The day of the last brand

ADVERTISEMENT

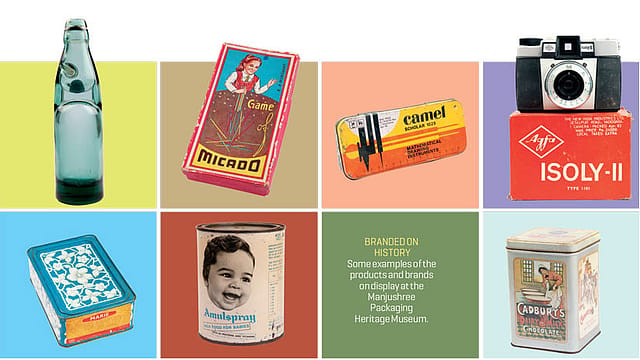

A MUSEUM DEVOID OF CULTURE VULTURES and tourists but filled with brand managers and marketing heads—sounds odd? These unique visitors make regular trips to study old labels and the evolution of packaging through the years.

In 2003, Vimal Kedia, managing director of Manjushree Technopak, a packaging solutions company, started the Manjushree Packaging Heritage Museum on 1,000 sq. ft. of his factory land in Bangalore’s Electronic City. He opened it to the public in 2010.

“I was inspired by a museum of computers and software on the Infosys campus that I visited in 2002,” says Kedia. He has spent more than Rs 50 lakh to build a collection of over 1,800 items, ranging from a 1930s glass bottle made by the U.S.-based packaging provider Ball Corporation to an old Britannia biscuit tin from the ’60s, to a jar of infant food of the 1980s with the iconic Amul baby on it. He also has the entire series of Coke and Pepsi packages, tracking their global changes in design through the decades.

“I source items from almost everywhere—antique shops in Mumbai, Delhi, the U.S., and even friends’ houses in Assam,” he says. He spends about Rs 5 lakh a year on upkeep, and doubles as the curator every Saturday, when it is open to the public. On other days, the museum can be visited by appointment.

He plans to expand it to 2,500 sq. ft. “It will have spot lighting suitable for such a museum with advanced displays, including sound bites on each brand’s history, a public address system, and professional curators” adds Kedia. There are two other such museums in the world: The oldest is on Portobello Road in Notting Hill, London, and the other is in an old church complex in Heidelberg, Germany. The Notting Hill museum was built by consumer historian Robert Opie in 1984, while the Heidelberg one came up 12 years later.

January 2026

Netflix, which has been in India for a decade, has successfully struck a balance between high-class premium content and pricing that attracts a range of customers. Find out how the U.S. streaming giant evolved in India, plus an exclusive interview with CEO Ted Sarandos. Also read about the Best Investments for 2026, and how rising growth and easing inflation will come in handy for finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman as she prepares Budget 2026.

The past depicted in the Manjushree Packaging Heritage Museum provides inspiration for many brands of top consumer companies. Executives from Kraft, Hindustan Unilever, PepsiCo, and Reliance Industries make it a point to visit to get new ideas.

According to Prabuddha Dasgupta, who retired as head of packaging development at Hindustan Unilever in May, the modern jars for the company’s Annapurna salt brand were inspired by displays in the museum, as was the packaging for Red Label and Taaza teas. “I ensured that brand managers from HUL regularly visited the museum to look at new additions to the collections,” he says. “It helps to look at the past and have concepts for the future.”

Kedia says their R&D team worked with Kraft to help re-design the new pack for Bournvita; what was helpful were the old designs displayed in the museum. Similarly, R.D. Udeshi, president, polyester division, Reliance Industries, has visited the museum numerous times with his team. “Packaging as an industry has become very dynamic and its transition in the last 20 years is fundamental to businesses today. We learn this from the museum,” says Udeshi.

Harish Bijoor, a consultant specialising in brands, applauds the idea. Over the next few years he plans to build memorials to dead brands. “We’ve forgotten where they came from. It’s important to study history, because it helps build perspective. For instance, the era of tin packaging is the most interesting.” This era was the first proper form of packaging, and lasted longest. Most brands gained popularity during that era. “The future could be edible packaging.”