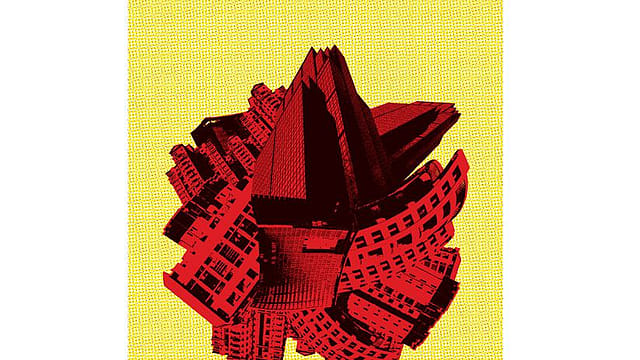

The secret disease ailing India Inc.

ADVERTISEMENT

There is a secret that no one in Indian business ever talks about openly. That secret is this—a large part, some would argue most, of Indian business is run on what one could call ‘information arbitrage’. That is a polite way of saying projects are, often, won through manipulation rather than competition. It is who you know, what information that person shares with you, and when, that determines the fate of your bottom lines.

Now, one could argue some of this happens in every part of the world, but rare is the place where it has been turned into a fine art over 70 years as it has been in India.

One could argue that the early focus on socialism distorted the system but in fact the problem runs deeper. There are two parts to the problem. One is an innovation issue. Take the automobile manufacturers in the country. Some of the poorest quality cars in the world are mass produced in India, and that industry should be pushing for a complete shift to electric vehicles seeing the murderous air pollution rather than trying to stall the change. The other is persistence of an insider network of ‘family and friends’ that hinder competition, put up insurmountable entry barriers and prevent the cycle of creation and destruction of businesses in India.

January 2026

Netflix, which has been in India for a decade, has successfully struck a balance between high-class premium content and pricing that attracts a range of customers. Find out how the U.S. streaming giant evolved in India, plus an exclusive interview with CEO Ted Sarandos. Also read about the Best Investments for 2026, and how rising growth and easing inflation will come in handy for finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman as she prepares Budget 2026.

A whole range of companies, and their wily founder-owners (one of whom, along with his wife, was trying to fly off to London, leaving behind the wreckage of a company and massive unpaid debt, when they were stopped by authorities in the nick of time) could thrive only because they were able to incessantly manipulate the system, and ensure that they could bend government rules to favour them.

This is the kind of thuggery that nearly destroyed the Indian real estate sector, the washing machine of Indian politics, where every rupee from dark deeds could inevitably emerge as white until the recent collapse. The pyramid scheme which was being run beautifully by business people and politicians has come crashing down, at least in real estate. Most homes that are sold in India are wildly overpriced, not least because the cities they are in are fundamentally foul to live in. This system worked as long as easy cash kept coursing through the system—prices would always rise, there were always buyers at ever higher prices, and everything from land prices to delivery schedules were scammed. And there was always a public sector bank to foot the bill. All it took was a phone call from a politician. Why innovate, why price competitively, why even compete when you could cheat?

A perfect storm is destroying this system slowly but surely. Digitisation is chipping away at some of the customer-facing information arbitrage. Some of the worst offenders in politics are no longer near the highest seats of power. And many Indian customers are refusing to buy shoddy cars and pitiable properties at high prices. As digitisation raises confidence in rental contracts, more and more millennials will see owning a home as a waste of cash just as they now see buying a car.

But the core attributes of mistrust and inward-looking-ness in India’s business climate will take longer to heal. It is a societal issue that goes back at least a couple of hundred years. Let me explain.

As the economic historian Tirthankar Roy explained in The Cambridge History of Capitalism, ancient Indian merchant groups had both kinds of formations—those based on kith and kin, and those purely based on professional engagement.

But the arrival of colonialism turned the gaze of Indian business in many ways inwards, making them insular. The English East India Company also brought in, with its very large purchases, advance contracts of a kind that Indian business had not experienced in large numbers before. This led to many a dispute and as colonial rule and law grew stricter, so did the inward-gazing of business communities here.

“Institutionally speaking, colonialisation had an ambiguous effect upon the business community. The cohesion of kin-based groups had earlier depended on the king as a guarantor of the judicial autonomy of business communities. The company state unwittingly made this guarantee weaker than before by creating new law courts with the power to override community rules,” writes Roy.

“The great paradox of colonial legislation in India was that it adopted a dualist principle to begin with—English common law for Europeans, and by default, communal-religious law for Indians. As a result, while these courts could test and challenge juridical autonomy of the community, the courts also displayed a bias for settling cases in favour of the Indian tradition. Strengthening collective bonds was one of the strategies that individuals adopted when entering unknown forms of enterprise, or transacting with unknown people.”

What was once a colonial response mechanism then grew into one of the most vicious insider networks in the world, aided and abetted by the government for 70 long years.

It is the cleaning of this system that lies at the heart of reforming Indian business. This is an act of spring cleaning which will cause great pain before it leads to a better, more innovative dawn. Expect several so-called giants of Indian business to collapse before a range of sharp, competitive new companies replace them. This is not merely about Indian business but also about a reformation of the nature of trust in Indian society.