Inside the mind of a chaebol

ADVERTISEMENT

IT'S A 90-MINUTE DRIVE from the South Korean capital of Seoul to the town of Namyang. Nobody seems to know where the place is; I ask a couple of passers-by on the Seoul streets how best to get there, and they pull out their smartphones and put the world’s most advanced mobile network to use. One gives up, saying there are too many similar-sounding names across the country; the other, after a painstaking search, finds it on the east coast, 40 kilometres away. What’s there to interest foreigners, the man asks, puzzled. Namyang is Hyundai Motor Company’s (HMC) secret weapon—the hi-tech research and development (R&D) unit designs and tests vehicles that are then made globally. The man knows HMC. Almost every vehicle on the road wears the distinctive H; others are by Kia, a HMC subsidiary.

More nifty work with the smartphone and my helpful guide tells me it’s better to take a bus or train to Namyang than hire a cab; the traffic is horrendous, and Korea’s luxury buses (made by HMC) are more comfortable than cars. However, being driven there in an Equus was as comfortable a ride as any I’ve had.

Getting past the forbidding walls of the Namyang facility is not easy; we are allowed in only because we’ve got permission from Hyundai-Kia towers in the Yangjae-dong area of Seoul, HMC’s global headquarters. The almost paranoid attention to security is understandable, with cut-throat competition in the industry. But in 1995, nobody took much notice of the R&D facility being created by the then vice chairman of Hyundai R&D, H.S. Lee. His orders came from the chairman and founder of the company, Chung Ju-yung. The brief: Convert the boggy land in Namyang into a world-class R&D centre. Today, it creates waves with its fluidic design, lithium-polymer batteries that are 40% smaller and 35% lighter than conventional metal hydride ones, exciting concept cars, and so on. The facility has allowed HMC to be entirely self-sufficient in the automotive technology and design. This also reflects the Korean culture of self-reliance.

January 2026

Netflix, which has been in India for a decade, has successfully struck a balance between high-class premium content and pricing that attracts a range of customers. Find out how the U.S. streaming giant evolved in India, plus an exclusive interview with CEO Ted Sarandos. Also read about the Best Investments for 2026, and how rising growth and easing inflation will come in handy for finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman as she prepares Budget 2026.

HMI’s latest small car, the Eon, was developed at Namyang. It has sold 8,000 units every month since its launch last year. Some 600 engineers worked on the Rs 900 crore project. The manpower and budgets are standard for almost any car with the Hyundai marque. Also standard and known only to insiders is that all specifications—from the kind of alloy used in wheels to the size of the door handles—are dictated from the 21st floor of its headquarters. Even today, Korea HQ decides the look and components of the cars made in the U.S., China, and India factories although they have smaller R&D units for localisation.

Namyang remains the group’s mother ship for R&D but in future the Hyundai Motor India Engineering (HMIE) in Hyderabad could become a major satellite serving the Indian market. Set up in 2009 as a software and engineering support centre, HMIE has been allowed to develop some components on its own for models that will be launched globally. It is working towards independent status, and chances are that it will be responsible for a car made entirely for India from scratch by 2016, without much interference from Namyang. “It is the baby of Namyang, built to cater to the tastes and needs of the Indian car user,” says K.O. Lee, the new managing director of HMIE. When the Eon was being designed, the Hyderabad engineers made several suggestions including a voice recognition software for navigation, and a bi-fuel engine. “The focus is now on future cars and acquiring capabilities from Namyang to build a new car for India,” says Lee.

An official of a Japanese auto company, who did not want to be identified, says an R&D unit outside the company’s main base reflects the company’s confidence in and the maturity of the market. India is key to the company’s strategy to become one of the top four carmakers globally, up from No. 8 in 2008. In a way, it’s trying to replicate Maruti Suzuki India’s (MSI) phenomenal success here. Like MSI, the success of Hyundai Motor India (HMI) has come from small cars, and both companies have created strong auto supplier ecosystems around their factories. The difference is that while MSI has cars at every price point including multiples per segment, HMI offers one or two cars in each customer segment.

Then there’s the focus on Indian R&D. MSI too is encouraging engineers from India to work at its research facilities in Hamamatsu, in Shizuoka, Japan, and has been putting together an R&D and road test lab at Rohtak, Haryana. In a conversation with Fortune India two years ago, Kohei Takahashi, auto analyst at J.P. Morgan, Japan, had said that Suzuki had to give greater importance and autonomy to MSI to remain No. 1 in the small-car segment globally. HMC seems to be doing that in India.

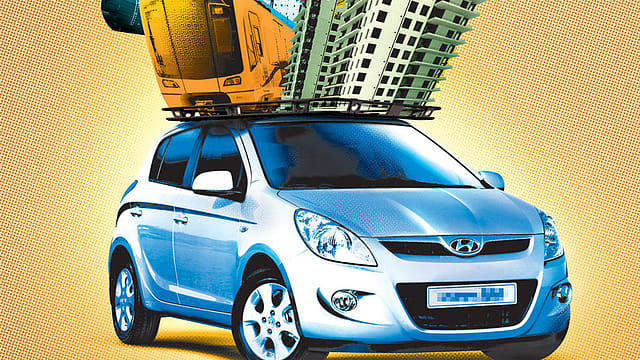

But there are departures from MSI’s approach. Between HMI and HMIE, the Hyundai chaebol (South Korea’s distinctive family-controlled business conglomerate) is throwing its considerable weight behind its India operations, flanking them with group companies that provide everything from logistics support to marketing and advertising services. Behind the scenes, there are as many as 63 group businesses collaborating to script the success of the automotive business. Analysts who track the company say HMC’s strategy is to use auto as the core and then build everything around it. It stands to reason: Though HMC makes a range of products from steel to locomotives, automobiles define the chaebol.

HMI gets logistics support from Hyundai Glovis, components assistance from Hyundai Mobis, steel from Hyundai Steel in Korea, and IT support from Hyundai AutoEver. Of HMI’s 119 component suppliers, 40% are joint ventures (JVs), such as Gyeongsan-based SL Corporation which has joined with Delhi firm Lumax to supply lamp, trim, and chassis parts. Then there’s Incheon-based Kyungshin Industrial Company which has a JV with Noida-based Motherson Sumi Systems to supply wiring harnesses. Such JVs ensure that HMC has full control over and uniform quality standards for every aspect of manufacturing and sales. By trying to replicate in India what it does in Korea, the chaebol is perhaps also looking to replicate HMC’s dominance of the roads.

“The model of doing everything in house, at least for components, was started by Henry Ford. It worked for him. How long it does for HMC remains to be seen, especially when they have businesses beyond components such as steel, logistics, and even advertising. The chaebol essentially controls everything from converting iron ore into steel to completed cars, while others focus on core competencies such as assembling the car and simultaneously managing component suppliers to ensure a steady flow of parts,” says Sanjeev Rana of Deutsche Securities in Seoul.

Another Seoul analyst says that HMC likes keeping everything in house as much as possible because it improves both quality and productivity. He points to HMI’s factory capacity utilisation of 109% in the first five months of 2012 and over 104% last year.

“Until China gets its third plant and hits 1 million units [in capacity], Chennai is the largest overseas operation,” says HMI’s managing director, Bo Shin Seo, who says he is proud of HMI’s capabilities. His appointment in March 2012 is seen as HMC’s effort to squeeze efficiency and improve the cost competitiveness of Indian models. Bo has had a thirty-year career with HMC and his previous assignment was handling production at the Hyundai factory in Alabama, in the U.S.

THEN CHUNG MONG-KOO took charge of the Hyundai Motor Group in 2001 as global chairman and CEO, his focus was to improve the quality and looks of HMC products; Toyota was the benchmark, and targets were based on the Japanese company’s sales figures and quality standards. Chung Mong-Koo wanted to prove that Korean cars could compete with the best in the world. His efforts seem to have borne fruit; in 2009, the Genesis was declared the North American Car of the Year, an award based on the recommendations of 50 auto journalists. This year too, an HMC car—the Elantra—has been declared North American Car of the Year. It is being launched in India on Aug. 13.

Globally, HMC banks on its premium models such as the Equus, Genesis, new Sonata, Elantra, and Verna. In the U.S., HMC has a 5% share of the market, around 3% in Europe, and 6.1% in China. In Korea, of course, it’s the dominant player with a market share of close to 80% (this includes Kia).

The U.S. and Europe are prestigious markets, but HMC’s idea is to grow the Indian market, which today contributes 15% of the company’s global sales by volume. In value terms, India contributed 6.5% of total sales in 2011. “India is a focus market. Unlike Europe or the U.S., it demands value-for-money products that have a good resale value,” says Y.K. Koo, senior vice president, Asia-Pacific, Africa, and Middle East group, HMC.

HMI has a 20% share in India, second only to MSI which has 36%. Other than Tata Motors, which accounts for 12%, no other car manufacturer in India has managed to cross the double digit mark. GM, Ford, and Volkswagen are all below 4%; Toyota a little over 8%. Much of HMI’s market share comes from its small cars—the Santro, i10, and the Eon.

The Santro (Atos Prime globally) was the first car to roll out of the 535 acre Chennai factory in 1998. HMC favoured entering India with the Accent, a mid-size sedan, but the local team pressed for a small car to take on MSI and Daewoo Motors. While MSI has since phased out its popular 800 and Zen models and Daewoo has downed shutters, the Santro is going strong; some 5,000 are sold each month, despite HMI rolling out newer models in the segment.

The company is now trying to gain traction in the premium segment, and insiders believe it is succeeding. “The gap between HMC’s Equus, Genesis, and Elantra, and BMW or Audi models has narrowed. They have taken a conscious decision to keep premium prices and break the perception of being a cheap carmaker,” says a former HMI marketing executive. The Eon, he adds, has been priced above any other small car: Rs 3.8 lakh for the top model, compared with Rs 2.92 lakh for the top model MSI Alto. The word on the street is that HMI refused dealers’ requests to lower the price justifying it with the numerous features provided. One result of this strategy is that HMI may avoid Suzuki’s fate of a low average realisation per car because sales from India weigh down the realisations worldwide.

But not everything has worked for HMI. One challenge is making a dent in the SUV/MPV segment. Though the company displayed the eight-seat MPV HexaSpace at the Delhi Auto Expo 2012, it is nowhere near commercialising such a vehicle. It also does not have a compact SUV to match the Ford EcoSport, the Renault Duster, or the MSI Ertiga. “HMI has been asking for a small MPV for Asia; we are evaluating the demand,” says Y.K. Koo.

Analysts say this approach could hurt the company in India. There appears to be a lack of product and technology strategy for India. “Not just HMI, everyone has to respond to market demands really fast,” says Abdul Majeed, executive director, PricewaterhouseCoopers India. Arvind Saxena, director, marketing, HMI agrees. “We have to be more proactive.” (Saxena resigned in July 2012 and a former MSI official, Rakesh Srivastava, replaced him.)

The diesel engine strategy is one such victim. While MSI and Ford raced ahead with diesel variants of their small cars, HMI is still waiting for clarity on regulations, and imports diesel engines for its larger cars; no car smaller than the i20 has a diesel version. The company has only recently announced that it is setting up a diesel engine plant (100,000-engine capacity) near its existing Chennai factory with an investment of Rs 400 crore. It has already increased imports of these engines from Korea by 50% to 10,500 each month.

BO says the Chennai factory can produce luxury cars such as the Equus, but the market for these vehicles is too small now to justify tweaking the line. T. Sarangarajan, vice-president (production), HMI, explains that the Chennai factory’s production lines are among the most flexible in the industry; the same line rolls out i10s, i20s, Santros, and Eons, and can be tweaked for the Verna and Sonata as well as larger cars if needed. Some 1,600 variants pass through 185 robotic arms and manual interventions before they are parked for shipment at the factory stockyard. On any given day, at least 30,000 cars are ready for the domestic and export markets.

The containers used to transport these belong to HMC’s in-house logistics company, Glovis. The chaebol also uses Glovis to ensure that its factories across the world get finished steel from its steel plants—Hyundai Steel, Hyundai Hysco, and Hyundai BNGSTEEL—which meet 35% of HMC’s needs. “Having an in-house logistics company controls the cost structure. Toyota does not own such a company but has joint ventures with U.S.-based Trans-System Inc. They ensure the best way to deliver cars and manage the back end. Being a partner, Toyota has partial control over the operations,” says Shekar Viswanathan, deputy MD (commercial), Toyota India. Honda, meanwhile, has an in-house logistics company in Japan but not in India. But Honda refuses to talk about it.

One of the most visible of HMC’s group companies in India is ad agency Innocean Worldwide. “Owning an advertising company is important because you cannot have different messages for the same car in different markets. The agency grows with the client. The overall philosophy needs to be uniform globally and this is serviced well with an in-house agency,” says Viswanathan. Toyota does not have an in-house agency, but, like most Japanese companies, it uses Japanese agencies Hakuhodo (in India as Hakuhodo Percept), and Dentsu.

Vivek Srivastava, joint MD, Innocean Worldwide India, says his single large client is more than enough to have kept his 45-member team busy for the past six years. “From the outside, HMI is just one, but the nine models require separate servicing teams. Each behaves like an individual client and there is never a dull moment.”

Another group company, Mobis (earlier called Hyundai Precision) was already supplying assembled modules to the Chennai plant. It has now been given the task of reducing fake and garage sales of spares. Mobis coordinates with suppliers, negotiates prices, and feeds spares to the market. “We improve the availability of original spares through real time monitoring and planning of 70,000 parts at any given time,” says P.S. Bhumak, general manager, sales and marketing, Mobis India.

How some of these businesses came up offers a peek into how HMC thinks. For example, the company used outside ad agencies till 2005. But as its push into Europe and America intensified, it felt the products weren’t being correctly positioned. So, J. B. Park, who was heading BBDO in Korea, was hired to establish Innocean and within a year India and China offices became operational.

Then, when HMC realised that Korean steel giant Posco might squeeze supply as global demand and prices went up, the steel business was reinforced by acquiring Hanbo Steel in 2004. It is said that Chung Mong-Koo personally monitored the commissioning of two blast furnaces in 2010, totalling a 20-tonne capacity, and flew to the construction site every week to assess progress.

Cross holdings abound. Hyundai Steel is 21.3% owned by Kia Motors, while the chairman owns another 12.5%. Chung Eui Sun, vice chairman of HMC and the chairman’s son, owns 31.9% of Hyundai Glovis, Chung Mong-Koo owns another 11.5%, and HMC owns 4.9%.

Not everyone is enthusiastic about the benefits of HMC’s approach. An insider in the Indian auto component industry says the company implements the chaebol mindset in each market it enters and is horizontally more integrated than non-Korean companies. This means that Indian component R&D suffers;everything developed here needs Korean approval before they can be adopted.

Such criticism doesn’t affect the company. In the highly controlled Korean chaebols, it’s called “resource circulation business structure” where each company helps another. More important, this ensures the money remains within the family. Compare this with Tata Motors. Although the Tata Group has diverse interests in companies ranging from software to steel they are not necessarily the only option for Tata Motors; the company is free to choose its vendors depending on its needs, says a manager at Tata Motors on condition of anonymity.

Meanwhile, HMI is talking of HMC’s finance business, Hyundai Capital, entering the country once regulatory issues become clear. In FY11, Hyundai Capital was the second biggest contributor to the group’s revenue (9.5%) and profitability (15%) after the automotive business.

But what has most people in the industry talking is Kia Motors’ entry in India. Kia officials were unavailable for comment, but those in the know say that a move seems imminent, now that H.W. Park, Bo’s predecessor, has been recalled to Seoul as CFO of Kia Motors. “Park understands the India market and his presence would make it easy for the company to chalk out a strategy for this market,” says an HMI executive who has worked with Park.

Much of HMI’s hopes are riding on Chung Eui Sun, who was responsible for the strategy that ensured the successful launches of the three luxury models in the U.S. He is bringing in fresh blood and carrying out management changes to prepare the global company for the next phase of growth. Insiders say that when he visited India last month, he asked the local R&D team to prepare for a far greater role in future strategy and new products for the company. That’s something the market is also awaiting.