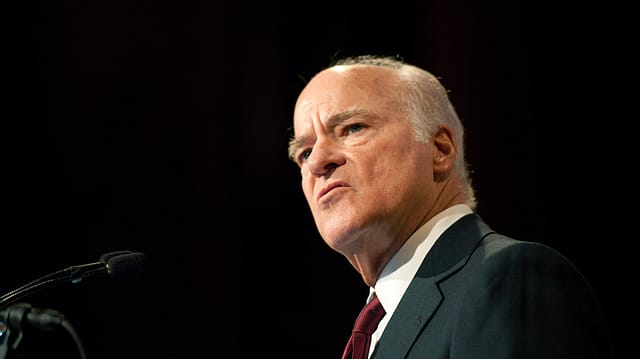

KKR’s Henry Kravis says ‘bad banks’ must to tackle NPLs

ADVERTISEMENT

Henry R. Kravis, co-chairman and co-CEO of private equity giant Kohlberg Kravis Roberts (KKR), feels it is time the Indian government and financial system pushed ahead the concept of ‘bad banks’—banks where bad loans would be housed—to tackle the serious problem of mounting non-performing loans (NPLs) in the banking sector.

A very good asset quality test was needed to understand the extent of the NPL problem, and the ‘bad bank’ would then take on the problem loans. This, he said, would free up the banks to raise fresh capital and get back to lending and funding the needs of the corporate sector.

Speaking to select journalists during a visit to India, Kravis, who, together with his first cousin George Roberts, co-founded the firm in 1976 to create what is today a financial giant with $195 billion in assets under management, said NPLs in Indian banks were a serious problem and the government needed to “take the tough medicine” and move to a “good bank-bad bank” scenario.

January 2026

Netflix, which has been in India for a decade, has successfully struck a balance between high-class premium content and pricing that attracts a range of customers. Find out how the U.S. streaming giant evolved in India, plus an exclusive interview with CEO Ted Sarandos. Also read about the Best Investments for 2026, and how rising growth and easing inflation will come in handy for finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman as she prepares Budget 2026.

“India’s got areas that need improvement. You have no capital market here. You have a stock market of sorts, but you have no bond market. If you don’t have a long-term bond market, you’re limiting growth because you’re putting all the onus back on the banks to be the providers of capital,” Kravis explained. “And when the banks run out of capital or when they say we’ve got to stop right now because we’ve got all these NPLs and we’re not sure what the RBI wants, you’re going to strangle mid-sized companies.”

“If you have NPLs in banks you can pretend everything’s fine, but that’s a mistake. Take the tough medicine and go to a good bank-bad bank [scenario]. Clean out the bad loans. I would encourage the banks and government to do that here. The drip test of putting good money after bad money never pays off. You’re compounding the issue,” Kravis said.

“Today, that is dramatic and needs to be done. If that is done, the banks can raise real capital to replenish the hole in their equity base and start lending again. Right now, everybody’s frozen and that’s not good for any country. Somebody says to you we have only 5% NPL, but I don’t know whether it’s right. I’ve seen everytime a bank says it’s not that bad, it’s much worse. Everybody wants to push it [the problem] under the rug and hope it gets better, but it doesn’t.”

Kravis said the government or the banks themselves can set up such ‘bad banks’, so long as the NPLs are off the banks’ books. “Banks in India don’t act as investment banks. Kotak does, but that’s about it. In the West banks are both banks and investment banks,” he added.

Sanjay Nayar, member and CEO of KKR India, who was also present at the meeting with journalists, added that while the prompt corrective action (PCA) mechanism for weak banks introduced by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) was a “stop-gap measure”, the banks would eventually have to be recapitalised. Adding to Kravis’ point on setting up ‘bad banks’, he said: “There’s no point putting more government money behind a muddled up balance sheet. Another $25 billion won’t make any sense unless you know what hole you’re filling up. After the May elections, the new government will have to take this problem head on.”

Kravis, however, said that despite the NPL problem, India had moved forward on a number of areas, chief among them being the introduction of a bankruptcy law and putting in place a goods and services tax (GST) regime.

On the differences of opinion between the government and the RBI, which eventually led to the resignation this week of the RBI governor, Urjit Patel, and the appointment the very next day of former bureaucrat Shaktikanta Das to replace him, Kravis said there was “nothing new” in governments trying to “jawbone” central banks.

“I laugh about [it]. Right now [U.S. President] Trump is yelling and screaming at the head of the central bank. He’s a pretty important guy and he’s raising interest rates. Trump is in a panic over this,” he added. “Central banks in most countries are independent and they have to be independent. They’ve got to be able to do what in their view is the right thing for the growth of the economy, slow down an overheated economy if that’s what is needed, slow down inflation...”

Speaking about KKR’s India operations, Kravis said getting Nayar, a former CEO of Citi in India, to head the India office in 2009 was “the best decision we ever made”. KKR, he said, was a firm which thought and acted like industrialists and that is why it could understand the needs of entrepreneurs who they partnered with in companies. Kravis said the firm was one which “bought complexity and sold simplicity” and while it had started off globally as a pure-play PE firm, today it had morphed into a “solutions provider for companies” which was not only into buyouts but also into managing multiple alternative asset classes, including energy, infrastructure, real estate and credit, with strategic partners that manage hedge funds.

“Earlier we used to be mainly a PE firm. We would walk in and ask the owner, is your company for sale? And if it was not, the conversation would end. Today, we get to know him, his company, and find out what he needs. We could provide equity, credit, take minority or majority positions, and help with real estate and even make acquisitions for him. That’s where KKR has positioned itself,” he said.

On KKR’s learnings from India, Kravis said in the initial years, the firm had taken a lot of minority positions in firms when it didn’t have the influence it had hoped to have. “One of our biggest learnings is we’ve been taking positions. We haven’t had the same control as we would have in a control situation. Second, and we can’t do much about it, we invest in dollars and that [the rupee fall] has killed us. You have to factor that in.”

Nayar added that since KKR was the last major PE firm to enter India, the minority positions were needed as “growth wheels” to establish the brand. But even there they chose the correct partners. The later investments have all been with either majority control, or significant minority with clear alignment with the entrepreneurs, he said. Indian promoters, Kravis and Nayar said, were now much more willing to cede control. The need to move to a quick solution outside of the National Company Law Tribunal mechanism in cases were companies were facing problems was also one big reason why KKR was seeing major opportunities in India at this point.

KKR India has recently strengthened its India team further, appointing two new directors in its credit business. It had also recently hired Ananya Tripathi from online fashion firm Myntra as director in KKR Capstone India, the entity which assists in value creation for KKR India portfolio companies. KKR India has two NBFCs in India, one for credit and another for real estate, and has invested over $7 billion in credit in India. Among KKR’s portfolio companies in India are Bharti Infratel, Coffee Day Resorts, Avendus, Max Financial Services, and Radiant Life Care.