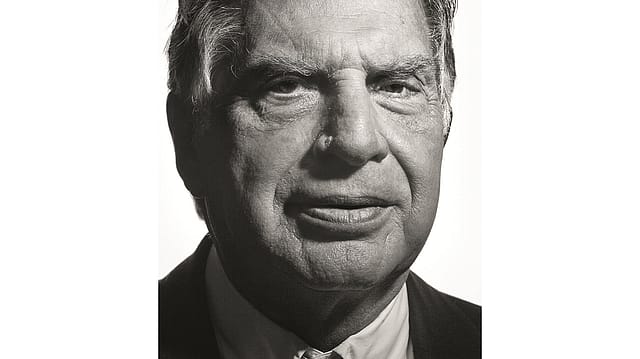

Ratan Tata: Business person of the decade

ADVERTISEMENT

Bakhtavar apartments is a somewhat unremarkable white washed block of flats opposite the Colaba post office, built in the 1950s close to Mumbai's southern-most tip adjoining the sea. Drive in and the first thing you see is that the somewhat letter ‘R’ on the signage on the building’s façade has come loose and flipped to the right. It’s a quick climb up a wide staircase to a wooden door that’s unpretentious—there’s not even a shiny nameplate on it—much like the occupant of the 3,000 square foot apartment it opens into.

When in Mumbai, its occupant is often spotted walking his German Shepherds, Titoo and Tango, in the lawns beneath his balcony. It’s a beautiful view from there. Some 40 metres ahead is the Arabian Sea, bound by rocks where Siberian seagulls flock every winter. In the distance, out on the water, you can see trawlers bobbing on the waves around Oyster Rock, a Navy establishment that once housed a museum.

Hiru Bijlani, a sixtysomething management consultant who lives in the flat across the landing, says his neighbour of nearly two decades “is private, somewhat reticent but never shy, and takes a little bit of time to open up”. Bijlani sometimes throws parties accompanied by loud, thumping music. His neighbour, he says, who listens to Western classical and jazz at a low volume (and counts Zubin Mehta and Amar Bose among his friends), has never complained. “He is a complete gentleman,” says Bijlani. It’s an opinion shared by many.

January 2026

Netflix, which has been in India for a decade, has successfully struck a balance between high-class premium content and pricing that attracts a range of customers. Find out how the U.S. streaming giant evolved in India, plus an exclusive interview with CEO Ted Sarandos. Also read about the Best Investments for 2026, and how rising growth and easing inflation will come in handy for finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman as she prepares Budget 2026.

Excruciatingly polite and soft-spoken, with a wry sense of humour, Ratan Naval Tata, 73, has few airs. In a nation where importance is measured by the size of one’s entourage, the chairman of the nearly $70 billion (Rs 3,18,640 crore) Tata empire discourages hangers-on, is forever saying ‘thank you’ and ‘please’ to his staff, still occasionally writes handwritten notes to his senior managers, and wears suits tailored in Mumbai and usually a Titan wristwatch with a white dial. Former Unilever director Ashok S. Ganguly who has known Tata intimately for more than four decades and sits with him on numerous bodies—including, most recently, the government-appointed Investment Commission, which Tata headed—says his leadership style is understated, and “he doesn’t need to constantly talk about himself on national media”.

Yet, this low-key approach belies a flinty, Horatius-like ability to stand his ground against grave odds and often shrill opposition, traits which have helped Tata prepare India’s largest, and one of its oldest, business empires for the 21st century. This reinvention of an old and unwieldy group that included a few unviable parts, and showing that conglomerates can succeed, is in itself a legacy-defining feat that made Tata Fortune India’s choice for Business Person of the Decade.

In 1991, when Tata took charge of the sprawling business house that bears his family name—founder Jamsetji Nusserwanjee Tata was his great-grandfather—it made a mere Rs 14,000 crore in sales. Over the past two decades, that figure has grown 22 times. There are 15 Tata companies on the Fortune India 500 list, and two (Tata Steel and Tata Motors) on the Fortune Global 500.

Bank of America Merrill Lynch’s country head for India Kaku Nakhate points out that the market capitalisation of the 28 listed Tata companies recently crossed $100 billion. “To this, add the value of unlisted stocks, and together they speak volumes about the Tata brand’s contribution to our economy.” These listed companies have yielded an annual average return of 30% in the past 10 years.

That said, Ratan Tata’s contribution, particularly in the new century, goes way beyond statistics. Cutting across industries and corporations, he has nearly single-handedly redefined the geographical boundaries of India Inc.’s ambitions. If meaningful globalisation is the foremost strategic imperative for Indian companies today, Tata is the trailblazer. He has shown how to build businesses globally, pull off big-ticket acquisitions, and most importantly, turn them around. In the process, he has come to define the new, emergent India.

Vijay Govindarajan, professor of international business at the Tuck School of Business, Dartmouth College, says Tata is India’s most admired face on the international business circuit, a bona fide heavy hitter with a status on par with other globally feted CEOs. He points out that, for some years now, GE’s Jeff Immelt has been trying to get Tata to address the group’s senior managers at its annual retreat in Boca Raton, Florida, where the likes of Apple’s Steve Jobs and Microsoft’s Bill Gates have featured in the past. “That tells me a lot about how his peers see him,” says Govindarajan.

Fellow academic Tarun Khanna at Harvard Business School says Tata’s efforts have changed how the West sees India. “I’d say the median Western attitude has evolved from being somewhat dismissive, to being grudgingly respectful, to perhaps exhibiting a competitive wariness.”

Tata has also shown the possibilities at the bottom of the pyramid, innovation, and of products developed primarily for India but suitable for similar markets around the world. Think Indica (especially remarkable at a time when other car makers were merely imitating their foreign counterparts), Nano, or Swach.

He’s done this by allowing managers a free hand. Rather than bullying or issuing fiats, he made them partners and helped them understand the principles behind his moves. Tata Motors vice chairman Ravi Kant says Ratan Tata acts more as a “facilitator and guide” than anything else. Ganguly calls this “Tata’s quiet innovation”: giving managers space to function, something few Indian promoters do.

Arun Maira, member of the Planning Commission and former chairman of Boston Consulting Group, India, who sat next to Tata at Bombay House (the group headquarters) in the late 1960s, once observed that it bothers Tata immensely when his CEOs say that “things are not very clear”. Tata’s response: If it gets any clearer, it’s no longer a principle, and it becomes inflexible.

Perhaps the only aspect of business he is inflexible about is how the group conducts itself. Zia Mody, founding partner of law firm AZB & Partners, who has worked with the Tatas on numerous deals, says he insists on doing what’s right, even if it slows things down.

Recently, after secretly recorded telephone conversations between him and lobbyist Niira Radia were leaked, Tata took the government to court for invasion of privacy (see interview on page 114). This, despite his abiding respect for the prime minister.

IN MANY WAYS, RATAN TATA IS AN UNLIKELY HERO, much as Rajiv Gandhi was an unlikely politician. Born in Mumbai on Dec. 28, 1937, Tata was brought up by his grandmother, because his parents got divorced when he was 7. It was a life of privilege. Indeed, some of Tata’s most embarrassing moments as a child were when the family limousine would be sent to fetch him from school. Often, he would send the car back and return home independently.

He studied architecture at Cornell University, briefly worked as an architect in California (he had rebelled: His father, Naval Tata, had wanted him to be a chartered accountant), fell in love with the U.S. and didn’t necessarily want to come back to India. He returned because his ailing grandmother wanted him to, and was soon thrown into the family business, starting out in Jamshedpur in 1962. Even then, Tata often thought of moving back to the U.S., but ultimately never did. In 1991, Jehangir Ratanji Dadabhoy (J.R.D.) Tata, who had been chairman of Tata Sons, the group’s holding company, since 1938, anointed him successor.

J.R.D. may have been prescient (in one interview, he had said that he picked Ratan Tata for his memory), but many thought Tata made the cut only because of his name.

Among them was Russi Mody, then chairman of Tata Steel. While Mody’s rebellion and subsequent ouster is part of corporate folklore, a little-known aspect of the skirmish bears special mention. The tussle with Mody is also the only time that Bombay House feared that the biggest company in the conglomerate might actually secede. In those days, the Tatas controlled barely 7% to 8% of Tata Steel. Mody’s efforts to lobby other shareholders came to nought. However, if he had succeeded, history (and Fortune India) may have judged Tata differently. Over the next few years, Tata Sons increased its stake in group companies.

RATAN TATA'S DECADE ACTUALLY BEGAN in the late 1990s, back against the wall, with most of his businesses (steel, chemicals, trucks, and so on) floundering in the midst of a bruising slowdown. Tata Motors’ position was particularly acute—not only had the commercial vehicles market shrunk by 40% (Tata Motors held on to its market share, though), but the Indica project was also soaking up significant capital. In 2001, Tata Motors declared a Rs 500 crore loss—unheard of in its 55-year history—with its stock at an all-time low of Rs 60. The markets blamed the Indica project for the company’s woes—a chairman’s folly, if you will—not seeing, perhaps, that the economic environment was doing more harm.

Early on, Tata saw the threat posed to his group if it depended only on one geography. It didn’t just come from being integrated into the global economy. The threat equally came from foreign companies who were setting up shop in India. According to Tata Sons director R. Gopalakrishnan, the way Ratan Tata saw it was: “Shape up and shop out—become best in class at home, and get a foothold abroad.”

He didn’t want token internationalisation—many dots all over the world and no significant presence anywhere. What he wanted was meaningful presence overseas, achieved through moves that fitted in with company strategy. For example, if Indian Hotels were to buy something abroad, the acquisition had to be seen through the filter of the hotel business, and not as real estate, as had been the case until then. There was also no mandate that acquisitions were the only way to grow abroad.

In 2000, an opportunity resurfaced to buy British tea maker Tetley. An earlier attempt had failed, but this time, there were no mistakes: Tata Tea picked up Tetley for £271 million (Rs 1,972 crore). It was a bold move: The company leveraged its balance sheet to do this, something unheard of in those days. Tata Sons director R.K. Krishna Kumar says the biggest lesson they learnt then was “how to use global financial markets to orchestrate such a deal”.

Strictly speaking, Tata wasn’t the impresario; Kumar (then vice chairman of Tata Tea) was. Tata merely threw his weight behind the deal—as he has done often since then. Tata Steel vice chairman B. Muthuraman has orchestrated all eight buyouts by his company, as have Ravi Kant, S. Ramadorai (the CEO of Tata Consultancy Service till October 2009), and others.

In the case of Jaguar Land Rover, for example, Ratan Tata learned that Ford was looking to exit. “In turn, he discussed it with me and the senior management,” says Kant. An internal study showed the Tata Motors team was confident, since they had done the Daewoo deal in 2004. A closer look at Jaguar spotlighted a mix of exciting new products, quality rankings, engineering ability to make its own vehicles, and a dedicated dealer network. Tata Motors snapped up the legendary automaker in June 2008 for $2.3 billion.

Many pronounced it a blunder, possibly spooked by the debt that funded the deal. “Everybody in India and outside said this was a disaster,” says Kant. “How could an Indian company with no experience take over two iconic British brands in an alien country?”

This wasn’t unusual: Dealing with naysayers has almost become a Bombay House tradition. Most of the moves that ultimately earned Tata acclaim were scorned at first. After Tata Steel bought Corus, the market beat the stock down. When Ratan Tata announced the plan to build a Rs 1 lakh car, everyone, including Osamu Suzuki, chairman of Suzuki Motor, said it wasn’t feasible. And so on.

Predictably, Jaguar Land Rover’s turnaround last year—sales were up 40% compared to the previous year—stunned the world. Tata Motors’ share price rebounded stupendously, from a low of Rs 131 in early 2009 to Rs 1,300 by end-2010. Says Vikram M. Thapar, vice chairman and joint managing director, KCT Coal Sales: “I had grave doubts about the JLR and Corus takeovers, and instructed my managers to exclude them (Tata Motors and Tata Steel) from my investment portfolio. I’m delighted that it was I who was proved wrong and not they.”

This capped a phenomenal decade for Tata—among other things, firming up the foundation of his companies when things looked the darkest, investing to build businesses overseas, geographically derisking the group (today around 60% of turnover comes from overseas, up from 24% in 2003), developing the small truck, Ace, and, of course, building the Nano.

This is not to say that Tata’s ventures have been uniformly successful. Though the group was one of the first to spot the opportunity in telecom in the mid-1990s, it has since struggled and its presence there in no way matches its dominance over other sectors like commercial vehicles, steel, or hotels. Similarly, Titan Industries’ early foray into Europe was a complete misadventure.

The group’s critics on Dalal Street also point out that the long debate over listing TCS—the idea was first mooted in 2000 and TCS listed in 2004—knocked a few thousand crores off the company’s final valuation. Hemendra Kothari, founder, DSP Financial Consultants, who took TCS public says Tata could have “easily charged Rs 25 higher per share”—it was offered in a price band of Rs 775 to Rs 900—but he didn’t, “because he wanted all investors to benefit”.

More recently, the Nano’s safety issues and falling sales have been a cause for concern, though in January 2011, things have improved on the back of new financing schemes.

Moreover, Tata has often taken the road less travelled—betting on Singur, for example, when nobody was willing to bet on West Bengal, or buying Jaguar Land Rover when there was a question mark over its future. Some of these decisions have been a strain on the group and its shareholders, and often polarised opinion. However, even Tata’s harshest critics concede that his bets were audacious and visionary.

Tata is of course the last person to claim that his journey was always smooth. After all, a juxtaposition of the highs and the lows has dogged him constantly. When he was made chairman, his ascendancy was questioned. He consolidated his position within the group and embarked on bold strategies, when the late-1990s slowdown ravaged his companies. He pulled off two extraordinary acquisitions—Corus and Jaguar Land Rover—only to be tripped by the global downturn. The Nano was unveiled to extraordinary appreciation, and the Singur fiasco followed. American President Barack Obama paid his respects to the victims of 26/11 at Mumbai’s Taj Mahal hotel and addressed India from there. Soon after, the Niira Radia tapes emerged.

Tata says he takes this to be his destiny. Ask him if spirituality plays a part in all this, and he laughs. Point out that on a shelf behind his desk are a glass-encased statue of the Buddha, and a Zarathustra icon. He says they’re gifts, and he doesn’t know where else to keep them. Mumbai’s Parsis say they sometimes see him at the city’s agiaries (fire temples).

SO, WHAT MAKES RATAN TATA TICK? His most feted innovation may offer some clues.

On a monsoon afternoon in Bangalore in 2002, he saw a family on a scooter skid just in front of his Mercedes. And the Nano was conceived. Similarly, in 2006, while being shown a contraption that TCS had built as a corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiative, Tata thought up the Swach water filter. TCS had erected a giant water purifier made of clay, which killed 85% of bacteria and which could be transported easily in the hinterland—especially useful in disaster relief operations. Tata asked his managers to figure out a way to make the water completely bacteria free, and to make the idea commercially viable.

Gopalakrishnan cites these examples to explain Tata’s ability to see things that others don’t. Where many would have seen just a rain-related accident or a CSR programme, Tata saw the possibility of products that would not only help society but also make money. Tata himself says there’s a bit of the “idiot inventor” in him—the little boy who played with Meccano sets, but more important, tried to adapt everyday items like scissors for left-handed people. “It’s just an old dream,” he says. “Is there another way to do something?”

Combine that with a willingness to ask really tough questions and a picture emerges of what helped Tata succeed. Unlike many of his peers like Mukesh Ambani,

N.R. Narayana Murthy, or Sunil Bharti Mittal, who built their businesses alone (or as in Ambani’s case, alongside his father, Dhirubhai) and, therefore, had the freedom to craft them from scratch, the companies that Tata came to head were mostly in place much before his ascension. What they needed was a man who was willing to be dispassionate in evaluating their future.

And Ratan Tata was more than willing to do that. Perhaps because of his early years outside the group, Tata admits that he often felt like an outsider inside the storied house of Tata and that allowed him to question the fundamentals of how the businesses functioned. For example, one of the things that played on his mind was the inherent competitiveness of the companies. So, he compared their efficiency with the best around the world. When Tata Steel claimed that it was one of the most cost-efficient producers of steel in the world, he turned around and reminded them that they had captive iron ore resources. But what if Tata Steel had to buy ore at market prices? Though Tata was seen as being unduly critical, it was these kinds of interventions that ultimately helped improve the efficiency of several Tata group companies and prepare them for the new century.

Ratan Tata also doesn’t shy away from taking tough decisions. In 1989, a couple of years before he took over as chairman, he had famously told striking trade unionists in Pune: “If you put a gun to my head, you had better pull the trigger or take the gun away, because I won’t move my head.” He broke the strike.

Nearly two decades later, head of the Trinamool Congress and incumbent Railway Minister Mamata Banerjee did pull the trigger, in a manner of speaking. Then the leader of West Bengal’s opposition party running an agitation against the Tatas’ small-car (Nano) project in Singur, Banerjee led protests over compensation to farmers for land, and things took a violent turn. Trinamool activists began attacking workers and managers at the Nano factory, which had cost the Tatas nearly $350 million to build. The party reckoned Tata would be a hostage to his investment and it would restrict his options. It was mistaken: He shifted base to Gujarat.

Former Mercedes-Benz India head Wilfried G. Aulbur (now with consultancy Roland Berger), who watched this from the sidelines, says West Bengal was a catastrophe. “Being forced to shift, in the auto business, means losing a lot of money and time. But he [Tata] had the courage to stick to his guns,” he adds.

Similarly, when the Corus turnaround demanded mothballing of the Teesside plant in Britain, which resulted in the loss of 6,000 to 7,000 jobs, Tata didn’t back down. It must be remembered that it’s not as if he takes all these decisions himself; they are mostly taken by his operating managers. But, as he says, he has never shied away from backing them to the hilt when necessary.

Muthuraman argues that Ratan Tata tends to spend more time on companies either when they are in crisis (in the late 1990s, for instance, he would spend days together in Jamshedpur, with the managers of Tata Steel), or when they’re working with high-end technology that would enable them to leapfrog the competition.

This ability to see both the big and the small is a Tata hallmark. Autocar India editor Hormazd Sorabjee says that in the Jaguar Land Rover deal, Tata bet on the company’s technical skills and product pipeline. Ramadorai, who has known Tata for over three decades, says he has an engineer’s mindset. “So, he’s got structure behind the thinking.”

Above all, Tata has the ability to think really big (Tetley was the biggest cross-border deal till then, as was Corus) while also being conscious that he could fail. When Kant rejoined the group in 2000 at Tata Motors (he had done a stint at Titan Industries some years earlier), Tata bluntly told him that he would be expected to do great things and “success may not be assured”.

A few years later, in the last stages of the bidding for Corus, which Tata, Muthuraman, and others were managing out of a suite at the Taj Mahal hotel in Mumbai, Muthuraman was asked to draft two press releases—one for use if they succeeded, and the other, if they failed. Muthuraman found it easy to write the press note announcing that Tata Steel had won, but the other one a challenge, and “had to be redrafted many times”, he says. It was almost as if he had to confront—or rather, anticipate—all the reasons why the bid had failed, and learn from them.

If Ratan Tata demands that his CEOs be deeply introspective, it’s because he himself is like that. Perhaps that has something to do with how he’s been perceived for years: He’s always underestimated.

His most publicised CEO stint before he became group chairman—one that still comes up for discussion—invariably got the wrong spin. In 1971, he had been made boss of Nelco (the National Radio and Electronics Company), a consumer electronics manufacturer. The company was in such bad shape that salaries were sometimes held up. Tata would often end up on the shopfloor, placating the workers and explaining the reasons for the delay. The facts that Tata nursed the company back to health, increased its market share from 2% to 20%, and began paying dividends are usually overlooked in the narrative. Unfortunately, labour problems cropped up later, and Nelco’s fortunes dipped once again. (Nelco still exists, but concentrates on industrial electronics now.)

A STONE'S THROW FROM BAKHTAVAR, Ratan Tata is building a house where he plans to live when he retires. He is the architect. He once worked for the architectural firm Jones and Emmons in Los Angeles, and has designed three houses in India—for a friend in Jamshedpur, for his mother in Mumbai, and his own shack in Alibaug.

He’s not sure what he’ll do once he steps down in December 2012, when he turns 75. He is drawn to the idea of doing something for the country, although he’s clear it won’t be politics. It may be something to do with young people. Another option is to play a role in a high-tech company such as Sun Catalytix, started by MIT professor Daniel Nocera. The company, in which the Tatas have a stake, seeks to develop a technology that makes it viable to generate energy by breaking down water.

One thing that he’s certain he won’t do is return to Bombay House. He says he wants his successor to have a free hand.

But how will the group fare without him? Gopalakrishnan argues that Ratan Tata has made the group “future-ready” as far as “people, products, and processes are concerned”. Kumar sees it differently. He believes that the challenges will be “significant”, and he keeps talking to Tata about it. However, given that the group’s foundations are secure, a worthy successor should be able to rise to them.

Those who know Ratan Tata well say he’s a terrific mimic. However, imitating his contributions to the Tata group, and to Indian industry in general, will be quite a challenge for any corporate leader.