Where have all the workers gone?

ADVERTISEMENT

LATE LAST YEAR, the Confederation of Indian Industry and the Gujarat government commissioned a survey of 15,000 companies in the state to identify the shortage of skilled workers. It found that these companies had around 90,000 vacancies for positions from shop-floor workers to senior managers. The state government, which wants to make Gujarat a manufacturing hub, held job fairs and filled 60,000 vacancies; there is still a 30% shortfall.

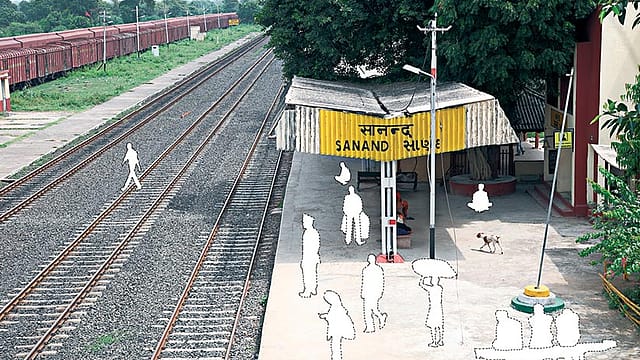

Automotive factories are the face of the government’s manufacturing hub plan. But to create the new Motown, the government as well as the companies have to close the skills gap. “While building your industry in Gujarat, build your workforce—that’s the government’s mantra,” says Dilip Chenoy, managing director of National Skill Development Corporation (NSDC) and former director general of the Society of Indian Automobile Manufacturers. Ever since Ratan Tata took the Nano project from Singur in West Bengal to Gujarat’s Sanand in late 2008, Tata Motors, Ford India, and Maruti Suzuki have committed to invest Rs 10,780 crore in the state. In support, an armada of auto parts manufacturers will follow. By the time the Ford India and Maruti Suzuki factories are ready in 2015, the state will have capacity to make 8.5 lakh vehicles, including the existing General Motors India (GM) plant at Halol, which can produce 1.1 lakh units.

The government has ensured power supply, access to 40 ports, better road infrastructure, and an efficient bureaucracy. “The only thing Gujarat’s auto industry is deficient in is skilled manpower,” says Vinnie Mehta, executive director, Automotive Component Manufacturers Association (ACMA). “The Gujarati gentry don’t believe in working for somebody else. They want to do something on their own.”

January 2026

Netflix, which has been in India for a decade, has successfully struck a balance between high-class premium content and pricing that attracts a range of customers. Find out how the U.S. streaming giant evolved in India, plus an exclusive interview with CEO Ted Sarandos. Also read about the Best Investments for 2026, and how rising growth and easing inflation will come in handy for finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman as she prepares Budget 2026.

Makrand Mehta, a former head of Gujarat University’s history department, states in his book Indian Merchants and Enterprises in Historical Perspective: “There is a broad consensus among historians that Gujarat evolved cultural elements that distinguished it from most other regions in the Indian subcontinent. These elements could be [identified as] business culture.” Devendra Amin, who hails from a Gujarati Patel family and has lived and worked in the state all his life, echoes Makrand Mehta. A 1981 product of the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, he worked for 26 years at Indian Petrochemicals Corporation before joining the Adani Group in 2007. “In Gujarat, the emphasis is on entrepreneurship,” he says. “That is the cultural mainstay.” Also, students choose to concentrate on commerce rather than technical education so that they are better equipped to handle their own businesses.

In such an environment, Gujarat has to develop a pool of skilled labour in the next three years if it wants to realise its auto manufacturing potential. “OEMs [original equipment manufacturers] in Gujarat will find it hard to get resources,” says Abdul Majeed, automotive leader at PricewaterhouseCoopers India. He is referring to mid-level engineers and skilled workers who work in departments such as paint shop, body assembly, and tool rooms. Automakers typically expect one-third to half of the labour to be sourced locally. But most prospects in Gujarat are semi-skilled or unskilled, and lack vocational education.

While deciding the manufacturing location, Majeed says, a company must ensure all resources are available; otherwise it may have to get labour from other states at a higher cost. Figures aren’t available, but estimates suggest that 60% of workers in Gujarat’s auto plants are migrants. Most are from Rajasthan, Jharkhand, and Maharashtra.

The skilled manpower target for 2017 at Gujarat’s auto hub is 54 lakh. But TeamLease Services, India’s largest staffing company, expects a shortfall of 10% by then. Manufacturing and operations account for 55% to 60% of an auto OEM’s manpower needs. The figure is higher—70% to 75%—for auto parts suppliers. Ford India plans to employ 5,000 in Sanand, which means it needs at least 2,750 people in manufacturing and operations. Maruti Suzuki and Tata Motors will need 1,500 each as they scale up.

The trend among the locals is to join the family business young, rather than spend time in classrooms. They’re not used to following a nine-to-five schedule, and with a school dropout rate of over 60%, literacy levels are low. “Even those who graduate, go into businesses,” says Neeti Sharma, vice president of TeamLease. This is in sharp contrast to the South Indian automotive belt of Chennai-Hosur-Bangalore, where locals prefer acquiring professional qualifications and being employed. Consequently, the south has seen the mushrooming of engineering colleges and private industrial training institutes (ITIs), which has created a vast pool of engineering and technical manpower. As the NSDC notes in a report published this year, South India accounts for about 44% of the employment in the auto and auto components industry. Tamil Nadu’s share is about 29%, while Karnataka’s is 11%.

In scouting for skilled workforce, Gujarat is pitted against the south belt and neighbour Maharashtra (the Mumbai-Pune-Nashik-Aurangabad belt). The auto clusters in both regions attract fresh graduates from states such as Uttar Pradesh, which has 1,109 ITIs. The North Indian state accounts for the bulk of migrant labour because of its low level of industrialisation.

“Whether the best technical talent from Chennai and the National Capital Region [Gurgaon and Manesar] will move to Gujarat depends on how the state government brands the auto hub,” says Aditya Narayan Mishra, who heads the staffing business for recruitment advisory Randstad India. He cites the example of Bangalore, which promoted itself as an IT city in the late ’90s to pull talent away from Hyderabad. It built an identity around infrastructure and kept the brand fresh with events such as BangaloreIT.biz, where technology vendors met prospective buyers.

Gujarat has begun building an identity as a manufacturing destination. “As much as the Nano was the proof of the pudding for Tata Motors, don’t forget Sanand gained acclaim as the project’s home,” says ACMA’s Mehta. “[Chief minister] Narendra Modi’s timing was crucial in creating Gujarat’s identity as an auto hub.” P. Balendran, vice president, corporate affairs, GM India, finds the government proactive and the state’s infrastructure robust. “In the 1990s, the commute from the Vadodara airport to our Halol plant took four hours. Today, it takes 35 minutes.” The next step for the government is to play up the story in colleges and training institutes.

The Directorate of Employment and Training in Gujarat has a team of 6,500 people that imparts training to 4.75 lakh students across ITIs, polytechnic institutes, and vocational training programmes. The government has developed a public-private partnership model. While it provides class infrastructure and facilities, the companies help upgrade technology and course materials.

GM India, for example, has introduced auto painting courses at the ITIs in Vadodara and Tarsali, and donated a Chevrolet Cruze to the Sardar Vallabhbhai National Institute of Technology in Surat so that the students can explore the technology. “Because of the private sector’s participation, the students are more job-ready,” says Sharma of TeamLease. “But the numbers are not high because there are only 406 ITIs in Gujarat.” To address this issue, the company plans to open a university each in Ahmedabad and Baroda in 2013, apart from 20 colleges in districts to impart vocational training to 60,000 people every year.

Companies are gearing up to deal with the manpower challenge. Ford India, whose Gujarat operations will begin in 2014, expects to have 3,000 employees by the end of 2013. In March, when it began constructing its Sanand factory, it recruited locals and trained them in construction and safety processes. “We have sought to create a mix in [recruiting] salaried employees,” says Kel Kearns, director for manufacturing at Ford India, who oversees the Sanand plant. “We are looking at local institutions, engineering colleges, and employment exchanges for salaried and hourly workers.”

For centuries, the entrepreneurial spirit has been Gujarat’s strength, so the auto industry is curious to see how its workforce develops against the grain. Few may remember today that Hindustan Motors, which manufactures the Ambassador, was set up at Port Okha in Gujarat before relocating to Uttarpara in West Bengal in 1948. More than six decades later, Gujarat’s Motown is taking shape. If only it could get enough people to get it moving.