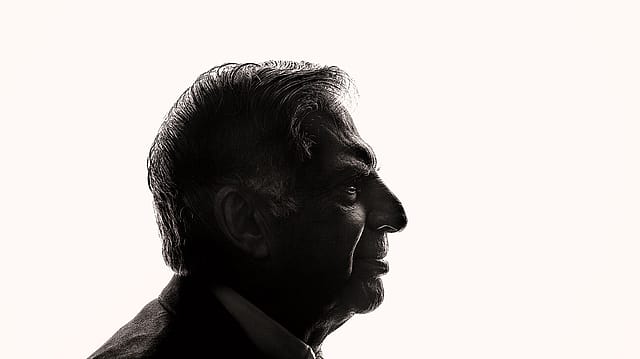

Ratan Tata logs in.

ADVERTISEMENT

The founder and ceo of online lingerie store Zivame, Richa Kar, wasn’t even born when Ratan Naval Tata worked in Noamundi in the early ’60s. The mining valley town near Jamshedpur is Kar’s hometown. To get there, she flies to Kolkata, takes a train to Jamshedpur, and then drives for six hours. It would have been more arduous when Tata did a stint at Tata Steel’s Noamundi outpost in the early ’60s. He says he loved it, for “the experience of being in a mining town with its own personality”. Five decades later, when Tata, 77, was in Bangalore early February for an investor meet, the town’s name brought an instant smile to his face. “I am delighted to connect with somebody from there,” he told Kar, whose father retired from Tata Steel’s mining division. “But for the Tatas, Noamundi would have been a pin code—not a town,” Kar replied.

Kar was among 60 invitees at a day-long event in Bangalore, hosted by the $350 million (Rs 2,211 crore) venture capital fund Kalaari Capital. He will serve as advisor to the founders of Kalaari’s portfolio companies, including Zivame, digital newsstand Magzter, online learning platform SimpliLearn, and biopharma research platform Vyome. The bigger deal of course is that Tata is turning investor in some of these ventures. In the past six months, he has made small investments in Snapdeal, BlueStone, Urban Ladder, and most recently, CarDekho. Fortune India’s ‘40 Under 40’ listing this year features founders of several of these ventures.

Ratan Tata stepped down from the helm of Tata Sons more than two years ago; rare public appearances like this serve as manna for Tata watchers rebuffed by his fabled reticence. And so, when he steps into the thrill-a-minute world of e-commerce, the media laps it up. The headlines around Tata’s love for the sector predictably serve to amplify the thrill. “Has Ratan Tata Chosen Wisely?” asks pink paper Business Standard, before attempting to slot his investments into “rash” or “far seeing” based on their profit potential.

January 2026

Netflix, which has been in India for a decade, has successfully struck a balance between high-class premium content and pricing that attracts a range of customers. Find out how the U.S. streaming giant evolved in India, plus an exclusive interview with CEO Ted Sarandos. Also read about the Best Investments for 2026, and how rising growth and easing inflation will come in handy for finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman as she prepares Budget 2026.

Think again: Online retail is, after all, just 2% of the total organised retail market, and by all accounts, the profit question around it is not specific to Tata’s choices. Also, Tata comes into the picture only after his crack team has already approved the investee companies. He meets his companies once every two or three months at his Mumbai office, and spends most of the time listening to them rather than holding lectures. He obviously thinks highly of his investees, but that doesn’t mean he will dole out doting quotes on them. (He declined to speak to us for this story.) Not for him the mantle of the hands-on investor omnipresent in the aggro-fuelled world of startups. Tata’s real value is in fact exactly the opposite of all this: He is the voice of quietude in an industry recklessly obsessed with noise. All those breathless ideas about how the Tata name will transform the way upstart entrepreneurs are viewed in this country—the man himself would likely give them a wide berth.

Still, by late last year, it was the thing for some dotcom entrepreneurs to fly to Mumbai, cab it to Tata Starbucks at Fort in South Mumbai, climb up, wide-eyed, to the first floor office, and attend sessions with Tata. They say meeting him is very different from meeting a Silicon Valley legend, something that venture capital investors generally facilitate. Tata is something else. “He stands for so many other things beyond his own impact as a businessperson,” says Vani Kola, managing partner, Kalaari Capital. “It is about the heritage he comes from—and the impact the Tatas have had on India.” She is referring to the Tatas’ storied influence, backing industries ahead of their time—steel, hydroelectric power, chemicals, aviation, automobile, and

IT outsourcing.

Given that range, Tata is a dream mentor. “[But] you don’t pitch to him directly,” says Amit Jain, co-founder and CEO of Jaipur-headquartered CarDekho. “He only meets founders once the investment is finalised.” Typically, bankers on both sides first meet to discuss an information memorandum. This includes a view of the company’s business model, its market, how it will scale up, and so on. Tata enters the picture only after the investment is finalised. And when he does, he comes across as a pupil seeking to improve his own understanding of each individual business, never someone who has all the answers.

He finds the digital life enormously appealing, “but am I digitally wired? No, I think I have a lot of short circuits in my system,” he told Magzter’s CEO Girish Ramdas. “If we were sitting here maybe 10 years ago, I would have said I am at the forefront of the digital world at that time,” he said. These days, he says he is unable to keep up. He uses an iPad and iPhone. “They don’t help me type with two fingers as I [usually] do. I crave for a situation where there can be a good voice-to-text conversion that I can depend on. When I use the cellphone, I probably use 5% of its capability, because if I honestly make a commitment to get to know it better, there is a new product out in the market that I have to learn [all over again].”

On the sidelines of the event in Bangalore, I got to chat with him about what he makes of the Internet gold rush. “I am just a few months into this,” he said. “[The Internet] is clearly where the opportunity is, if you see how evolved online businesses already are in India.” It’s a disarmingly uncomplicated worldview, almost unfashionable if you consider the reams and reams of expert commentary churned out on the web every day.

Rather than the internet’s mythical allure, or valuations and market share, Tata buys into the entrepreneur’s leadership and the core philosophy of each business. None of the investments so far are category leaders. “There is a long way to go for the [e-commerce] category itself,” says Urban Ladder’s co-founder and CEO Ashish Goel. Like Goel’s company in the unwieldy furniture space, BlueStone and CaratLane are still fighting it out to establish the online jewellery market. Meanwhile, CarDekho is up against CarTrade and Carwale, the oldest auto-classifieds players. But at the heart of these companies is the emphasis on building engaged user communities, signalling Tata-esque focus on longevity.

At Snapdeal, headquartered in Okhla, founders Kunal Bahl and Rohit Bansal have pioneered an online platform for small- and medium-sized merchant businesses since late-2011. The network is said to touch almost 100,000 merchants, and Bahl is building a reputation for developing a win-win business model for his suppliers, Snapdeal, and of course the end customer. Tata wrote Snapdeal a cheque in August 2014, at a time when global investors were lining up to back competitors Flipkart and Amazon.

Indeed, Tata relates to such subtle, specific values central to each venture. Friends and associates talk of his love for design. And Urban Ladder’s design focus suits the man who did a stint with Charles and Ray Eames, renowned for their 20th century American architecture and furniture. Also on the list: innovation (BlueStone as a customisable jewellery brand built from scratch) and trust (CarDekho for its ability to build enough credibility online to tilt users into making a car purchase).

A nuance that is often obscured by the e-commerce-centric narrative of Tata’s investments is that he has carefully chosen industries where he developed a unique point of view during his years as an active global executive. Look at BlueStone in the context of Tanishq, Snapdeal in the backdrop of Westside and Croma, or CarDekho in light of his knowhow of building markets for the Indica and Nano.

“He knows more about jewellery than I do, having built one of the biggest Tata brands in Tanishq,” says

BlueStone’s Kushwaha. Ironically, Tata Sons resisted Titan’s diversification into the jewellery business. Xerxes Desai, then managing director of Titan, persisted, and Tanishq, born in 1996 during an economic slowdown, grew into an incredible success. It taught Tata to back the entrepreneur.

Belief apart, entrepreneurs say Tata is incredibly inquisitive. Sample his questions to the CarDekho founders. ‘How do you ensure that the car a user is about to buy is safe?’, ‘How do you engage endusers enough to keep them buying?’ and so on.

“He listens a lot before he speaks,” says Jain. “It’s very rare that a man of his stature would listen to us for so long. He asks a lot of questions even when we explain, and comments only after we are done.” Tata’s poser to CarDekho: ‘Can you take it to other developing markets?’ echoed a latent plan the founders have had since last year.

With BlueStone, he is interested in how jewellery designs are rendered and personalised online using technology, without requiring every product to be manufactured. His questions tend to probe how the Internet allows businesses to be leaner. “He likes our zero-inventory or low-inventory model,” says Kushwaha. “We are lean on working capital. This is distinct from [the offline model where] crores of rupees are spent in manufacturing and sale in multiple outlets. He appreciates that.”

The influence of the legendary J.R.D. Tata looms large in the love for questions. Tata said as much in an interview to Fortune India in February 2011: “As young officers, we’d have what we thought was a great idea, we’d talk among ourselves, then come into his room. In two minutes, he’d ask questions that made you realise you hadn’t thought about some aspects... And you come out of there frustrated and say, ‘How the hell did he do that?’”

Focus on the specifics feeds Tata’s feel for the big picture, as he spelt out at a fireside chat with Kola in Bangalore. “There needs to be financing capability to provide funds to promising companies,” he said. And then, compassion for failures. “The fall of an enterprise has to be a lesson learnt rather than something that demolishes the reputation of the individual running it.”

Though Tata never had to bootstrap a business, there is tremendous regard for his risk-taking and understanding of failure. His first independent assignment in the Tata Group was to head consumer-electronics company National Radio and Electronics (Nelco), from 1971. It was a loss-making unit, which he managed to turn around briefly. But the stint was excruciating, as Tata encountered external issues like the Emergency and labour disputes. In the TV era, Nelco produced brands like Blue Diamond, but he had to take hard calls to exit the market as Japanese and South Korean manufacturers were on the ascendancy in the ’80s.

Tata’s attitude to enterprise has always had a touch of New Economy derring-do. “You can be attached to a particular business because you are emotional about it, or driven by the need to make it successful. You have to stay with it to overcome initial difficulties, or let it go, cut your losses, and learn your lessons from it,” he said. Goel of Urban Ladder says Tata’s experience across industries allows him to be somewhat doctrinaire, “but he chooses not to”, and that’s something young entrepreneurs appreciate.

Tata’s interest in the nouvelle vague is an extension of a larger family tradition, dating back a century, of giving a leg-up to forward-looking enterprises. The founder of the Tata empire, Jamsetji Tata, started a cotton production and shipment company, diversified into steel, and then hospitality. He also wanted to generate hydroelectric power from the waterfalls at Lonavala, Maharashtra, to replace coal.

Jamsetji didn’t live to see his steel or hydroelectric ventures come to fruition. But when Tata Steel and Tata Power came to life in 1907 and 1919, it was primarily because Jamsetji’s son Dorabji Tata had worked closely with his father in managing Tata companies since 1884. He imbibed the values, aspirations, and ideals of Jamsetji. The tradition was carried on by successive heads of the empire, including JRD.

JRD’s own legacy was civil aviation (Air India), in which the Tatas had 20% stake before the government acquired it in the Indira Gandhi years, a cargo service between Mumbai and Karachi, and Tata Chemicals (1939). Before his death in 1993, he had mentored and groomed RNT for nearly six years to be chairman of the group.

Mentoring is something of a Ratan Tata speciality, as Mukund Govind Rajan, member of the Tata Sons Group Executive Council, will tell you. Rajan served as executive assistant to Tata when he was chairman. “The way he treated everybody just made you care so much about your job, even when he was not around. Ultimately the buck stopped with him and his office—he never let us forget that.”

Tata reminded the group’s management protégés that there are many stakeholders out there for whom they are the last resort. “[For] anyone who worked with him, that got [driven home] very quickly: Don’t disappoint, don’t let down people, whether it is customers or shareholders. In many companies, these are dismissed as nuisance. He would always say put yourselves in the other person’s shoes, and then see whether the way you are treating them makes sense. He elevates everything around you,” says Govind Rajan.

A lot of that has to do with the Tata culture and its federal structure, says Bhaskar Bhat, managing director of Titan. “Leave companies to do what they want to do, but expect them to excel at what they do. Mr. Tata’s articulated goal to most Tata enterprises was: Be either No. 1 or No. 2 in the businesses that you choose to be in,” he recalls. Operationally, Tata preferred reserving his opinion because management teams would otherwise feel bound to toe the chairman’s line. “He is very conscious of that, and so used his power and position very judiciously,” says another associate, who asked not to be named.

For the chosen few, stars all in a country that is quick to idolise, wearing success lightly is the real lesson. Says Kar: “Almost everyone looks up to him for an understanding of leadership. How do we evolve from being founders to leaders? How does the company become larger than the founder?”

Kalaari, which has shaped the contours of Tata’s role as advisor to the likes of Kar, is yet to put in a place a formal structure for meetings. But the entrepreneurs are already thinking about how to make it all worth his time. Goel says the big pay-off will be if Urban Ladder’s performance can make Tata increase his investment in the idea of the company and what it stands for.

“I sense a great remorse that I am in my seventies and not in my forties, because young people are coming into their own and having an opportunity to express themselves, innovate, and establish enterprises,” Tata told an interviewer in December, while unveiling the XPrize in India. XPrize India incentivises competition, notably in water, energy, waste management, and food and nutrition. Tata has been on the XPrize board of trustees since 2009, a list that features SpaceX founder Elon Musk, Google co-founder Larry Page, and futurist Ray Kurzweil.

“There is a part of him that enjoys the spirit of a contest,” says Zenia Tata, who heads global development and international expansion at XPrize. At an XPrize conference in Los Angeles last May, the 100 attendees were discussing the next breakthroughs. They divided into teams to brainstorm what new prizes ought to be instituted. Tata formed an India team and designed an XPrize for affordable housing. He was up there, in front of these groups, to pitch the idea. “His team finished second, but he liked the competitive spirit, the model of large-scale innovation,” says Zenia.

At the Bangalore event, Tata was clear about why he supports young entrepreneurs. “[They] will make a difference to make the best companies win.” To which Kola later told me: “He is doing it out of pure joy in what he thinks and believes in, to support Indian entrepreneurs.”

Broadly, Tata empathises with young entrepreneurs. “[The entrepreneur] risks his personal net worth and several years of his life to making something happen,” says Kola. It is not driven by the greed of making a fortune but leaving a mark on the community, customer base, and marketplace.”

Kar, who benefitted from this spirit of benefaction at Noamundi, thinks it is the greatest value Tata brings to the winner-takes-all digital age. She remembers her missionary-school education on a J.R.D. Tata scholarship. “The vision they had to build a township, to ensure that it had good schools ... it made sure I never felt that I came from a very small place. That speaks of a leader who is not building a company for today, but thinking of the lives he would influence in the here and now as well as in the future.” Now to build a valuation algorithm sophisticated enough to price that.