Building a better fund

ADVERTISEMENT

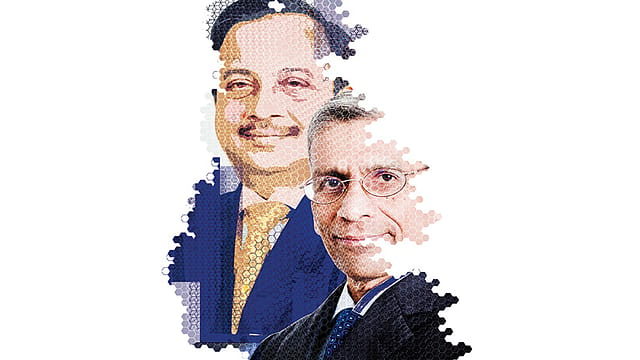

IT'S HARD TO IMAGINE Praveen P. Kadle or Yeshwant Moreshwar Deosthalee changing the face of financial services in the country. In an industry where success is defined by sharp suits and swanky offices, these two stand out for being so understated they’re almost invisible. They don’t flaunt their busy schedules, they keep their BlackBerry smartphones out of sight during meetings, and their offices are strictly utilitarian.

Kadle, 54, and Deosthalee, 65, are like the Clark Kents of the financial world; what you see is the studiously low profile, even as they take huge risks in a sector that already has a bad reputation. They both run non-banking financial companies (NBFCs): Kadle heads Tata Capital, while Deosthalee is at the helm of L&T Finance. Both were star chief financial officers of headliner manufacturing firms before moving to NBFCs: Kadle at the Rs 1.3 lakh crore Tata Motors, and Deosthalee at the Rs 53,883 crore engineering conglomerate L&T. Both groups have ambitions to set up financial supermarkets, and are serious about their NBFC businesses, which is why they have appointed their stars to head them.

Yes, there are others in the business, including biggies with serious muscle—Religare (set up by Malvinder Singh and Shivinder Singh with cash to burn following the sale of their drug firm Ranbaxy Laboratories), India Infoline, Indiabulls, and Motilal Oswal (all with big money backing them). But none of them has what Tata Capital and L&T Finance have: a solid background in manufacturing, years of working with dealers, and experience in building institutions.

There’s enough on the ground to show that this is working in the companies’ favour; between them, L&T Finance and Tata Capital account for 7% of the assets of all NBFCs in the country today. In a tough market for funds last year, Tata Capital raised $900 million (Rs 5,130.9 crore) in private equity capital. Last month, L&T Finance bought out U.S.-based Fidelity’s Indian mutual funds for Rs 500 crore. Earlier, it acquired a small mortgage firm to begin home financing. Says T.T. Srinivasaraghavan, managing director of Chennai-based NBFC Sundaram Finance: “They [Tata and L&T] are taking the conglomerate route to building their businesses as opposed to firms with a specialised focus.” Both the companies have loan books of over Rs 20,000 crore each, and are among the top 10 NBFCs in India.

THE NBFC SECTOR in India is generally seen as slightly shady. These companies are not banks; the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) doesn’t allow NBFCs to take deposits from people that can be encashed at will (they can only offer long-term fixed deposits).

The reason that NBFCs are seen as the finance industry’s black sheep is because, soon after liberalisation, they were allowed to take deposits from the public. Hundreds of NBFCs came up almost overnight, offering interest rates of 17% or 18% on deposits (regular banks offered 13% to 14%), and loans at 22% to 24%. Small companies found it easier to borrow from NBFCs, despite the higher cost of loans, because of their more relaxed norms than banks. In 1997, when the economy began losing steam, these companies were hit hard, and could not pay back the expensive NBFC loans. A string of defaults resulted in large NBFCs going out of business; listed companies such as Anagram Finance, Lloyds Finance, and Alpic Finance had to shut shop.

The RBI came down heavily on NBFCs, and the number of public deposit taking NBFCs (offering long-term fixed deposits) fell to 280 in 2009-10 from a high of 1,420 in 1997-98. The shakeout upset the Tata group as well. The precursor to Tata Capital was Tata Finance, and in 2003, its managing director Dilip Pendse was charged with misuse of funds and sent to jail. Pendse, who was considered a blue-eyed executive of chairman Ratan Tata, was in jail for 18 months before being granted bail.

The sector’s woes have not ended, though. It is mandatory for all banks to lend to the rural sector, which is classified as priority sector lending by the RBI. Till the regulations were changed in 2010, banks which did not have the capability to lend in rural areas, especially to buy tractors and commercial vehicles for rural transportation, employed local NBFCs to do the job.

But in 2010, the RBI came down heavily on this practice, and suddenly, a bunch of NBFCs were out of business. Then, some NBFCs offered loans to rural housewives against their gold jewellery; these companies took loans from banks to finance these loans. The RBI tightened the screws on the banks lending to these NBFCs to put an end to this practice. “Years of toiling to build an asset financing business vapourised as bank managers painted a single hue over all NBFCs and whittled down their lending,” says Srinivasaraghavan. He is also the ex-chairman of the Finance Industry Development Council (FIDC), a self-regulatory organisation for NBFCs which made several representations on their behalf.

IT IS AGAINST THIS BACKDROP that Kadle and Deosthalee are trying to set up their financial supermarkets. “We want to be able to give a customer everything he wants related to finance,” Deosthalee says. But can they pull it off?

Both are chartered accountants with great credentials and are well known in both corporate and financial worlds. When Kadle started at Tata Motors in 2001, the automobile giant was down on its luck. Poor sales due to the economic slowdown and defaulting dealers led to a Rs 500 crore loss, the biggest then in Indian corporate history. It was up to Kadle to pull the company out of the mess. He parcelled off the receivables and sold them to other finance firms. That gave him a deep understanding of how dealer channels and suppliers worked. He worked at paring costs in manufacturing and financing, and nursed the company back to profitability. He also devised the funding for Tata Motors’ first overseas acquisition of Daewoo’s commercial vehicle business in 2003 and later, stakes in Spanish and Brazilian firms. “Tata Motors gives you an end-to-end overview of all aspects of the business,” says Kadle.

Deosthalee, who was awarded the best CFO award by Asia Money, has spent over a decade at the helm of L&T, managing its finances and treasury. As L&T started executing projects in risky Africa, Deosthalee involved the company’s treasury in the process, from bidding to completion of projects. It did not oversee just forex risk but commodity price fluctuations too. During his time, L&T’s sales grew multifold as new models of infrastructure funding such as build-own-transfer and build-own-operate-transfer took shape. L&T Finance, the financing arm of the company, was set up in 1994 to help fund a few of its projects but some of its assets were transferred to L&T Holdings when the business was demerged in 2010. “The finance function in L&T was all about managing myriad business risks to maximise margins,” says Deosthalee.

BUT MANAGING AN NBFC is altogether another cup of tea. This month, the RBI is expected to act on the report and recommendations of a working group on the issues and concerns of NBFCs headed by RBI’s former deputy director Usha Thorat. The report has recommended that NBFCs should have more stringent capital adequacy norms as they increasingly borrow from banks for their activities. The working group fears that excesses by NBFCs, especially during hyper growth times, can harm the banking system. Already, banks have a big advantage over NBFCs as they have access to deposit funds such as savings and current accounts. The new regulation could increase the funding costs of NBFCs and further diminish their profitability. It puts the spotlight on how these two firms will execute their strategies.

Both Tata and L&T envisioned their NBFC strategy in 2006-07, when the economy and world markets were thriving. In the initial years, it appeared that their inherent understanding of the manufacturing business would open up more opportunities.

In reality, Kadle had initially planned a 50% retail play in building his loan portfolio. That has since been revised to 30% after banks also reported a scale back on retail assets. Kadle then used his understanding of the Tata Motors ecosystem, involving suppliers and dealers, to build his business. Tata Capital built a Rs 15,000 crore book, lending to corporates, many of them suppliers to Tata Motors. Then, it lent to several smaller NBFCs which had good relationships with clients in local areas. Even though margins were squeezed a bit, Kadle trusted agents in far-flung areas as he had worked with the distributors of Tata Motors. “It is an opportunistic strategy and not a deliberate one,” says a Tata Capital executive.

L&T Finance has a fairly large proportion of lending to infrastructure firms, a legacy that came to the business after it was hived off from L&T. The group continues to have its own financing division to fund projects, and L&T Finance has been looking at other clients too to build its books. N. Shivaraman, chief financial officer of L&T Finance, says, “We can easily take larger bets than a lot of others in the space as we understand this business thoroughly.” Deosthalee says there are only a few specialised firms such as Infrastructure Development Finance Company in this space and L&T Finance can build its skills here.

Ravi Bubna, president and co-head (credit and fixed income) of financial services firm Edelweiss Capital, tries to explain the quick ramp-up of the two firms in corporate lending. He says lending to businesses after a stint in manufacturing alters the perception of risk. In his early days, when Bubna moved from a manufacturing firm to join Birla Global, the Aditya Birla Group’s finance firm, he made his first loan of Rs 20 crore to a manufacturing firm. His move raised eyebrows as the firm was not used to lending that kind of money to new clients. Later, Bubna increased the loan to Rs 80 crore. By then, the matter had reached the board and a detailed discussion was held to evaluate the risk. “A person from a finance background will always try to curtail exposure, but someone who understands a business will see it as an opportunity,” says Bubna.

THOUGH THE TWO FIRMS have some of the biggest loans to corporates among private NBFCs, how far can corporate lending go? Banks compete in the same space and have the advantage of cheaper funds. The largest companies bank only with the top few banks. That would mean that NBFCs, which are lower in the pecking order, will have to be content with assets that are not of the best quality. Deosthalee disagrees. He says lenders who understand the risks of businesses will always be able to lend better to them. He points outs that GE Capital, one of the largest NBFCs in the world with a loan book of $120 billion, lent to specialised businesses such as airlines and infrastructure. It understood the risks of these businesses as it manufactured aircraft engines and huge power and infrastructure equipment. For FY11, its parent GE had an order backlog of $200 billion in infrastructure projects, its highest ever, signifying the lending opportunities for GE Caps.

Much of Kadle’s corporate loan book is still limited to the auto sector as he and a few executives who came from Tata Motors understand that industry best. Kadle says the knowledge of the Tata Group, which has 20 companies operating in broad areas from salt to software, will eventually help in expanding the scope of Tata Capital’s business. With an opportunity to deliver quick and visible results in Tata Capital’s PE funds, more executives with domain experience from across the group’s businesses are expected to work, at some time in their careers, in the finance arm.

Kadle’s team is already warming up with some easy pickings. In their Mumbai offices, executives are more than willing to sell you home loans. The more the down payment, the faster the loan process. If you have taken a bank loan before and have a good payment track record, the chances are the rates of interest will be better than banks. In fact, the home loan book of over Rs 5,000 crore is easily the biggest among Tata Capital’s portfolio of loans. “We have just begun,” says Kadle.

Though he is not paying top dollar, Kadle has a formidable team in investment banking, institutional broking, and mergers and acquisitions. His logic is that fee-based businesses are based on relationships and it will take a while before they can cut big-ticket deals. Tata Capital’s only acquisition so far is a forex firm to tie in with its travel and branded credit card business. Kadle has kept his sights low by focussing on medium-sized deals and taking his business to tier II and tier III cities, where the Tata brand gives them easy access to customers.

Deosthalee, with his deal to buy Fidelity’s mutual funds, showed a little more aggression. He says scale is a necessity in the asset management business, as evidenced by the continued growth of large firms such as ICICI Bank and HDFC Ltd. Fidelity’s equity schemes will add to L&T Finance’s existing portfolio. “We don’t look at anything as a new area of business. We made the Fidelity buy after building our capabilities just like we did in several businesses in L&T,” says Deosthalee.

BOTH CAPITAL AND L&T FINANCE are likely to apply for banking licences when the RBI allows them. Deosthalee earlier said it would be a natural progression for L&T Finance, though Kadle did not want to talk of banking. A CEO of a private bank, who did not want to be named, says, “Both Tata Capital and L&T Finance are nearing a book size of Rs 25,000 crore. It becomes imperative to have access to cheaper funds like a bank. Sooner or later they will have to make the crucial banking decision.”

NBFCs, unlike banks, currently don’t have to adhere to capital adequacy margins and set up branches. According to the RBI, the assets of all NBFCs (including the ones that don’t take public deposits such as Tata Capital and L&T Finance) have increased to Rs 6.6 lakh crore in 2009-10 from Rs 2.9 lakh crore in 2005-06 (CAGR of 23%). In the previous five-year period, the CAGR was 30.3%.

Groups such as the Tatas are eyeing the value they can create with surplus capital. For example, in 2005, Shriram Transport Finance, which lends to buyers of pre-owned trucks, had an asset size of Rs 5,000 crore and a market capitalisation of Rs 500 crore. In seven years, the value of its shares has shot up to Rs 36,000 crore. “Sectors such as retail lending will see high growth rates as per capita income rises,” says V. Vaidyanathan, vice chairman and managing director of Future Capital. Srinivasaraghavan adds that infrastructure is an assured story for the next 10 years.

Deosthalee says that 60% of Indians are still unbanked. Recently, ratings agency Crisil started vetting small and medium enterprises, opening up an opportunity to lend to over 200,000 such firms. With a mix of lending to projects that banks consider risky and keeping operational costs under control, NBFCs have shown 20% return on equity; as much as large banks. “There is a huge opportunity and if we do a good job, we can be better than banks,” says Deosthalee. Keki Mistry, director at India’s biggest non-banking mortgage firm, HDFC, adds: “As NBFCs lend to the same clients as banks, the distinction between the two will go away, at least from the regulatory point of view.” Once Tata Capital and L&T Finance turn into banks, business for them will be more glamorous.