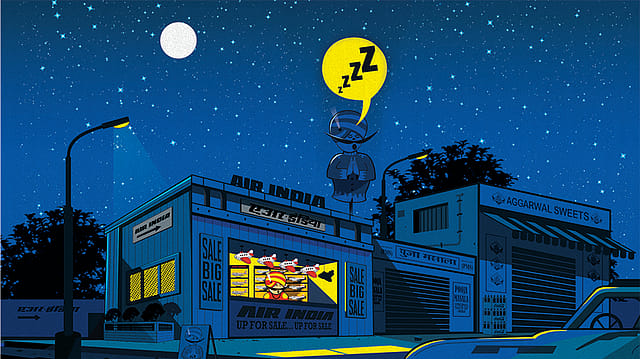

Air India: Stalled before take-off

ADVERTISEMENT

When Air India’s iconic maharaja abdicated his throne for a younger version in jeans and spiky hair in an effort to connect with the masses in 2015, many hoped the new mascot would mark a fresh beginning for the loss-making airline. For years, the national carrier had been a quintessential white elephant for the government with massive debt on its books and a reputation for being highly inefficient and bureaucratic. But just a cosmetic logo change wasn’t enough. Despite the government’s efforts to pump in millions to keep the flagship carrier solvent, Air India continued to make losses and it seemed like it was only a matter of time before it was finally put on the block.

So, when the government announced its decision last year to sell Air India and its subsidiaries, the industry wasn’t surprised. What was surprising was that despite Air India’s debt of Rs 51,000 crore, several airlines were keen to join the race for the state-run carrier. Budget carrier IndiGo was one of the earliest to express interest; others such as Jet Airways, Tata Sons, and a few global airlines followed suit.

Perhaps it was Air India’s storied history that attracted suitors. It began its journey as Tata Airlines in 1932 when legendary entrepreneur J.R.D. Tata flew its first single-engine de Havilland Puss Moth, carrying air mail from Karachi to Bombay’s Juhu aerodrome, and on to Madras (now Chennai). There was no turning back after that. After World War II, Tata Airlines became a public limited company in 1946 and was rebranded Air India. After Independence, the government acquired 49% of the airline in 1948. On June 8, 1948, Air India launched its first international flight when a Lockheed Constellation L-749A named Malabar Princess flew from Bombay (now Mumbai) to London. Eventually, India’s first international airline was nationalised in 1953 as part of post-Independence India’s tryst with socialism.

So far, so good. For years, it was a profitable airline, and in the 1960s and 1970s, it was synonymous with luxury and sophistication. In its heydey, it had a valuable art collection that included works by renowned artists such as M.F. Husain and Jatin Das. There’s a story that in 1967, it even commissioned Spanish artist Salvador Dali to create a limited edition ashtray for select passengers.

But the airline’s fortunes dived after it was merged with Indian Airlines in 2007. Its domestic market share shrank from nearly 20% in 2010 to 13.3% last December. Today, the beleaguered carrier is up for sale, and so far the government’s plans to privatise the airline seem to be grounded even before takeoff. Already, IndiGo and Jet Airways have opted out of the race largely because of the conditions of the sale in a key bid document called the preliminary information memorandum (PIM) unveiled in March. Speculation was also rife that Air India’s huge debt burden was the main reason behind their exit. Despite the troubles, interest in the national carrier hasn’t dimmed. Several leading players—including British Airways, Lufthansa, Etihad Airways, Singapore Airlines, and Malaysian Airlines—have shown interest in buying the airline, a senior Air India official told Fortune India on condition of anonymity. “We continue to expect significant investor interest as it will be a valuable asset for strategic and financial investors,” says Kapil Kaul, CEO of aviation consultancy firm Centre for Asia Pacific Aviation (CAPA), South Asia.

The government has a flight plan chalked out. In January, it divided Air India and its subsidiaries into four parts for sale as different entities. Air India, Air India Express Ltd (AIXL), and a joint venture with AI/Singapore Air Transport Services (AISATS) were clubbed together as one entity. On the other hand, Air India Engineering Services Limited (AIESL), Air India Air Transport Service Limited (AIATSL), and Alliance Air will be sold separately to get the best value. Two months after paving the way, the government came out with the PIM seeking to sell a 76% stake in Air India, 100% of AIXL, and a 50% stake in AISATS, the premier airport services company in India. The government has finalised May 14, 2018, as the last date for expression of interest (EoI). “The EoI is well structured and aligned to generate interest from investors. It attempts to balance the needs of stakeholders while moving the process forward,” says Kaul.

One of the biggest concerns potential bidders have is about possible government interference, given its 24% stake. Other likely sticking points that could force the government to tweak the process are the conditions that the winning bidder has to stay invested in the airline for at least three years and has to retain the Air India brand for a minimum number of years. The condition that bidders should have a net worth of Rs 5,000 crore and show profits in three of five preceding financial years could be another deterrent. Kaul says except IndiGo, other Indian carriers do not have the resources to bid for Air India. However, the profit requirement doesn’t apply to domestic carriers bidding as part of a consortium. “Opting out may be a compulsion, and not by choice. Some of them opting out does not necessarily dilute the value and prospects of this divestment,” he says.

The Air India official says the government was never too keen on Jet Airways. “Its financials have not been very strong, and if the company has deferred its employees’ salaries, it rings some serious alarm bells. Hence, we were not too keen on Jet Airways,” he says. But why did IndiGo walk out in April? “We would have liked them to be on board. They wanted the government to separate Air India’s international and domestic businesses, which was not possible. Such a request was never made by any other carrier,” he adds.

The reason for such a request was the watchdog Competition Commission of India (CCI). If IndiGo had acquired Air India, the collective domestic market share of the airline would have been over 50%, which would have led to problems with the regulator. “We do not believe that we have the capability to take on the task of acquiring and successfully turning around Air India’s entire airline operations,” IndiGo president Aditya Ghosh said in a statement.

But if IndiGo, Jet Airways, and SpiceJet are not in the race, who is likely to walk Air India down the aisle? At least four foreign players, including Singapore Airlines, have expressed interest in buying the troubled carrier. “Informal communications have been made to us by foreign carriers. They are in talks with Indian industrial houses to partner for the bids,” says the Air India official. On April 11, World Bank Group member International Finance Corporation ( ) said it was interested in underwriting the bid. A few other players—such as Air Arabia, Turkish ground handling firm Celebi, and Swiss Aviation—have also shown interest, but the government is not sure they will eventually bid.

But why would an ailing airline marred by losses and mounting debts generate so much interest? Quite simply, it is still attractive because of its massive fleet, lucrative domestic and international routes, hundreds of parking slots at major airports, including London’s Heathrow and New York’s JFK, and prime real estate in India and abroad. And its total assets are valued at a huge Rs 45,915 crore, which includes Air India and AIXL’s collective fleet of 138 aircraft. Another 16 are on order.

“The ability to get a large fleet at its disposal overnight can be an attractive proposition in an industry where wait times can run up to a decade,” says Abhijeet Biswas, co-founder and managing director of 7i Capital Advisors, a Mumbai-based investment firm.

To add to this , Air India caters to 42 international destinations and over 70 domestic locations. It also has intangible assets such as bilateral rights and a frequent flyer programme that make it more attractive. Air India has 2.5 million frequent flyers and earns about Rs 7,000 to Rs 8,000 on each member. It is also the only Indian airline that is a member of the global Star Alliance, which allows it to share routes with other airlines to more than 1,300 destinations. “Air India’s massive network is very attractive for us. We don’t have that kind of access to the Indian market and Air India gives us that opportunity,” David Lim, India general manager of Singapore Airlines, told Fortune India earlier.

Air India’s former executive director, Jitendra Bhargava, says the intangible assets are highly valuable. “Getting prime slots in major airports across the world is not just expensive but almost impossible,” he says. “If an airline buys Air India, it will be catapulted into the mega-league within no time because of the sheer size of its network. Otherwise, it may take a decade for most airlines to reach that spot.”

But Air India’s bloated workforce of 16,834 employees remains a concern. Of the 11,214 permanent employees, nearly 4,200 are expected to retire in the next five years. Although the government will take the entire salary dues of Rs 1,298 crore on itself, buyers could be deterred by the condition that in case of retrenchment, they will have to roll out a voluntary retirement scheme in line with government norms. Kaul believes no one will invest billions in Air India to face union disruptions without firm commitments from the government.

The other baggage is the liabilities the buyer will be saddled with. The PIM suggests the buyer will get Rs 33,392 crore of the total debt of Rs 51,000 crore, which largely ballooned after Air India and Indian Airlines were merged into Air India Limited. The Rs 33,392 crore debt includes current liabilities and aircraft finance lease. However, if we deduct the current liabilities of Rs 8,816 crore from the total debt, the remaining liability works out to Rs 24,576 crore, which includes aircraft finance lease of Rs 8,175.9 crore. “Brand Air India, the employee base, and a higher-than-expected debt continue to be major deterrents,” says Kaul. “Up-front clarity on these issues, especially labour, is critical to generate interest.”

But it isn’t all bad news. One analyst says if the airline can deal with the debt and achieve an over 80% Passenger Load Factor (PLF), profitability can increase by between Rs 2,000 crore and Rs 3,000 crore. Air India’s March PLF was 83.6%, while Jet Airways was at 90% and IndiGo at 89%.

The government is optimistic about the sale, which it hopes to wrap up by the end of this year. It doesn’t believe the new owners will have to worry about the debt because much of it will be absorbed by a special purpose vehicle (SPV) the government has set up. It plans to park all its non-core assets such as real estate and art collections in the company called Air India Asset Holding Limited. The government also hopes its 24% stake will allow it to get a share of any potential profits made by the new owner.

“A significant amount of the debt will be in an SPV, which the government is setting up to absorb the unsustainable debt. So if we have to pay down some of those debts, then it is good that some people unlock the value and the government can get some of that value to pay down the debt,” Jayant Sinha, Minister of State for Civil Aviation, told Fortune India in February.

But, at the end of the day, selling Air India will be a challenge. At least one previous privatisation attempt failed because of political opposition. And this time the airline’s unions have also taken to social media with a “Save Air India” campaign to protest against its sale. The question is: Will the government succeed in selling the debt-laden carrier? Or will it be forced to tweak the terms of one of its most high-profile reforms?.

(The article was originally published in the May 2018 issue of the magazine.)