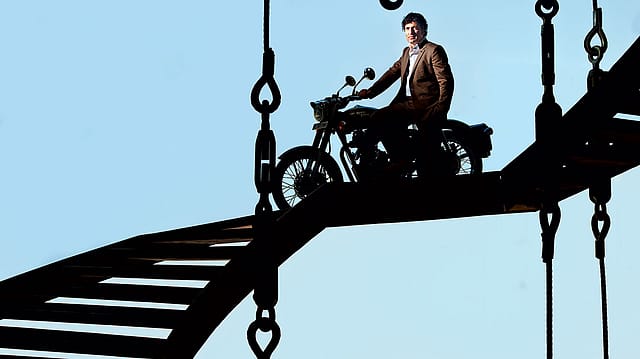

The talented Mr. Lal

ADVERTISEMENT

Dressed in worn jeans, checked shirt, and buckled leather sandals, Siddhartha Lal, 37, cuts an unlikely picture of a business tycoon. It may be Saturday morning; however, he is lugging around a rather formal leather portfolio and has a business meeting later.

He chooses to meet at Latitude 28, the café on the first floor of the Goodearth store in Khan Market, a hangout for upwardly mobile shoppers and diners in Delhi. The Good Earth chain is run by his mother and sister, and stocks high-end home accessories and natural or organic food. Lal has many business discussions here over cups of green tea—he feels at home. He is the third generation of the Delhi-based Lals who made India’s first indigenous tractors in the late 1940s, tying up with Germany’s Eicher. Has he shed his long, curly locks to look more businesslike—as the CEO and managing director of Eicher Motors? “I don’t remember when I had a haircut. I go to a hairdresser maybe once in two years, and end up cutting it on my own more often,” he responds.

Cool dude? Perhaps. But start talking business, and the image fades quickly. Eicher Motors, which makes small trucks, buses, and motorcycles, saw its valuation increase seven times in the last three years, even as that of biggies such as Tata Motors and Ashok Leyland have stagnated. Eicher’s joint venture with Volvo will manufacture new truck engines that will comply with the latest global emission standards, a move that will bestow a clear technological edge over the competition. Royal Enfield classic motorcycles from Eicher’s two-wheeler division, India’s answer to Harley Davidson, which cost Rs 1.2 lakh each, now have a nine-month waiting period. Eicher’s investment to trigger the big spurt in the firm’s valuation in the last three years—nothing.

In a little over half a decade, Lal has metamorphosed from a biker-at-heart who took the challenge to save his inheritance, to a shrewd deal maker with uncanny business instincts, running a Rs 4,700 crore automobile firm.

The signs were always there. He turned around the Rs 150 crore Royal Enfield business in the late 1990s, when he was in his twenties. He invited a few friends who were passionate bikers like him to build a young, new management team at Royal Enfield and change the way the bikes were made. He sold factories, rationalised products, and hired auto journalist Sachin Chavan, an Enfield fan, to popularise the brand through biking communities and the like. The leadership of the entire group was handed to him in 2006.

Eicher is still relatively small. But Lal’s clout comes from the fact that he is finally a formidable player in commercial vehicles, considered a big boys’ club in India. Then there’s the latent potential of making it big with Royal Enfield. A. Ramasubramanian, who worked with Lal in Eicher, and is now CEO of heavy-duty truck maker, Asia MotorWorks, says, “Though we don’t compete with it, Eicher is certainly on everyone’s radar in the commercial vehicles space with its Volvo tie-up.”

Lal is doing more than merely securing a future for his firm. With his firm’s market capitalisation at a historic high of Rs 4,330 crore, he’s talking a new language. “Earlier, our aim was just to make money, stay afloat. It’s now about creating value for stakeholders.”

His confidence comes from the way Eicher’s value has jumped. Ten years ago, it was Rs 46 crore. Three years ago, about the time the Volvo deal was inked, it was Rs 660 crore. Ajay Parmar, analyst at Mumbai-based research firm Emkay Global Financial Services, says if Eicher continues to sell more trucks, squeeze better margins and its engine business gets going, there’s a good chance for its price to accelerate when the markets turn. “Its current valuation is more or less based on its performance but if the market puts a sale price on the business, the company will be worth much more.” And Lal family seem to be on track to becoming dollar billionaires soon.

AN ECONOMIC GRADUATE FROM Delhi’s St. Stephen’s College with a master’s degree in automotive engineering from the University of Leeds, Lal didn’t want to spend time studying for a management degree. He rolled up his sleeves and got down to do the dirty work at Royal Enfield, even roping in his friends to help.

After he took the helm of Eicher, he shrewdly played his cards to unearth the latent value of his company. Around then, India started building its national highways, and the trucking scene began to change. The need for more powerful and reliable trucks and faster turnaround times lured the big international players to rethink their businesses here. Most firms wanted an Indian partner to help them handle sales and after-sales. Eicher was a prime candidate—it was a small player, with limited technology. Further, it lagged behind leader Tata Motors in every business aspect—size, profitability, and technology.

Lal got the Boston Consulting Group to help figure what businesses the company should retain and what it should give up. The tractor business, Eicher’s oldest, was sold, to “cut losses”, prompting old-timers to believe that Lal would eventually sell everything and quit. That he wore his inheritance lightly unlike other scions, dressed in jeans, and grew his hair didn’t help either.

However, Lal held on to the truck and bus businesses. But that decision was tested in 2006, when Tata Motors launched aggressively priced products to compete with Eicher. A former colleague, who now works for a competitor, says: “This was Siddhartha’s moment of reckoning—he had a chance to change the course of history for Eicher.”

Every company in global trucking met Lal. As foreign trucking giants such as Mercedes, Paccar, and Volvo solicited partners, Lal was among the minority willing to have an equal partnership. He had few options then. Eicher was a weak player, present only in the small, highly competitive, light commercial vehicle segment. (The Tatas weren’t interested, while the Hindujas of Ashok Leyland had made it clear that if they partnered, they would want control of the business.)

Lal spent a lot of time in Stuttgart, Germany, at the headquarters of Mercedes-Benz. (Eicher had then denied it was in talks with the German auto maker.) The deal fell through at the last minute. Mercedes wanted control and would not agree to the valuations Eicher wanted. In hindsight, it might have been the best thing to happen to Eicher.

A senior Volvo employee says his company was constantly in touch with Lal even as he was negotiating with Mercedes. Volvo had been in India for nearly a decade and had a meagre market share as it sold heavy-duty trucks with limited applications in India. Further, it had struggled to set up a dealer and after-sales network and had high overheads. A close associate of Lal’s, who was part of the negotiation team, says Volvo’s management wanted the deal only with Eicher.

Instead of investing directly in Eicher, Volvo accepted the creation of a separate company that would be a subsidiary. Thus, Volvo Eicher Commercial Vehicles (VECV), the joint venture, was born. Volvo’s 49-tonne trucks would continue to be assembled by Volvo India, its 100% subsidiary and then transferred to VECV, which would handle the distribution and after sales. Volvo also paid Rs 1,082 crore for its 44.6% stake in VECV. It then took 8% for Rs 157 crore (at a substantial premium to the market) in Eicher Motors, to effectively own a 50% stake in VECV. Overnight, Eicher’s valuation jumped on account of the new cash and the potential new growth benefits from the Volvo collaboration.

Eicher, on its part, transferred its commercial vehicles manufacturing facilities, which made trucks and buses, to VECV. Royal Enfield continued to be a part of Eicher. “There was an immediate cultural fit that drew us to Volvo,” says Lal.

Three months after both companies signed the letter of intent for the venture, Jorma Halonen, Volvo’s high-profile deputy CEO, who also headed the Chinese trucks business, retired prematurely in early 2008, ostensibly to lead a slower life. According to senior Volvo execs here, Halonen’s exit was abrupt and there was no customary advance mail to global team members. Halonen has recently joined the board of India’s No. 2 commercial vehicle company, Ashok Leyland.

Halonen was quickly replaced by Par Ostberg, the then chief financial officer, who was part of the team that worked on the Eicher deal. He is now the president of the Volvo truck business in Asia and VECV chairman. Ostberg, who is also senior vice president and member of Volvo’s executive committee, says: “The deal with Eicher happened quickly because we felt connected in several issues, ranging from strategic to skills.”

Soon after the joint venture began, Lal realised that Volvo was scouting for a location in the emerging markets to make its new 160 hp to 300 hp engines for light and medium trucks. He then suggested to Volvo that the engine could be made through the Indian joint venture. His sweetener: With frugal Indian engineering skills, they could get good returns from exports. As VECV would put up the initial investment of Rs 450 crore, Volvo signed up last year to make and outsource the engines from India.

While the 300 hp engines qualify for medium-duty trucks in Europe and other advanced markets, in India manufacturers made heavy trucks above 25 tonne payload with these engines. The usage was peculiar, driven by fuel efficiency and lack of technology. Tata Motors and Ashok Leyland managed for over a decade by tweaking a single engine of about 200 hp to power their trucks. Ashok Leyland has spent three years on a Rs 750 crore plan to develop Neptune, its new range of 300 hp to 325 hp engines that will fire its future trucks. However, about 70% of all commercial vehicles sales come from trucks that sport 160 hp to 300 hp engines.

THE DEAL BROUGHT LAL some more benefits. Months after it was signed, Lal wrangled a concession. He could now use some of the engines VECV was making for Volvo on Eicher’s own heavy-duty vehicles in India. (Remember, so far the engines were just for exports). This was a masterstroke—for over a decade, Eicher had struggled to get its engines right.

It had first showcased its heavy-duty trucks at the 2000 Auto Expo but sales dwindled to a few hundred two years after the launch. Reliability was the big problem. Eicher relaunched the trucks in 2008 with the Volvo engines, and is continually taking tips from Volvo to fine-tune the product. Last year, Eicher’s market share in the heavy-duty segment doubled from 1.7% to 3%. Lalit Malik, Eicher group’s chief financial officer, says: “We expect our volumes to multiply 10 times in the next four years in the heavy-vehicle segment.”

VECV’s initial mandate was to make 85,000 engines, largely for exports to France and Volvo’s other manufacturing centres around the world. The number has since increased to 100,000 by 2015, though around a fifth of these engines will now be fitted on Eicher trucks made by VECV. The icing on the cake—Volvo’s engine will be compliant with Euro 5 and Euro 6 emission norms that won’t be applicable in India until 2015. In a deft move, Lal has sorted out Volvo’s problem and got himself technology that will put him ahead of Tata Motors and Ashok Leyland and on par with new entrants such as BharatBenz, Japan’s Isuzu Motors, and Sweden’s Scania. “In some years, big Indian firms won’t be able to pin us down on price,” says Malik.

Talks are also on to assemble marine and industrial power engines for Penta, and aviation engines for Aero, two businesses that are run by Volvo India. In other words, VECV will slowly become Volvo’s engine shop here.

The joint venture is also spending money to completely overhaul one of the three Eicher manufacturing units in Pithampur, Madhya Pradesh, that will make gear boxes for its trucks. Volvo has also initiated several moves to help Eicher improve its vehicle quality and its service outlets across the country.

Recently, the company inaugurated Apco Autosales, a 36,000 sq. ft. dealership in Rajkot, Gujarat, which will use contemporary methods for sales, service, and spares. A team from the dealership underwent training at Eicher Training Academy in Pithampur, which drew inputs from Volvo’s international expertise. Vinod Aggarwal, VECV’s CEO, says: “While Volvo and Eicher will keep their brands separate, there will be uniform standards in dealing with customers.”

Volvo has provided Eicher with technology to build rear-engine and low-floor buses, the new choice of several states for urban transportation. Eicher recently won its first government deal—400 buses from Andhra Pradesh State Transport Corporation—on the back of this new technology. Then, Volvo helped it develop a new 6x4 tipper used for mining and also another medium-duty truck.

At the moment, Volvo is happy with its arrangement with Eicher as the venture is raking in the cash. But the key question is, will Volvo ever launch trucks that directly compete with Eicher’s trucks that VECV is selling? Mercedes, for example, will launch its trucks with payloads between 4 tonne and 40 tonne. Lal says it is early days and that the joint venture is still in startup mode. “Right now, we realise that the commercial vehicle business creates the value for Eicher and it makes all the more sense to put all the might behind the joint venture.” He adds that if and when Volvo chooses to launch similar capacity trucks, they will be more premium than what Eicher now sells.

But here’s one of the little-known aspects of the agreement between Lal and Volvo. Eicher has a put option to cash out of the venture if it so chooses. It is possible that Volvo has a similar option, though it couldn’t be independently confirmed.

Volvo is bullish about the joint venture. Ostberg says, overall, the company is happy with the way its Asia business is progressing. From less than 5% in 2006, it has grown to nearly a quarter of its global turnover now. Volvo has three expectations from the Eicher venture—develop Eicher’s range of products in India, make India a base for its heavy-duty engines for different applications, and develop a global supplier network to plug into the rest of the Volvo group worldwide.

“In any case, we are 50% of a joint venture that will make a lot of money,” says Ostberg. “We are happy with it for now. Of course, we can’t predict the future.”

LAL HAS STARTED SPENDING more time with his other business, Royal Enfield, which has been making bikes for the last 60 years. There is an ongoing expansion in the already packed Chennai factory to raise the capacity from 70,000 bikes to 100,000 bikes a year. Last month, Eicher announced it was setting up its second factory on 50 acres on the outskirts of Chennai. This factory will sport the same paint shop used by Harley Davidson’s factory in Milwaukee. There will be tours for customers, who will now be allowed to customise their bikes, buy merchandise, and lounge at a café in the factory.

Venki Padmanabhan, Royal Enfield’s CEO, says: “Right now, we are just supplying to latent demand, but at some point, we will compete with global brands that are lining up, such as Harley Davidson and Triumph.”

A lot has already changed. The leaky, cast iron engine, which in the past added to the Enfield experience, has given way to a more reliable, computer-machined aluminium engine. There is more modern stuff in the machines, such as electronic fuel injection, to appeal to a newer audience. More changes are on the way. Today, Enfield fuel tanks are hand assembled and one in a thousand invariably leak. In the new factory, these will be machine made.

Padmanabhan says Royal Enfield bikes have a huge export potential not just in developing markets but also in western Europe and America, for their classic value. They sell alongside Triumphs in Britain at a substantial premium to the Indian price. He adds that Lal is already thinking of the day his competitors will start making products cheap enough to compete with Royal Enfield, just as European and American car makers have designed low-cost, small cars for India.

Today, Royal Enfield’s Rs 500 crore revenues are small, but Padmanabhan says it is more profitable than others. “We are the leaders in a niche and we are looking to expand that leadership to other geographies slowly,” says Lal. .

With the two businesses set in rhythm, Lal says he now feels a little free to look beyond them. He wants to invest Rs 500 crore, a great deal of money for the Eicher group, which has not made any fresh investment in the last few years. He is not disclosing anything yet, but says that he is interested in urban and mass transportation. A close associate says there are several niche areas in the segment that can give the big returns Lal has now come to expect of his investments. He may well be the auto entrepreneur to watch for.