Those inflation blues again

ADVERTISEMENT

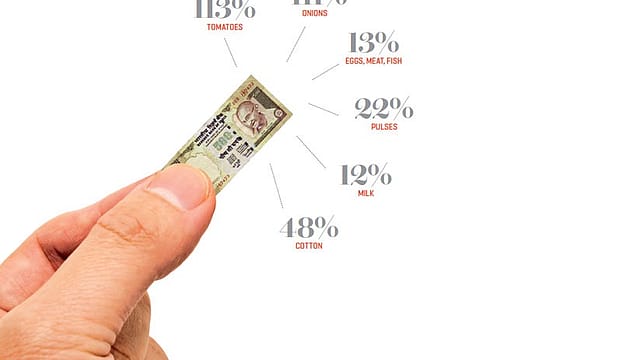

AROUND THE END OF 2010, onions were going for something like Rs 80 to Rs 90 a kilo, a rise of 111.58% in the last one year. The last time onion prices rose so dramatically was in 1980, when the ruling Janata party-led coalition was routed during the elections, largely because it couldn’t keep prices from zooming up to Rs 5 a kg. This year, the story is not just about onions: The vegetable price index has shot up by 67% over the past year.

Today, the government is busy making soothing noises to convince people that the recent steep rise in food prices is temporary. But not everyone is buying the official estimates, which say that the general rate of inflation could come down to 7% by the end of March. Besides, that number is still higher than the Reserve Bank of India’s comfort level of 5.5%, and there’s no guarantee that prices will fall even in April or May with the arrival of the new harvest.

Persistent high inflation can negate the impact of strong demand, which shores up sales growth in an expanding economy like India. It affects purchasing decisions, as people wait for prices to fall. Supply side shocks can also lead to higher imports of scarce commodities, which can lead to a widening balance of trade. Since high inflation impacts the poor more than the rich, it has serious political implications.

This time around, unlike in the late 1970s, rising prices are not expected to lead to riots. Damodar Mall, director of food strategy at Future Group, which owns the Big Bazaar retail chain, says the reaction to rising food prices hasn’t been as strong as it would have been a few years ago, because middle-class families have a cushion provided by higher incomes. Shoppers, particularly from the middle class, have tried to adjust their consumption to absorb the increase in prices rather than protest on the streets as they might have done a few years ago. Mall points out that people bought less onions to beat the price rise.

There were no immediate causes for the steep escalation in the prices of food items. In fact, vegetable prices usually dip towards early December because of higher output.

The excessive rains in November and December 2010 could have hurt production, and hence the price of onions, but even that doesn’t explain the higher prices of other food items. There’s been no natural disaster as in 2009, when the worst drought in three decades resulted in supply disruptions and hence a steep increase in the price of several food items.

“Quite clearly, the current inflation has been driven by primary articles. It’s visible in the case of cereals and pulses, and has been very sharp in the case of perishables,” says Shubhada Rao, executive vice president and chief economist, Yes Bank. Sunil Sinha, senior economist at credit rating agency Crisil, adds that this could be because of “the supply shock in agricultural commodities”.

While the reason for the current rise in prices rate may be agricultural, the impact of inflation is widespread. For one thing, high inflation curbs consumption of non-durables. It also translates into rising interest rates. So, industries in general, and interest rate-sensitive segments in particular, such as banking and financial services, auto, white goods, and real estate get hit directly. “Then, there’s also the wage-price spiral (increase in wages) across all industries, with a lag effect,” adds Sinha.

Some domestic prices—auto and consumer durables—have already risen because of higher input prices. Prices in other industries are expected to follow as margin pressures build up. With the price of palm oil—a key ingredient of soap—already up by 45% from last year, soap manufacturers such as Hindustan Unilever and Godrej Consumer Products have been forced to raise the prices of their goods.

Not everyone is perturbed by the current situation. Says Venugopal Dhoot, chairman, Videocon Group, a Rs 10,572 crore consumer goods conglomerate with interests in oil and gas and telecom: “Nobody should be concerned, since both growth rates and incomes are moving upwards. Growth and inflation will necessarily need to travel with each other at a time like this.”

Andrew Holland, CEO, equities, Ambit Capital, explains how high inflation can become a country’s Achilles heel. “A scenario of high inflation rates coupled with high interest rates is never a good situation to be in. Rising interest rates have a bearing on growth decisions like investments and capital expansions.”

The BSE Sensex—an indicator of the country’s prosperity—has already fallen 8.9% below its December peak of 20509 points. It was down to 18684 on January 28, three days after the RBI hiked its short-term lending rate (repo rate) by 25 basis points, from 6.25% to 6.5%. “That’s when the stock market has already buffered itself for a 50 basis point hike in interest rates,” says Holland.

Foreign investors have reduced their weights on Indian investments, and capital investments have turned into a trickle. “With high prices threatening to dent consumption, foreign investors believe that India’s growth story may be petering out,” explains a Mumbai-based investment banker. After all, consumption constitutes 66% of the country’s GDP growth, according to a recent report by Enam Securities.

While economic growth is starting to rebound in the U.S. and parts of the European Union after two and a half years of the meltdown, India seems to be losing steam. Some say growth doesn’t look very solid, especially in 2011-12. Nilesh Shah, managing director and CFO, Envision Capital, puts the issue in perspective. “Today, growth is not up to expectations, and there is pressure on margins. Besides, valuations are not necessarily that attractive. So the fear is that foreign investors may leave Indian shores for their own safer domestic markets,” he says.

India has managed to keep its current account deficit at a manageable 3.7% of the GDP, despite the widening trade deficit. However, if the foreign flow were to reduce dramatically, it could result in a liquidity crunch. A sudden reversal can be highly disruptive, because it would hurt private consumption, investment, and government expenditure.

Other issues related to persistent high inflation have started surfacing. High inflation rates mean that people are no longer putting their money into savings accounts. If the inflation rate is 8.3% (as on January 8) and the savings rate is 3.5%, it translates to a 5% negative real rate of return. The action, therefore, has shifted to gold and real estate—popularly seen as inflation hedges. This has raised fears of asset bubbles.

Liaquat Ahamed, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning book, Lords of Finance, raises questions about the fundamental soundness of both gold and real estate. “Prices in some parts of New Delhi are higher than those in New York. I don’t know in what universe that makes sense. Anything that has gone up as much as gold has is not a good investment now,” he says.

A declining loan-to-deposit ratio means that banks could face a liquidity crunch and might be forced to borrow at higher rates of interest. For instance, while bank deposits increased by 16.5% in the two weeks ended Dec. 31, 2010, from a year earlier, deposits were still lower than the 24.4% rise in lending, according to RBI data. This means banks had to borrow huge amounts from the RBI to take care of the lending.

But the real danger to the Indian economy comes from the fact that food inflation has come at a time when global commodity prices too are on the rise. In the past year, iron ore prices in the country have gone up by 41%, copper ore by 57%, and bauxite by 33%. Prices of other commodities too could have shot up, but for the government’s policy of not passing on the increase in prices to consumers. Internationally, however, higher prices of raw materials—especially coal and iron ore—are making steel more expensive. Steel makers, including AK Steel and Nucor in the U.S., China’s Baosteel, and South Korea’s Posco, have been steadily raising prices in recent months.

“The problem of inflation is not entirely restricted to India. It has become a problem for most emerging nations because global commodity prices have been on the ascent for a while,’’ says M.V.S. Seshagiri Rao, joint managing director, JSW Steel.

TILL NOW, INFLATION HAS BEEN SEASONAL or cyclical in nature, so prices would automatically drop once fresh arrivals entered the market. But that’s not happening now, and there’s been double-digit food inflation for the past two and a half years, even when the general inflation rate, reflected in the wholesale price index, was negative in June and July of 2010.

The problem with today’s inflation is one of supply, which can only be fixed by addressing food production and distribution. “The need is for a long-term plan that will enhance farm productivity through radical land reforms, use of better quality seeds, right use of fertilisers and irrigation techniques, and also address the infrastructure deficit and market imperfections in the farm-to-fork supply chains,” says Crisil’s Sinha.

Nearly 30% to 40% of fruits and vegetables are lost in transit. To prevent wastage, the government will need to set up cold chains, warehousing facilities, proper transportation, easy credit to farmers, greater private sector participation in the agricultural sector, and the like, says Ashok Gulati, director in Asia, International Food Policy Research Institute. Further, facilitating the entry of the organised retail sector, which could reduce the number of intermediaries, will help bring down prices for consumers, while also allowing farmers to get their due. Such measures typically test the government’s ability to take on politically sensitive issues.

The problem is that these solutions are all for the long term. There’s no quick-fix solution for supply-side problems. The government can, of course, announce that it’s acting swiftly to control prices. But steps such as importing onions from Pakistan to cool prices, banning the export of edible oils, pulses, and non-basmati rice, and preventing futures trading in certain commodities, are short-term measures.

The question is, what role can the fiscal machinery play to help ease the situation. Ahamed, a former investment manager, says that central banks can’t cure the shortage of food because they don’t grow food. “All they can do is control the supply of credit, which will end up hurting growth,” he says. Last year, the RBI hiked interest rates half a dozen times in quick succession, but that failed to bring down prices.

The biggest challenge, as RBI governor D. Subbarao admitted in mid-January, is to “calibrate monetary policy, taking into account the demands of inflation management and the demand of supportive recovery”.

Indications are that the demand-supply mismatch is likely to get worse in the coming years. Demand for food rises every year—both quantitatively and qualitatively—and supply is failing to catch up. Production has either stagnated or actually declined in many parts of the country. According to a study by the Delhi-based PHD Chamber of Commerce, while the population has increased by 1.4% a year over the past 10 years, the growth rate in food grains has only been 1%. In other words, growth of per capita foodgrain production in the country has actually turned negative, and continues to decline.

PART OF THE EXPLANATION LIES in the India growth story—an average growth rate of 8.4% in the past five years—and the successful introduction of many poverty-alleviation programmes such as the Mahatma Gandhi National

Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme, and guaranteed higher minimum support price for farmers. These schemes have helped raise the income of many poor families, who can now afford two meals a day. In many cases, they can spend on not just cereals and pulses but also on protein-rich food such as mutton, chicken, and eggs.

“Today, many poor families have greater discretionary income, so they can buy food even at higher prices,” says Crisil’s Sinha. “Therefore, demand is not falling even though prices may be going up.” That could explain why, in May 2010, the year-on-year inflation in protein-based food items such as pulses, eggs, fish, and meat peaked at 34%, when overall food inflation was 21.4%.

In a supply-constrained economy like India, even a slight increase in demand can play havoc with prices. There’s also the problem of hoarders, who tend to push prices up even further. In response to the current crisis, the government has taken measures to catch and penalise hoarders. However, punitive action typically has a limited effect, since the problem is too widespread.

So in the short term, there isn’t a whole lot the government can do to stem rising inflation.