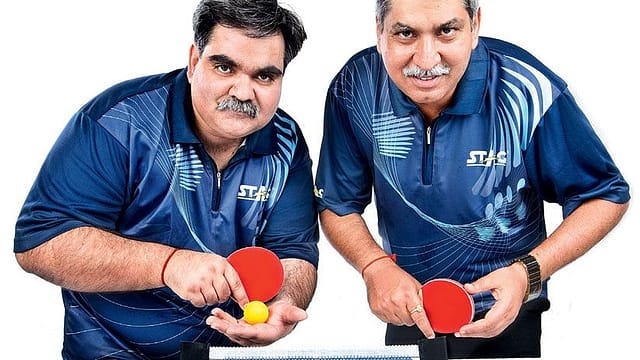

Brothers ping pong

ADVERTISEMENT

THE CONTRAST BETWEEN THE Kohli brothers, Rakesh and Vivek, of Stag International, is much like the difference between ping pong and table tennis (TT). Though the same sport, the references are U.S. specific: Table tennis is played at competitive tournaments, while ping pong is played as a hobby or recreation.

As chairman of one of the leading TT competition board manufacturers in the world, Rakesh Kohli, the elder, is every bit the sharp businessman and manager. In a full-sleeved formal shirt, the 53-year-old crunches numbers and describes the global markets for TT and other sports equipment manufacturing, charting Stag’s history, while driving his Audi Q5.

Ten years younger, vice chairman Vivek Kohli arrives in his Maruti Grand Vitara wearing a casual collared T-shirt. The former TT India No. 1 talks with a child-like love of the game, and advises clients on improving their technique (he taught us how to counter ‘chop’ shots). But he is most interested in technical improvements, such as cricket balls made with polyurethane instead of leather. If successful, the lighter ball will not only save hundreds of cows from being slaughtered, but change the way the game is played.

January 2026

Netflix, which has been in India for a decade, has successfully struck a balance between high-class premium content and pricing that attracts a range of customers. Find out how the U.S. streaming giant evolved in India, plus an exclusive interview with CEO Ted Sarandos. Also read about the Best Investments for 2026, and how rising growth and easing inflation will come in handy for finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman as she prepares Budget 2026.

The brothers’ combination of serious business and sheer passion has established Stag International as one of the most reputed Indian sports brands globally in TT, a game with the second-largest number of federation affiliations worldwide, after volleyball. As the biggest domestic producer, Stag is already the No. 1 table tennis brand in India; it is also the country’s second-largest sports equipment manufacturer and exporter, after Inca Hammocks. The company is also one of the five premium partners of the International Table Tennis Federation (ITTF).

Stag started out as International Sports in Sialkot, Pakistan. The company was set up in 1922 by Lala Arjan Das Kohli, Rakesh and Vivek’s grandfather, to manufacture guts for badminton racquets, football bladders, and footballs. After Partition, Kohli moved to Meerut, where he set up his first Indian sports equipment factory in 1950. Growth was slow initially. “In 1975, when the factory produced the first TT table for me, I knew things would change,” says Rakesh.

As the company gained momentum, the Kohlis decided to give it a new identity, and chose the name ‘Stag’ as a reminder of the speed associated with the animal. That was in 1981. “In 1983, the Table Tennis Federation of India (TTFI) provided us certificates approving our tables for use at the national championships,” says Rakesh. “They distributed them to various state associations; orders started pouring in and production rose.” Within two months Stag had orders for 100 tables, a big break for a company producing less than 10 tables a month.

Another break came at the 1991 World Championships in Japan. Vivek, as the company representative at the tournament, volunteered to send 10 free tables to one of the participants, Uganda, as part of the ITTF’s development programme. “Our revenues may be just Rs 45 crore, but we are a small company with a big heart,” says Vivek. The Ugandan national federation then paid Stag for 40 more tables and the global business took off. “Today, we have bulk orders from Fiji and Venezuela. Stag is hugely popular in lesser-known TT playing countries,” says Vivek. “We have consciously established our presence there. Bigger nations notice the quality of our products when they visit for tournaments.”

In 1993, the brothers found a way to make space in a market dominated by European and Chinese players. Stag’s TT tables were more expensive than those in the global market. “Our net set pricing and quality were unbeatable. We were priced at $2 (Rs 89.58) against the global cost of $5 a set, so we bundled equipment [tables with net sets],” says Rakesh. The higher priced tables were offset by the lower-priced accessories, earning sizeable profits.

“Our focus is to try to ensure good value for money: the best but not necessarily the cheapest product, unlike the Chinese,” says Rakesh.

Today, 45% of Stag’s revenue comes from TT equipment. With exports currently to 152 countries and a projected jump in turnover to Rs 550 crore by 2016, possibilities include increasing rubber products and the blades of TT bats, and diversification.

The Kohli brothers want to make Stag the global No. 1 TT brand. However, the company’s production (35,000 tables a year) is minuscule compared with global production at around 6 million tables a year. Most of the international TT market is shared between China’s Shanghai Double Happiness (DHS) and Double Fish, Germany’s Joola and the U.S.’s Escalate. Also, while Stag International’s 1000DX and Americas tables are approved by the ITTF, DHS and Joola have four and 10 approved playing surfaces respectively.

The greater market share that Joola or DHS enjoy could be because of their huge domestic hobby sport markets, which require different and cheaper equipment than competition tables. China’s 75 million players account for 85% of the global TT equipment market; Germany’s 300,000 TT clubs are the other major consumers. Offers such as $99 for a TT table at Christmas drive sales in the western market but are missing in India, where cricket rules.

“The direct competition between DHS and Stag is not fierce now, because each brand has unique competitive advantages and regional influence in their local markets,” says Terry Guan, marketing manager, DHS. Stag’s problem is that it is not alone in the Indian market: Joola and DHS have both entered and are fighting for their share of the country’s TT equipment market.

Rajesh Kharabanda, joint managing director, Freewill Sports, the sole licensee of Joola in India, and operator of the Nivia brand of sports goods, says Stags efforts to retain its top spot in the domestic market are commendable. However, he points out a problem with Stag’s Indian roots: “The perception of quality is a thin line globally when it comes to competition TT tables, and depends on technical aspects such as the correct bounce of the ball or the uniformity of the top-end surface right.” With the maximum number of tables being produced in China and exported mostly to Europe, Kharabanda says expert opinions on quality development and next-level innovative technology are often passed back to China.

The Kohlis, meanwhile, are banking on innovations such as attaching wheels for greater board mobility, or door-to-door transportation. Rakesh says that Stag’s biggest advantage is the brothers’ expertise in the game. “Since we were both players, we understand the product much better than our competitors.” Six out of the nine Kohli family members have played TT at the professional level.

Five-time Swedish world champion Peter Karlsson, and Kamlesh Mehta, a recipient of the Arjuna Award and Indian national coach and selector, are Stag’s brand ambassadors. They also help improve the quality of Stag products and open up new business avenues. For example, Karlsson was instrumental in opening the doors to Japan’s best rubber manufacturers. This was a coup, since good quality rubber improves the quality of bats and increases sales of standalone rubber sets (to replace worn-out paddle surfaces) internationally.

Domestically, as part of the ITTF’s development programme, Stag organises TT camps and provides free equipment. Orders follow once players and officials have used the equipment.

The brothers say that equipment development initiatives will continue, but the emphasis will be on higher business generation and diversifying into apparel and fitness equipment over the next five years. These are expected to contribute almost 60% of revenue by 2016.

Rakesh’s daughter-in-law, designer Vinita Nagpal Kohli, is creating the apparel line. “If we get even 2% of the kitting of Germany’s TT clubs, the business will be huge,” says Rakesh. His son, Pranav Kohli, who heads the fitness equipment business, plans to get Indian distribution rights for 50 international sports brands. He already has the Tunturi, Victor, and Milon brands, and plans to open retail stores in Bangalore and Delhi, with a total of 22 stores to open by the end of the year.

So, what are the rules of the game for Indian enterprises aspiring to make a mark on the world stage? Rakesh says that quick response to queries, regular correspondence, spot-on delivery timings, and commitment, are key factors while serving a global clientele. “More important than pricing, or the volume of business, it’s the quality of service that really counts,” he says.

His brother agrees. “Even in TT, it’s the service that counts. It’s the only shot over which you have full control,” explains Vivek. Be it pointers on business or the game, these guys make a potent doubles team.