Why repo rate remained unchanged in Apr review?

ADVERTISEMENT

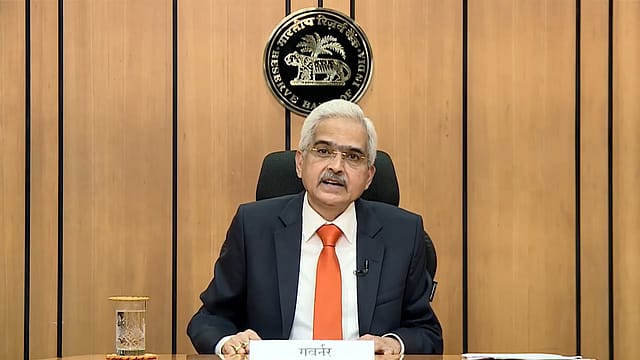

Why did the RBI's monetary policy committee (MPC) keep the policy interest rate (repo) unchanged at 6.5% in the April round of bimonthly monetary policy review will remain a mystery. Officially, Shaktikanta Das, RBI Governor and MPC member, offered two reasons. One, expectation of moderation in inflation in FY24, from 5.3% (February 2023) to 5.2% (April 2023) – even though the RBI’s estimations often go wrong. For example, the January and February 2023 inflation was 6.5% and 6.4%, respectively, far higher than 5.8-5.9% for the fourth quarter of FY23 it estimated. For FY23, up to February 2023, inflation is already 6.75%, which is more than its estimation of 6.5%.

Two, Das also reasoned that it is a mere "pause" for the MPC to "assess" the progress of monetary actions taken so far, which are "still working through the system." He assured that the MPC wouldn’t “hesitate” to raise the rate if and when required. At the same time, Das also announced "withdrawal of accommodation" to ensure that inflation progressively aligns with the target, while supporting growth – pointing to the possibility of hike in future.

The unchanged repo rate is not only against the expectation of outside economists who felt a hike by 25 basis points was in order but also for several other reasons listed below to indicate that the fight against inflation would continue for some more time.

MPC’s contra-intuitive move

There are at least six reasons why the repo rate should have gone up, rather than remained unchanged.

January 2026

Netflix, which has been in India for a decade, has successfully struck a balance between high-class premium content and pricing that attracts a range of customers. Find out how the U.S. streaming giant evolved in India, plus an exclusive interview with CEO Ted Sarandos. Also read about the Best Investments for 2026, and how rising growth and easing inflation will come in handy for finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman as she prepares Budget 2026.

Three of these are provided in the statements of the Governor and the MPC on April 6:

· Inflation is estimated at 6.5% in FY23, which would moderate to 5.2% in FY24 – both are higher than the legal mandate of keeping it at 4% (with 2% deviation on either side as lower and tolerance limits). This indicates a higher repo may be desired to achieve the 4% target.

· Growth estimate for FY24 goes up from 6.4% to 6.5% – reflecting no adverse impact of high repo rate on growth prospects for FY24.

· Dramatic rise in credit growth to non-food from 8.7% in FY22 (average of 6.8% during FY20-FY22) to 15.4% in FY23 – reflecting no adverse impact of high repo rate.

In its March 2023 bulletin, the RBI had given another reason.

· Not only inflation remains high, "core inflation" – consumer inflation excluding food and fuel – "continues to defy the distinct softening of input costs." The RBI didn’t probe or explain why this anomaly.

But sitting in the faraway New York University, Viral Acharya, former RBI Deputy Governor who is back to teaching, noticed the anomaly and explains it in his recent paper "India at 75: Replete with Contradictions, Brimming with Opportunities, Saddled with Challenges" (at BPEA Conference on March 30-31, 2023). He writes, "the persistence" rise of core inflation is may be "due to greater pricing power in increasingly concentrated industrial organisation structures." In contrast to the rest of the world, core inflation is rising in India "more in goods where its industrial sectors are increasingly concentrated," than in services, though early signs point to "pricing power rising" in the services sector too.

He, in fact, blames the Big 5 – Reliance, Tata, Birla, Adani, Bharti groups – for driving inflation through price rise unconnected to input costs because of (i) their monopoly in markets and (ii) their protection by "sky-high tariffs" – import barriers – India has imposed to protect domestic companies from foreign competition. The Big 5 dominate “manufacturing of metals, manufacturing of coke and refined petroleum products, retail trade, and telecommunications.” In the US and Europe, this phenomenon is called "sellers’ inflation" – an inflation caused by companies rising price to make more profit – and is increasingly a concern for the central banks.

The fifth and sixth reasons are:

· Brent price is on the rise – up from $77.6 per barrel on March 31, 2023 to $85 on April 10.

· Brent price is likely to go even higher as Saudi Arabia and other OPEC+ oil producers announced last Sunday to further cut oil output. They had already cut production as the crude prices fell from a peak of $120 to $72.

The RBI’s MPC must have been aware of these facts while announcing to hold the repo rate.

Afterall, the sole mandate of the MPC is to keep the inflation at 4% – with 2% leeway/latitude on either side. In case it fails to bring it down to below 6% – the upper tolerance level – for three consecutive quarters, it is officially considered as a “failure” of MPC and it is required to explain this to the government in writing – giving (I) "reasons for failure" (ii) "remedial actions" and (iii) "estimate of the time-period within which the inflation target shall be achieved."

This is meant to fix MPC's accountability.

But that seems far from the reality because it has failed twice since it came into being in 2016 but nobody outside the government knows why.

Is it MPC fixing repo rate?

When it failed for the first time in 2020 – three consecutive quarters between January and September 2020 inflation was 6.7% – it was the government which allowed the MPC to escape accountability by waiving off the need to send a report to it. Thus, the government helped the MPC to avoid its own mandate of keeping inflation below 6%.

It is happening now also.

In the first three quarters of FY23, the inflation is at 6.8% – it is already 6.5% and 6.4% in the two months of fourth quarter. This time, the RBI did send a report to the government in December 2022 but its content was not made public either by the government or by the RBI – both refused. The RBI’s stand is contrary to what it had said while the MPC and the rules governing it were being finalised in 2016-2017.

This raises questions about the MPC’s autonomy.

It is widely known that the government pressurised the RBI for years to lower interest rates. The spar between the RBI and the government often hit the headlines when Raghuram Rajan and Urjit Patel were RBI Governors.

Both Rajan and Patel resisted the pressures and didn't cut the policy interest rate as sharply as the government wanted. For this, a senior central government official had even accused Rajan of working for "the white man" in "developed countries" and sought a probe against him. After an initial compliance, even Patel refused to play ball. It was only after Shaktikanta Das took over in December 2018 that the repo rate began to fall, notwithstanding high inflation.

The repo rate fell from 6.5% in August 2018 to 4% in May 2020 – a very inappropriate time as the inflation averaged 6.7% for the previous two quarters. The rate remained unchanged until April 2022, despite rising domestic inflation (6.3% during January-April 2022), the Russia-Ukraine war causing supply disruptions and commodity price rise and the US and Europe were witnessing rising inflation and rising interest rates. The reverse repo (interest that banks get by parking their money in the RBI’s reverse repo account) was also lowered to 3.35% to flood the market with money – which eventually led to "liquidity trap" for nearly two years between April 2020 and October 2021 as banks were either unwilling to lend or high NPAs made them extra cautious. The reverse repo remains stuck at 3.35% even now (it was 6.25% when Das took charge).

It is no secret that after Das took over, the MPC kept the repo rate low during 2020-2022 to (i) keep the government’s interest outgo low since nearly 94% of the borrowing was from internal sources and (ii) also to allow the government to borrow more at low interest even while declaring that India was credit surplus and twice warning in 2021 that continuation of low interest regime and liquidity infusion posed “macro-financial risks” to the economy.

When it was raised to 4.4% in May 2022, this was an "off-cycle" action (the MPC didn’t raise it in April 2022) and the MPC was already "behind the curve" – which many had already said as the domestic and international developments (rising domestic inflation, the war broke out in February 2022, the US and Europe had already started raising bank interest rates due to high inflation). It is likely that this delayed response to inflation was also to help the government in debt management, rather than to tame inflation.

Will RBI and govt come clean?

Is the falling "behind the curve" happening again? We may get the answer to this in the next few weeks.

All six MPC members "unanimously voted" to keep the repo unchanged and hence, may not reveal their views on the six factors listed earlier – when the MPC minutes are made public.

The MPC’s move was all the more surprising since the US Fed and the European central banks had raised interest rates by 25-50 basis points just days earlier and after the two bank runs. The immediate cause of collapse of the US-based Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) is attributed to its failure to negotiate the rising interest rates (since March 2022) after a very long period of near-zero interest money and liquidity infusion – which impacted the UK too as the SVB’s UK unit had to be rescued.

A quote attributed to the late US investment banker JP Morgan says, "A man always has two reasons for doing anything: a good reason and the real reason."

By arguing that the repo rate was kept unchanged due to expectation of moderation in inflation (for which no evidence exist as the war continues, interest rates are rising in the US and Europe, crude price is going up and production of crude is being cut further etc.) and to "assess" the progress of monetary policy actions already taken, the RBI Governor may have given a "good" reason (though questionable) but is that the "real" reason?