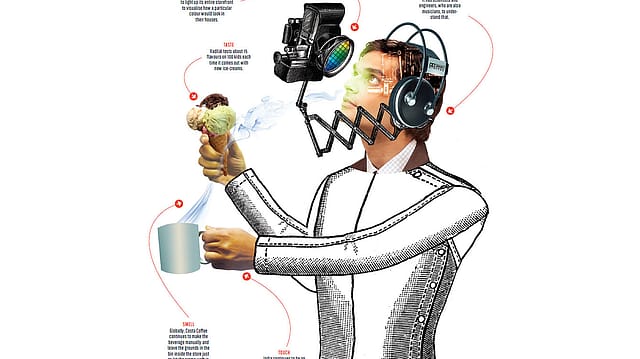

Making business of senses

ADVERTISEMENT

FOR THREE YEARS, the “lack of music” in outlets consistently topped customer feedback at Costa Coffee in India, which started operations here in September 2005. “A survey by global consumer research firm GfK NOP across 12 countries revealed that people here chose their coffee shop by the music it plays,” says Santhosh Unni, CEO, Costa Coffee India. An in-house radio service called Costa Radio, the only one of its kind for the British beverage chain, was launched soon after. Since then sales have increased manifold, and Costa has had the fastest expansion in the country the last three years—it added 65 outlets, the 100th just five months ago. It now plans to have the 200th store in the next two years.

The way it works for the consumer, says Anirban Chaudhuri, an independent brand consultant and former senior vice president with DDB Mudra and Dentsu Communications, is that one can have coffee anywhere but the customer expects a certain experience during a certain time of the day. “Sensory branding helps you live that. The cup of coffee will energise you, but there needs to be a certain kind of lighting, colour, and music, to enhance that experience. And after a day’s work, you would like it to be more relaxing. It need not be the recipe [for the coffees served] all the time, it is also about the ambience.” Costa Radio changes the genre of music for morning, afternoon, and evening.

Before Costa, there was Westin Hotels, which played its signature music to welcome guests. Bakeries around the world build their identities with the distinct aroma of vanilla, fresh cream, and flour wafting through the surroundings. And then there is Singapore Airlines, which in the 1990s, created an in-house fragrance called Stefan Florida Waters. The staff would wear it, hand out wet towels with the perfume before boarding, and spray it in the cabin. The aroma is so distinct that passengers recognise the airline blindfolded. (Stefan Florida Waters has never been retailed.)

January 2026

Netflix, which has been in India for a decade, has successfully struck a balance between high-class premium content and pricing that attracts a range of customers. Find out how the U.S. streaming giant evolved in India, plus an exclusive interview with CEO Ted Sarandos. Also read about the Best Investments for 2026, and how rising growth and easing inflation will come in handy for finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman as she prepares Budget 2026.

Back home, with rapid socioeconomic changes following de-licensing in the early 1990s, and with recent economic expansion, new markets are being created and existing ones expanded. It is estimated that over 300 million people will advance from the rural poor category to rural lower-middle class by 2025. Overall consumption levels are also expected to rise. Chasing all these consumers is a surfeit of brands, jostling for market share. And one distinctive way to stand out—stimulating as many human senses as possible. Little wonder then, that companies are raising R&D budgets and hiring specialists to address all the five senses.

and Darshan Gandhi, associate vice president-design, Godrej Consumer Products, with samples of Aer.

“The business of senses is fast moving from being auxiliary to being the growth driver for consumer goods companies here,” says David Blair, managing director-South Asia, Fitch, a British design studio. From two multinational manufacturers that catered to the senses a decade ago, India is now home to about eight. The world’s largest fragrances maker Switzerland-based Givaudan, U.S.’s International Flavors & Fragrances (IFF), and Symrise of Germany are among them. Fitch has 60-plus employees in Delhi and Mumbai, from just one when it started in 2007. This apart, there are 10 domestic companies. Chaudhuri says there was an era when people talked about products, then they moved on to consumer centricity or services, and now the talk is about experiential marketing, with emphasis on the five senses.

THREE MONTHS AGO, global private equity giant Blackstone picked up a 33% stake in India’s largest speciality fragrances and flavours maker S.H. Kelkar & Co. (SHK) for Rs 243 crore. It wants to cash in on the human senses on which SHK has built its business over the last eight decades. The investment marks the PE company’s entry into the niche aroma and flavours market. SHK serves some of the country’s biggest consumer goods companies, such as ITC, Marico, and Emami, and has a strong presence in West Asia and North Africa. “Olfactory, auditory, and visual are the three areas where you see a lot of work happening, especially in retail. It is true of India as well,” says Chaudhuri.

Flavours and fragrances is a Rs 2,000 crore market in India and growing annually at 10%. With foreign direct investment allowed in retail recently, the sector gets a leg-up. “Globally, fragrances and flavours is a high-growth industry, especially in Asia, due to accelerating personal consumption,” says Amit Dixit, senior managing director, Blackstone India. SHK is the only Indian player with scale and is uniquely positioned to capitalise on this opportunity, he adds. “[Also,] Blackstone has been focussed on domestic personal consumption as an investment theme and SHK was an excellent fit.”

Multinational manufacturers alone control about 80% of the domestic flavours and fragrances market, and they are expanding. IFF opened a new factory in Gurgaon, near Delhi, six months ago, and has beefed up its Mumbai centre. Its local operations, which have grown at 15% to 16% annualised for five years, generate more than 3% of its global turnover of $3 billion (Rs 16,638 crore). Similarly, when Givaudan in October confirmed that emerging markets constituted 43% of its global sales, and growing demand there helped it offset the slack in Europe, India was at its heart. It is almost the same with digital sound and visual art companies.

TALKING ABOUT SENSORY experiences, Chaudhuri says a large part of it here happen in the packaging of consumer goods. He points to a pack of Knorr soup from Hindustan Unilever Ltd (HUL). “The pictures of vegetables on the pack have a glossy feel, while the rest of it has a matt finish. The smoothness brings out the fresh feel,” he says.

Prabuddha Dasgupta, former head of packaging at HUL, says it works the same way as a bottle of water which is always perceived as clear. “A person judges its purity by the transparency. It also conveys that the water is fresh,” he adds, pointing to the reason why water is always packaged in transparent bottles. Equally, ergonomics matters, says Dasgupta, so “you can hold it [comfortably] to your mouth to drink from it, and also have the right shape to store it in your fridge”. A complete sensory experience is thus created.

When Godrej Consumer Products (GCPL) launched its air-care brand Aer, and redesigned the packaging of its 60-year-old personal care brand Cinthol for Rs 60 crore three months ago, the emphasis was on both look and feel, keeping with the company’s new design philosophy: unclutter. A room and car freshener, Aer went through the usual scrutiny—three fragrances were chosen after experts at GCPL sniffed up to 1,000 fragrances a day for six months. But from its experience of distributing AmbiPur in India, till P&G took over the brand, and having bought Megasari, an air-care leader in Indonesia, GCPL knew it was not just about having the right fragrance, “Aer needed to look and feel just as good,” says Darshan Gandhi, AVP, design and innovation, GCPL.

Hardik Gandhi, creative head of Design Gandhi, a home-grown design studio, which created the Aer branding, first addressed the entire range as one family and not separate products—he made circular design its uniform and key aspect. Second, he used functional packaging. The car perfume bottle meant for the cup-holder can be twisted with one hand to release the fragrance, while the device for the AC vent has a push-button start-or-stop function.

“The push-button is a key input, as it was the result of several studies, which found that the range selector (in AmbiPur) was inconvenient. Most customers wanted a way to start or stop the fragrance at will,” says Hardik Gandhi. The design tweak has also added to the life of the perfume, which can run upwards of 60 days, he adds.

"ASK, ASK, AND ASK,” says Dasgupta, explaining how some of the sensory developments came about. He recalls a time when HUL designed a new water bottle, and gave it to a customer to test. The customer approved, but HUL officials asked him to take it home. “We kept the bottle in his house with a camera on to see how his child adopted it,” says Dasgupta. The child struggled with the bottle, and HUL scrapped the design. Nilanjan Bhattacharya, COO for India and SAARC, Barista Lavazza, a coffee chain, says one of the alterations they made after observing customers was in the way food was displayed in the outlets. “Barista uses display units where the lighting makes fresh food look fresher.”

Nearly 100 children between the ages of 8 and 10 test ice-cream maker Vadilal’s products. “Around five of the shortlisted 15 flavours are rolled out after each exercise,” says Devanshu Gandhi, managing director, Vadilal. Even factory staff gain 5 kg to 7 kg during tests, he says. Vadilal sets aside 1% to 1.5% of its total sales for R&D and buys flavours to mix and match for unique offerings, such as Pineapple Tamarind, Litchi Raspberry, Bubblegum Blackcurrant, Silk Chocolate, and Golden Ribbon. He adds that market research is periodically done to launch new products.

Customer behaviour also drives Asian Paints, India’s biggest paint manufacturer. This Diwali, the company allowed customers to light up the entire storefront of its 7,500 sq. ft. outlet on Hill Road, Mumbai, in a colour of their choice to visualise how it would look in their houses.

“We watched a person’s behaviour to see how we could create an experience around it,” says Blair of Fitch, which was roped in by the paint maker for the exercise. He adds how important it is in India, given the nature of its “unpackaged society”.

Before buying anything, Indians, he says, experience the real thing. A housewife will dip her hand in a sack of rice to feel its texture and then bring her hand near her nose to sense how it smells. Fitch has designed Vodafone’s stores and Godrej’s Nature’s Basket, a food chain, among others, catering to their distinct look, touch, and feel.

Chaudhuri says the consumer loves an experience and then goes on expecting that. “The sleekness started by Apple has caught on to not just handheld devices, but even TVs and other gadgets. Today, the touch phenomenon has become such a rage as an user interface that you won’t go back to something with hard buttons.” He adds that while creating a sensory experience, companies also look for ethnography—the understanding of culture codes—which differs from market to market, and across segments. “What red means in West Bengal and Kerala may not be the same elsewhere,” he quips.

Indian culture taught Costa that replicating the design of its most successful outlet in Britain was just not enough. “Unlike in Britain, we realised Indians like bright colours, prefer food along with their beverage, and stay longer,” says Unni. So Costa outlets feature loud greens as part of its decor, colour photos instead of the standard monochromes on the walls, and more cushioned chairs. Spices were added to English Shepherd’s Pie, and calzones came with a spicy Chettinad filling. A vegetable loaf tastes the same as a samosa. “Customers at Costa look for Western food, but want Indian taste,” Unni adds.

THE HUMAN SENSORY SYSTEM is sophisticated and subtle. They are not linear, and are adaptive to surroundings. Over 600 people at Dolby Laboratories globally (15 of them in India) are trying to decipher the science of uniting sound with sight. “Human perception evolves according to upbringing. The auditory senses of someone who grew up listening to iPods are quite different from a person who has grown up with LPs or CDs. It is, therefore, important for us to understand the changes, anticipate trends, and invent for the future,” says Michael Rockwell, executive vice president, products and technology, Dolby Laboratories.

Here, Dolby has audio experts, internally called “golden ears”, comprising engineers and scientists who are also musicians and content creators, who listen to what is good and bad sound in the Indian context. Pankaj Kedia, country manager, Dolby Laboratories India, shares an interesting finding. “There is this concept of loudness. Indians like loud content. When we dug deep to understand what it was, we found that people were seeking clarity. They want clear entertainment, they want clear sound. It wasn’t about ‘I want my ears to be blown off’. It is just that sometimes when things are not that clear, or well rendered, they think loudness will solve the problem.” This may have to do with the fact that India is generally a noisy country.

Direct-to-home content providers such as Tata Sky, Airtel, and Sun Direct use Dolby in their set-top boxes, and on average, the sound maker is closely associated with 200 to 300 movies a year across languages. “India is a big market for devices, content, and services. It also has a strong local content ecosystem—not just dubbed, but content generated in many languages,” says Kedia. That has led Dolby to provide mastering services to content creators that bring together various elements such as music, dialogue, and background score to create the soundtrack, he adds.

“Our engineers do studies and checks so that the soundtrack plays back right. See it from the perspective of a sound designer or a director—they spend months to make every small element work. The impact of the gunshot needs to be at the right moment and at the right level. The most important thing is that when people watch the film they get the right experience. If the experience were to change, so would the movie,” says Kedia.

A similar thinking is playing out in the automobile sector here. Says Abdul Majeed, auto practice leader PricewaterhouseCoopers: “Every original equipment manufacturer does a survey called the Voice of the Customer before launching a product, and they keep improvising based on the feedback. For instance, in the West, traffic is organised and use of the horn is minimal. But the way we drive here, we are far from achieving that. So, while keeping sound pollution in mind, auto makers have tuned their horns to be sharp, suiting Indian needs.”

So, Volkswagen has made its horns shriller, while BMW has introduced a module that takes the natural sound of the 4.4 litre bi-turbo engine to modulate throttle response from “comfort” to “sport plus” to boost engine growl. At Tata Motors, Timothy Leverton, head of advanced engineering, says, “A buyer perceives a vehicle’s quality from things such as the sound of shutting doors, interior noise levels, the plastics, and even the exhaust notes when idling.”

He shares, as an example, how the need for extreme quietness inside a car these days is driven by the fact that consumers connect their mobile phones to their vehicle’s stereo for conversation. “Engineers at Tata Motors have tuned the car’s entertainment system to deliver impeccable sound when connected to the phone, besides playing music. They have also ensured no part of the car rattles if bass music is played.”

Indulging the five senses, therefore, is only going north in India as the country finds its place among the world’s fastest-growing economies. Industry veterans Chaudhuri and Dasgupta predict that though the first round of spending was mostly in capital goods, the next round will be on personal consumption. Proof: Look at all the spas, beauty clinics, and fitness centres mushrooming. The business of ingredients only make sense.