Chasing down the past

ADVERTISEMENT

Ancient India is attracting big money these days. Fuelled by a sense of lost history at a time when India dreams of yet another stab at superpower status, entrepreneurs are funding projects that translate, simplify, and highlight achievements of Indian history for a postmodern generation.

These enterprises are both philanthropic and commercial but the goal is the same—to help Indians understand their own civilisational values and skills. Rohan Murty’s $5.2 million (Rs 32.8 crore) Murty Classical Library series of books published by Harvard University Press, or NIIT founder Rajendra Pawar’s university courses under the Asian Lens Forum, or Mohandas Pai’s yet-untitled project—these are all businesses that come from a deep-seated sense that modern India has little sense of its historical importance.

Manjul Bhargava, professor of mathematics at Princeton and winner of one of the world’s biggest mathematics prizes, the Fields Medal (and recently awarded the Padma Shri), sensed this lack of interest in history at the 102nd Indian Science Congress earlier this year. While the congress had Nobel Prize-winners and senior academicians from across the world presenting papers and chairing sessions, the media, he later complained to his friend Rohan Murty, only covered a single paper. To explain: One of the sessions, ‘Ancient Sciences through Sanskrit’, included a presentation on ancient Indian aviation technology, where the presenters spoke of how Vedic Indians flew around in aeroplanes that could move sideways and back, as well as up, down, and forward. The other presentations at this session were about real science and achievements, but in the frenzy of poking holes in made-up science, they received almost no coverage. This is what Murty, Pawar, and Pai are hoping to rectify, at least in part.

Murty, son of infosys founder N.R. Narayana Murthy, and a Ph.D. in computer science from Harvard, has given $5.2 million to set up the Murty Classical Library series of English translations of classical Indian works published by Harvard University Press. “I firmly believe that if we do not know where we come from, we will never know where we are going,” says Murty, explaining the endowment.

January 2026

Netflix, which has been in India for a decade, has successfully struck a balance between high-class premium content and pricing that attracts a range of customers. Find out how the U.S. streaming giant evolved in India, plus an exclusive interview with CEO Ted Sarandos. Also read about the Best Investments for 2026, and how rising growth and easing inflation will come in handy for finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman as she prepares Budget 2026.

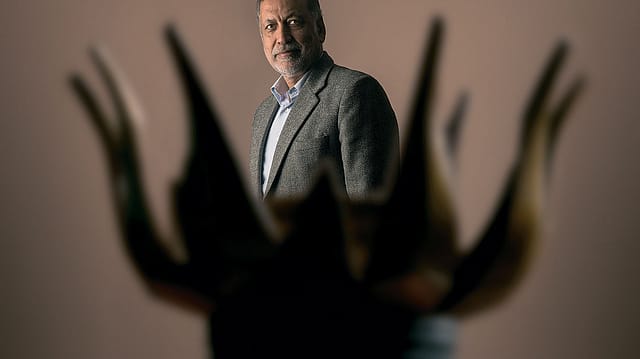

Mohandas Pai, chairman of Manipal Global Education and a former Infosys director, says private money in the West efficiently created “a world view that puts the West at the heart of history”. It’s time, he says, for Indian money to do the same. Pai adds that he was inspired by Murty’s effort to make ancient Indian classics accessible; his plan is to set up an institute to support research on ancient India. Pai won’t say how much he is spending on the yet-unnamed institute but says it will finance research projects such as those of the Indologist Rajiv Malhotra and make them accessible to the public. Malhotra, who has researched ancient Indian history, culture, and Hinduism for 30 years and written bestselling books on the subject, has argued that Western social sciences are often inadequate in understanding Indian philosophical constructs.

Then, there’s Rajendra Pawar’s NIIT, one of the country’s early technical training institutes, which offers courses in ancient history. “I remember a conversation with a friend from abroad who spoke to me about Delhi’s history, about how [the city has] seven histories. And I felt ashamed that I didn’t know enough about this. That got me thinking,” says Pawar, who set up NIIT University five years ago to teach management and technology. For a year now, it has also hosted the Asian Lens Forum, an initiative that the university launched in February 2014 to sensitise youth to their rich culture and history.

The idea, says Pawar, is to “create seamless classrooms so that anyone, anywhere, can access the treasures of Indian heritage. What we are trying to do in every discipline is to point out—emphatically—what Indian contributions were to global knowledge”. NIIT University has budgeted Rs 250 crore for this expansion over the next five years, of which more than Rs 5 crore will go towards events.

It is not new for entrepreneurs to finance the rediscovery of national heritage and culture; in the U.S., the Rockefeller family and Andrew Carnegie, who introduced the modern idea of institutional philanthropy, financed schools and institutes of research that built the edifice of American exceptionalism. The Rockefellers, for instance, funded much of the early pioneering research on race relations.

The projects that Murty, Pai, and Pawar are funding carry forward the work that 19th-century classicists of the Bengal Renaissance began. Back then, Nathaniel Halhed, William Jones, Henry Colebrooke, and Raja Rammohun Roy translated several ancient Indian works into English and other languages. Roy, from the aristocratic landed gentry, also bankrolled similar projects by other intellectuals. In fact, Sheldon Pollock, now founding editor of the Murty Classical Library of India, was looking for a modern equivalent of Roy when he was put in touch with Murty.

Pollock, a leading Indologist and Sanskrit scholar, had been editor of the Clay Sanskrit Library (which had brought out 56 volumes of Sanskrit literature translated into English), till American philanthropist John Clay withdrew funding. Pollock wanted to continue his job of bringing out good translations of ancient Indian literature. It was an idea Murty had been toying with since 2008, when he was a student at Harvard, and began studying Indian philosophy after decades of studying the Western systems. He began to talk about his interest with Parimal Patil, professor of religion and Indian philosophy, and the chair for South Asian Studies at Harvard. Taking Patil’s classes drove Murty to understand that “there was a market and a demand that we have been completely missing”.

A common friend put Murty in touch with Pollock, and the Murty Classical Library was born. Pollock told the young computer engineer that his area of operation could be widened—at almost the same cost. “Why only Sanskrit?” he asked Murty. “Why not all Indian classical languages?” Pollock talks about the venture as one of the “biggest projects of translation of classics ever done in the world”. Murty says he understood scale and impact talking to Pollock. “He took the idea to a whole different level,” says Murty. “In a venture like this, I realised scale was critical. We needed to think really big.” At the moment, the project is looking at bringing out at least 500 books—some five a year—translated from around 20 languages. The first set of books features languages such as Pali, Persian, old Telugu, and Punjabi, and include works such as the story of Manu, the first volume of the history of Akbar, and poems of the first Buddhist women.

“Because we were subjugated for so long, we forgot how to look at history our way,” says Pai. That’s a sentiment Pawar agrees with. “There is still a deep-seated inferiority complex among us,” he says. “We have to rediscover our identity.” Pai elaborates, saying that though some of the early British colonisers tried to understand Indian culture and even translated the Vedas and Upanishads into English, by the 18th century, the British began seeing themselves as a race whose customs needed to be imposed on the locals. The result, says Pai, is that by the time India gained independence in 1947, “we had learnt to be ashamed of ourselves”.

It’s not a question of denying the ills of the past like casteism, says Pai. But in the enthusiasm to cleanse the system of these ills, the baby tends to get thrown out with the bathwater. What does an Indian school student learn about the great philosophical treasures of India, asks Pai. Murty echoes this sentiment: “I had to do this project because otherwise, for all you know, the next generation would think that Indian history began in the 15th or 16th century.”

Pawar approaches this a little differently with the Asian Lens Forum, an ‘experimental classroom’ where speakers sit on a revolving stage with cameras on all sides and with a live and virtual audience of students. NIIT University’s curricula are being revamped to ensure that every course has new portions which talk about the achievements of India—from ancient mathematics to history, geography, and culture. These lessons will also be made available online to anyone around the world, not just to students but also to teachers in other colleges. Meeta Sengupta, a former J.P. Morgan investment banker-turned-educationist who ran the India Centre at the London Business School and is a Salzburg Global Seminar Fellow, will be teaching one of the courses. “The process of disseminating a sense of history in civic society is an important assertion, perhaps even an antidote to extremism based on false assertions. If people really know the truth, they can’t be carried away by hyperbole,” she says.

That, in a nutshell, is what this entire business is based on. There are signs that some of this thinking is being encouraged by the Modi government. The government has appointed Bhargava, who cites ancient Indian mathematicians like Aryabhatta and Brahmagupta among his inspirations, as the nodal person for a new initiative to get 1,000 U.S. academics to teach short-term courses, mainly in science and technology, at Indian colleges.

With the private and public sectors joining hands to reclaim the past, the next Science Congress will perhaps celebrate much more than apocryphal aeroplanes.