The invisible entrepreneurs

ADVERTISEMENT

Vani Kola is one of three managing directors at Bangalore’s $350 million (Rs 2,141 crore) venture capital (VC) fund Kalaari Capital. That in itself is not cause for much comment; there are several women in the financial services space, with many ranked among the 50 most powerful businesswomen in India. So Kola is not necessarily a stand-out; her story could be the story of everywoman. Except it isn’t. (Kola has entered our list this year at No. 48.)

Back in 1997, then in San Jose, California, Kola, aged 33, founded RightWorks to help large companies organise their supply and procurement on an intranet platform. Silicon Valley investors made time for RightWorks because when consumer Internet companies like Amazon and Yahoo were the rage, her idea was innately different and sharply defined. In six months, Kola’s team raised $1.5 million in funding (including angel investment from Suhas Patil, renowned for founding semiconductor company Cirrus Logic).

RightWorks got its customers in place, and was growing steadily. And then, in July 1997, Kola announced that she was pregnant with her second child. “I was very nervous that my board and investors might get upset,” she recalls. But they were very supportive. Patil, she says, told her there was no reason to be apologetic or nervous.

The larger venture community, however, didn’t see it the same way when she tried raising more capital six months later. “I don’t see how we can invest in a pregnant woman,” said one potential investor bluntly. Kola was taken aback, but philosophical. “One can be activist about it, say it is unfair, and so on. Or, as an entrepreneur, you can be pragmatic and not be offended.” She chose door two, and instead of seeking more capital, began consolidating RightWorks’ operations with existing resources.

Kola explains why she chose the more passive-seeming option, saying that the investors’ concerns were valid. If an investor is writing out a cheque for $5 million or $10 million, she notes, it is natural to be worried about a founder who will be taking months of maternity leave.

Any technology entrepreneur—man or woman—who wants to cut it knows that a high-velocity startup will be your only life for five to eight years, she says. “It is a single-minded effort with very low probability of success. You put your life on hold. This is where men have natural support systems [wives] that don’t exist for women.”

Unfazed by the experience of being refused investment, Kola even set up a second company, Certus Software, in California, before returning to India. (Incidentally, three months after her second daughter was born, Sequoia invested in RightWorks. All of them exited in 2000, with RightWorks valued at $1.2 billion.)

Back home, she made the shift that serial entrepreneurs seem to inevitably make—into funding. In partnership with Vinod Dham (ex-Intel, where he was known as the ‘Father of Pentium’), she set up IndoUS Venture Partners to provide early and mid-stage funding to new or growing businesses. In 2012, when Dham moved on to set up his own venture fund, IndoUS became Kalaari Capital, a fund to make early investments in tech startups.

Kalaari’s investment in at least three companies (Zivame, Embibe, and The Label Corp) started by women makes a statement, especially in the context of what Patil once told Kola. He had said that all else being equal, if he had to choose between investing in a company started by a man and one by a woman, he’d invest in the latter, because he wanted to create role models for women, besides funding a business he believed in.

Kola’s Valley story could well be the story of any woman wanting to enter the technology space as an entrepreneur. It’s not that promising business ideas come easier to men than to women; it’s just that the environment, particularly in technology, is, and has been, implicitly biased. It’s a global problem; the huge under-representation of women in technology startups is the butt of an insider Silicon Valley joke called the ‘Dave rule’, that there are as many women in a team as men named Dave.

But it’s not so funny when an established company like Google reveals that globally 70% of its workforce is male. Google can pump in millions of dollars to encourage women to enter technology (as, indeed, it did). But the problems of a woman trying to start a company are vastly different. As Kola found, even personal choices about starting a family are boardroom issues.

India has barely 100 women who have built companies in a technology industry that employs 1.3 million women. This, when 800 tech startups are formed every year in the country. That’s not just a gender gap. It’s a yawning chasm. And one of the chief causes for this is a skewed system that favours male entrepreneurs over females right at the early funding stage.

It’s up to the venture community to acknowledge and address the imbalance; when asked outright about how many women-founded startups they had funded, at least two global VCs in Bangalore were stumped.

In India, the venture industry has, since 2005, deployed around $8 billion of capital, mostly in tech startups. Companies with male co-founders, like MakeMyTrip, Flipkart, Snapdeal, and InMobi, have raised between $200 million and $2 billion. There are no authoritative sources to show how much of the $8 billion went to women founders, but a back-of-the-envelope calculation shows that it cannot have been anything more than 2% and closer to 1%. According to a Bangalore-based VC, who asked not to be named, perhaps only one woman in India has been part of a tech venture to have raised more than $30 million in multiple rounds. That’s Meena Ganesh, who co-founded education portal TutorVista in 2005 with her husband.

It’s true that industry at large, particularly services sectors such as banking and finance, health care, and information technology, has managed to bring more women into the organised workforce. Although India Inc. has a long way to go in providing gender-neutral workplaces, efforts are being made in that direction. The IT industry, in particular, has made some progress from being the old boys’ club it was in the ’80s. Companies like Infosys and HCL started out in a far more orthodox social milieu. It was also an age when jobs were hard to come by, and the generally unstated assumption was that employment in tech areas was reserved for men. Today, the IT industry employs more than 1 million women, and there’s a 17% to 30% representation of women in large companies.

But when it comes to women from this industry dropping out of their day jobs to start up, the pitch is heavily queered. With economic liberalisation, even as more women became part of the workforce, many became a crucial source of financial security when their husbands started up. (For instance, when serial entrepreneur Krishnan Ganesh left HCL to start IT&T, wife Meena stayed on at Microsoft, and later at Tesco Hindustan Service Centre when he started up analytics firm Marketics.)

There are certain businesses where being a woman helps. Richa Kar, 33, founded online lingerie store Zivame.com in July 2011. Because she understood the potential of the business, and the opportunity, better than any man could, she was able to pitch the idea well. The problem Zivame identified was how the category was supply-driven. Due to a wide range of bra and lingerie sizes, not all sizes were stocked in shops. Kar uses the portal to provide a broader range to customers, and then gives data-based instructions to manufacturers. Zivame has expanded the range to include posture-correcting bras, mastectomy, and post-surgery bras. Kar has raised $16 million in two rounds over the past two years.

(bottom) Neetu Bhatia, co-founder, Kyazoonga

January 2026

Netflix, which has been in India for a decade, has successfully struck a balance between high-class premium content and pricing that attracts a range of customers. Find out how the U.S. streaming giant evolved in India, plus an exclusive interview with CEO Ted Sarandos. Also read about the Best Investments for 2026, and how rising growth and easing inflation will come in handy for finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman as she prepares Budget 2026.

But the going is not easy for those who want to take the plunge. Outdated cultural biases come into play, and the perceived expectation of meeting domestic responsibilities hinder many from taking risks, even in cases where women can potentially afford to.

Sharon Vosmek, CEO of Astia, a network based in San Francisco that identifies women-led ventures poised for growth, explains why, globally, women entrepreneurs are often overlooked by VCs. It’s a variation of the old boy’s club, where early-stage investments are discussed at networking events (which see few women) or over dinner meetings that women (particularly those with families) are often unable to make. Further, Vosmek says, “95% of VC partners today are men”, who seek to invest in “people like them”.

What can break the club is more women entering the tech space, both as entrepreneurs and as investors. This could redirect the flow of smart money and make funding more equitable. Consider, for instance, ticketing portals Kyazoonga and Bookmyshow. Both sell event and movie tickets online. Kyazoonga was co-founded by Neetu Bhatia, while Bookmyshow was founded by Ashish Hemrajani, Parikshit Dar, and Rajesh Balpande. With a gender-neutral investing community, both startups should have received similar funding. In reality, Kyazoonga got $5 million, while Bookmyshow has raised more than $40 million since 2012. Admittedly, this is where the whole gender debate gets complicated. Given the biases, it’s easy to blame this discrepancy on the fact that Bhatia is a woman and the Bookmyshow founders are men, although that could be doing the founders of both companies, as well as the investors, a disservice.

Even a couple of decades ago, the blame could have been laid at the doors of an inequitable educational system, where girls were actively discouraged from courses in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). Women who managed to get into engineering college, even in the ’80s and early ’90s, were routinely told by teachers that they were depriving a man of a seat. Or they were disparagingly called ‘modern’, implying they were better off in their traditional roles as daughters, wives, and mothers.

However, with government initiatives to improve the gender ratio in STEM courses and with colleges realising that it was self-defeating to close their doors to women, the situation has improved. According to data from the Ministry of Human Resource Development, 1.47 lakh women enrolled for undergraduate-level computer science courses in 2011—that’s 42% of all students enrolled in those courses that year.

There are still far fewer women than men in the premier engineering colleges—the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) and Birla Institute of Technology and Science (BITS). A dipstick survey shows that VCs are more inclined to back IIT and BITS alumni, especially in big-ticket tech deals. In the IITs, women account for roughly 10% of the students enrolled. BITS, meanwhile, has taken serious steps to improve the gender ratio, and in 2003, women accounted for 42% of the student population, up from 24% in 1996. However, new admission norms have played havoc with this, and the proportion of women fell to 13% last year. Raghurama G., director of BITS Pilani, says the authorities are taking steps to improve this.

“Risk-taking and being adventurous are often seen as male traits. If the ratio [of female students to male students] is low, female students will find that their voices aren’t heard,” says Raghurama. “A healthy ratio will help them be more assertive. It will increase their confidence and allow them to be bolder.” He adds that female students bring a different perspective to decision-making. “Without being judgmental on who has greater skills, it is amply clear that gender diversity in groups brings greater value to the quality of decision-making and the learning itself.”

Fixing the feeder system—STEM education—is not enough, as a recent report by Catalyst, a research non-profit for advancement of women in business, notes. Only 18% of women (compared to 24% of men) it polled opt for business roles in a tech-intensive industry for their first job after an MBA. And 53% of women left tech-intensive industries after the first post-MBA job, compared to 31% of men. “STEM companies face a serious talent drain as women take their skills elsewhere,” says Deborah Gillis, CEO of Catalyst, referring to the findings.

In his book The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution, Walter Isaacson talks of how deeply sexist the industry was even in the 1940s. He tells the story of Jean Jennings, one of the earliest American computer programmers, who was part of an all-woman team programming ENIAC, the world’s first general-purpose electronic computer. When ENIAC was unveiled to the press and public to much excitement, the men who built the computer were feted; the women programmers completely forgotten. Isaacson quotes Jennings: “The boys with their toys thought that assembling the hardware was the most important task, and thus a man’s job.”

Little has changed since. One of the big reasons for women to leave tech-related fields is that it is defended by some as one of the last bastions of men. Recent controversies, including what’s being called Gamergate, also expose the misogyny in the industry, forcing women to leave.

It’s a fraught issue, and without adequate support systems, women will continue to leave the industry, as Gillis points out. Sheryl Sandberg, COO of Facebook, has one answer in her bestseller Lean In. Women in power, who are willing to help other women, will give the network of women a boost. “The first wave of women who ascended to leadership positions were few and far between, and to survive, many focussed more on fitting in than helping others. The current wave is increasingly willing to speak up. The more women attain positions of power, the less pressure there will be to conform and the more they will do for other women.”

In India there haven’t been nearly enough networks of women, for women. There are a few, of course, notably the Ficci Ladies Organisation (FLO), a division of the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry. FLO works to promote women’s participation in management and enterprise. Indian Business & Professional Women (IBPW), a similar, albeit smaller body, functions as a support network.

Others focus on specific aspects of entrepreneurship. Shaleen Raizada, managing director and CEO of Sanshadow, has built a network of over 100 women Ph.D.s since 2004. Sanshadow is an intellectual property rights consultancy, which helps identify patentable technologies and advises clients on how best to modify new technologies so that they become patentable and commercially viable in India. Raizada says the Indian Angel Network helped her scale up in the country and beyond, emphasising that the network effect is crucial to the development of new ideas.

In February this year, the N.S. Raghavan Centre for Entrepreneurial Learning at Indian Institute of Management Bangalore launched an ‘Alumnae and Women Entrepreneurs’ programme. Similarly, WEConnect International helps women-owned businesses succeed in global value chains by mentoring and endorsing women’s business enterprises based outside of the U.S. that are at least 51% owned, managed, and controlled by at least one woman. There’s also The Indus Entrepreneurs’ Stree Shakti movement, which aims to connect and enable enterprising women from different socio-economic strata through a series of on-ground initiatives.

It’s a beginning, sure, but what’s really needed to help women enter the startup space is for the VC community to be aware of their potential. A start has been made globally, with networks like Aspect Ventures and Astia. Theresia Gouw and Jennifer Fonstad left their jobs, Gouw at Accel Partners and Fonstad at Draper Fisher Jurvetson, to found Aspect Ventures. They, along with Monica Dodi, co-founder and managing director of the Women’s Venture Capital Fund, are among the few women VCs in the industry. “If we think there should be more diversity in venture capital, let’s change what investors look like,” Gouw wrote in a Wall Street Journal blog post.

Previously known as the Women’s Technology Cluster, Astia was founded in 1999 by Catherine Muther, formerly a senior marketing officer at Cisco. It sought to expand women’s access to capital and startup opportunities after taking into account the underrepresentation there—only 2% of venture capital in the U.S. went to CEOs and founders who are women.

“In the U.S., women are half of the Ph.D.s, half of the MDs, and half of the MBAs. So we have this abundant talent pool. It’s not as if these women need further training and mentoring. What needs to be redesigned is the set of networks that support women through their entrepreneurial journey,” says Vosmek. The Astia community, for instance, backs the most promising, investment-ready companies identified by a global network of over 5,000 investors, industry experts, and serial entrepreneurs.

In India, Nasscom is trying to be an Astia. “In the technical and product aspects of startups, we see a lot of scope for founders, regardless of gender,” says Rajat Tandon, senior director of Nasscom’s 10,000 Start-ups programme. Tandon says women

have built up a significant pool of technical expertise.

In the first phase of its programme to incubate entrepreneurial ideas, Nasscom received 7,000 applications, of which 540 had at least one woman co-founder. Tandon says many women entrepreneurs focussed on service-oriented ideas like e-commerce, fashion, parenting, and wedding planning. “We feel the [scope for] funding is low in such ideas,” he argues, adding that the number of women-run startups can explode, if they build more product companies. From the programme’s third phase, the participating startups will have to state the gender of their founders. Nasscom expects the 8% women representation in the programme to double at peak.

To this end, Nasscom has organised 20-odd senior leaders to mentor college and schoolgirls on how to develop mobile applications. There was a women-only digithon as well for two days in Bangalore, where women got help and experience in validating ideas, building business plans, marketing, and design. About 150 women, including college-goers and working women, participated. (Incidentally, Neha Singh, co-founder of Tracxn, which helps private equity and venture funds track and find new businesses across sectors, says Bangalore has the largest number of women-run businesses.)

The good news is that in a sample set of investment-worthy startups in India’s Internet sector, Tracxn found promising signs between 2010 and 2014. Seven out of 58 ventures (12%) founded in 2010 had at least one woman entrepreneur. And 23 out of 157 ventures (14.7%) founded in 2014 have at least one female entrepreneur.

Then there are unsung success stories like Madhumita Halder’s MadRat Games, which builds board games for offline and online platforms in Indian languages, or Kavita Iyer’s campus and education network Minglebox. There’s also Aditi Avasthi, 32, who founded Indiavidual Learning in Mumbai in Sept. 2012. The data sciences platform raised $4 million in its first round this year. Indiavidual’s online test platform Embibe helps students identify blind spots in exams for the best engineering seats in the country. Students log in to Embibe and solve practice tests, which are assessed by Indiavidual to recommend areas of improvement to the students, their parents, and teachers.

In May, LimeRoad, a social commerce website co-founded by Suchi Mukherjee, got a second round of capital ($15 million) led by Tiger Global. (Two years ago, venture funds Matrix Partners and Lightspeed had invested $5 million in it.) LimeRoad is one of the few startups run by a woman founder to have received a second round of funding.

Tracxn’s Singh says that for more women to consider starting businesses in the tech space, it is important that the system “facilitates achievements and risk-taking abilities”, and also, over time, recognise and reward the winners.

The problem is that “women’s” ventures don’t have too much traction with the investing community (possibly because there are so few women in the VC space). So, for instance, an idea such as Menstrupedia, the brainchild of Aditi Gupta, may never see the light of day. (Tracxn has identified Menstrupedia, a web-based health guide in comic form for young girls to understand menstruation, as an investable idea, though there have been no takers yet.) Without ventures such as this, there will be far less diversity in the startup space. As it is, Nasscom and Tracxn, in their respective capacities, find that women entrepreneurs tend to stick to certain “women’s” fields such as parenting, food and cooking, and fashion. The other problem with not encouraging different ideas is that there will be fewer failures to learn from.

Explaining why women founders are a casualty in the startup ecosystem, Astia’s Vosmek asks me a question. “Do you know who Diane Greene is?” I don’t. Most people struggle to place Greene, the co-founder of VMWare and board member of Google, despite her having built a pioneering business at the forefront of cloud and virtualisation software and services.

Could that be because the business itself is not one that’s in the public eye? It’s not so much that businesses are low-key, says Vosmek. It has to do with the leadership style of the founder or promoter. “There is an entire leadership style that is undervalued in venture-backed startups,” she says.

A lot of that has to do with gender. “There is a very specific stereotype of entrepreneurs that gets reinforced over and over again. At one level, the Steve Jobs story is like the Mark Zuckerberg story is like the Marc Andreessen story is a bit like the Larry [Page]-Sergey [Brin] story. [This breeds] an almost monolithic style.”

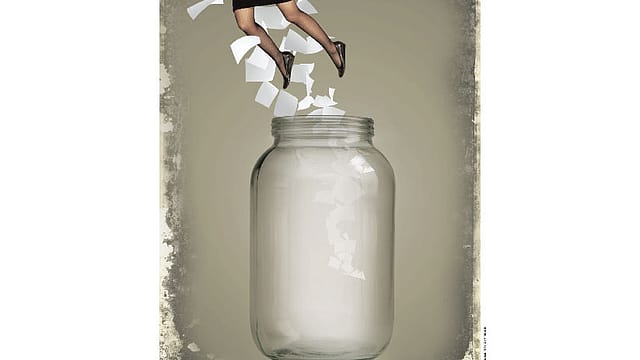

Gillis of Catalyst says almost the same thing: “Nearly all [iconography] of leadership and the attributes required to be successful in business tend to be stereotypically male.” Vosmek says women come to the table with very different experiences and perspectives. “That difference is invaluable to leadership.”

Difference in leadership styles needs to be celebrated for another reason: to make successful women entrepreneurs visible role models for those who come after. Today, there’s a startling dearth of women who have the iconic status of, say, an N.R. Narayana Murthy. But with more money flowing in to fill an obvious gap, and more women setting up shop, perhaps the image of everywoman will begin to change.