Create fiscal space for UBI: Abhijit Banerjee

ADVERTISEMENT

Universal Basic Income (UBI) has outgrown scholarly debates and is being actively discussed by policymakers worldwide; it was even mentioned in India’s Economic Survey last year. At a press conference after the release of this year's survey, chief economic advisor Arvind Subramanian went further to say that at least one or two states will implement UBI over the next two years.

To understand the benefits, challenges, and feasibility of UBI in India, Fortune India spoke to Abhijit Banerjee, professor, Department of Economics, MIT and co-founder of the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab. Edited excerpts from the interview:

Is UBI a good idea, and will it work in a country like India?

As an idea, it is a good one. But it is an untested good idea. Right now, many, including me, are involved in various evaluations of UBI. As an idea it is a very good one because it comes through a bunch of potential inefficiencies that other welfare systems have. That’s why people like it. Is it actually going to work on the ground? We don’t know.

January 2026

Netflix, which has been in India for a decade, has successfully struck a balance between high-class premium content and pricing that attracts a range of customers. Find out how the U.S. streaming giant evolved in India, plus an exclusive interview with CEO Ted Sarandos. Also read about the Best Investments for 2026, and how rising growth and easing inflation will come in handy for finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman as she prepares Budget 2026.

And about a country like India…in some ways, the whole point of this is for countries like India. Because we are not very good at designing welfare schemes that are well implemented and well targeted. So the advantage of making it universal, without much targeting, and giving up on the idea that it needs to be targeted. [For instance], think of NREGA, which is an extremely elaborated well-targeted scheme; but those have their own costs, many people get excluded.

I think the big plus of something like UBI is that it is straightforward. As a concept, there doesn’t have to be ten steps in it. You can just send everybody a cheque, every person of a certain age and every woman a cheque, and you don’t have to worry about if you got the targeting right, or like in the case of PDS, to make sure if the food shows up at their doors. There are a million things that go into the design of most other programmes. [In contrast] this one [UBI] has an advantage.

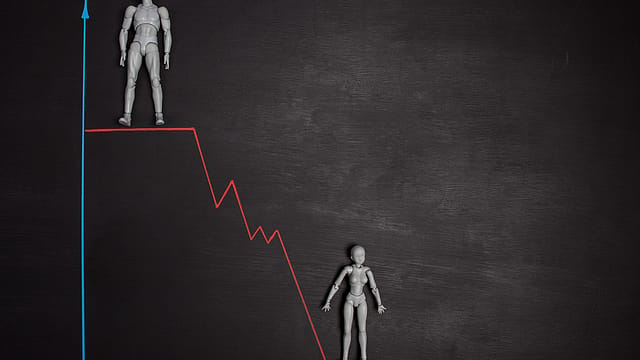

Do you believe that UBI can be effective in addressing inequality?

Surely, the extent to which a country as fiscally strapped as India can afford it will depend very much on what we can do. So, if we are going to give people Rs 20 a month, it is not going to address inequality. It has to be relatively generous to do that. And for that we need to remove all the very difficult–to-remove middle class subsidies. Like the subsidy to Air India. It is just a complete unashamed waste of money. We have been doing it year after year. There was a parliamentary committee which said: ‘well we need to look at it for another ten years’. If we continue to give subsidies to the middle classes, we won't have money to reduce inequality.

First, we have to create fiscal space for it. And the way to create fiscal space is by getting rid of a bunch of extremely inefficient subsidies that we continue to have. So far, there has been some progress—we have reduced LPG subsidies, and diesel and petrol subsidies. This is a good thing, we have to hold the line on that. I am a bit worried that once the prices start going up, the government will lose its nerve on that. But it is really important to hold the line on that.

These are all things that need to be somehow be taken on as part of an agenda. Then we will have the fiscal space to actually redistribute to the poor rather than the middle classes. Like a lot of the fertilizer subsidy goes to the high end of the farming community, therefore that is not doing a huge amount to reduce inequality.

The determination of how much this particular income should be is very important. How should UBI be determined to make it fair?

There is no universal principle of determination. The key is to create fiscal space for UBI. A lot of people who have written about it are basically arguing that we have to first decide which subsidies can be politically taken off, and then we can arrive at a figure. I could say let it be Rs 2,000 a month, but that would be irrelevant if we can’t afford it. There is no point creating a budgetary crisis. We don't really have that degree of freedom right now—there is no money. I don’t think there is budgetary space for doing something else right now. There’s a need for some hard decisions on where the money is going to come from.

Will it address gender inequality?

Some people have pushed the idea of just targeting it only to women. Then, of course, it will address gender inequality to some extent, particularly the extremely egregious inequality that older widows face. If I had to start with one group, I would start with older single women.

In contrast to India, how will implementation of UBI be different in a developed country?

The amount available is an obvious difference. Another is the advanced state of debate. For example in Europe, there are a lot of programmes that are targeted to the unemployed or the underemployed. Thus, there is at least an argument that these generate disincentives. Therefore, there is the argument that UBI would remove these disincentives. I am going to give you a flat amount of money, if you go make more out of it, that's good. If you don’t, you don't. We don’t care. That means you have no disincentive. There is no phase out.

UBI is universal and therefore kind of unconditional on whatever your outcome is. That point is very important in a context where the welfare system is well-developed. In a country like India this is not a concern because we don't really have the same kind of a welfare system.

An argument against UBI is that free money has no reciprocity. As an economist, does that make sense to you?

I think that argument makes no sense. I never understood it, I don’t mean to understand it. We don’t want to live in a society where people are starving to death, and to create work, make people do things that are not particularly useful so that we can make sure there is some justification for giving money to them. It looks like cutting off your nose to spite your face. We all care about social objectives. We don’t want people to be starving, we want social peace, we want people to be not desperate. We want a society where extreme poverty doesn't exist. We want people to feel that they are living in a civilised society. We want people to feel that there is security because people are not desperate. We feel safer in a society where people are not desperate for money.

There is a social reason to redistribute. I have done some research on these subjects and my impression is that when people have opportunities, they feel more secure about their lives—they actually work harder. If you give people Rs 2,000 to Rs 3,000, I don’t think they will retire on that. If anything, they will feel more empowered to go out and do more things.