even more challenging vs. air conditioner players (only optically),” says a research report dated December 27, 2018, by HDFC Securities. “We continue to remain bullish on the business and don’t perceive any change in competitive strength.”

To mitigate weak market conditions, Symphony is also looking to deepen its penetration in the trade channel in India. Rajesh Mishra, president of sales and marketing at Symphony, says that studies conducted by the company have shown that eight of 10 customers interested in buying an air cooler ask for a Symphony product; and five of them eventually end up buying one. The other three convert to other brands due to higher margins offered to the dealers by competitors. Mishra’s focus is now on ensuring that even the remaining three end up buying from Symphony by incentivising dealers through loyalty schemes as well as spending more on digital marketing.

Bakeri hopes that if India experiences a normal summer in 2019, Symphony can go back to recording its usual volume levels and top line growth. Meanwhile, the company is focussing more on international markets and industrial cooling to drive growth.

The company’s latest investor presentation for 2019 says that the market for centralised air conditioning in India is worth around ₹4,000 crore and the market for central air cooling could be potentially worth more than that. Industrial and commercial cooling products currently account for 8% of Symphony’s revenue and Bakeri feels this segment has the potential to account for as high as 25% of an expanded top line in the future. The rationale being that working conditions in Indian factories will gradually have to come on a par with international standards, and it is much cheaper to install and operate an air cooling system than a centralised AC unit in such large spaces.

Given some of the present challenges in the business, arising from its seasonal nature, does Bakeri feel the pressure to diversify again? “There is a lot of untapped potential in the air cooler market. We are conscious of not losing our focus again and taking our eye off the ball,” says Bakeri. He has realised that the answers to all his challenges have always been “blowing in the wind”.

This story was originally published in the March 15-June 14 special issue of the magazine.