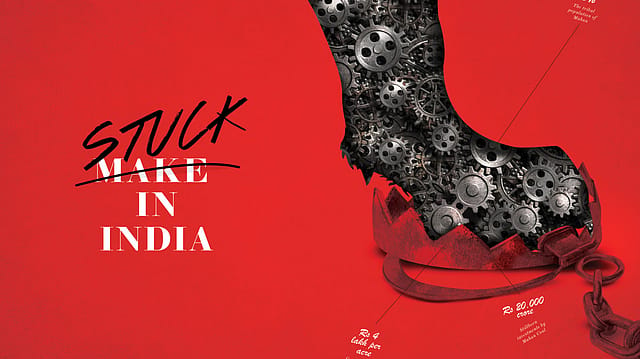

Mahan coal block: Stuck in India

ADVERTISEMENT

“Giving land for money ... that’s not what anybody wants. Compensation is not important. Everyone wants a job.” I am sitting on the edges of one of Asia’s densest sal forests with 60-year-old Bechan Lal Shah, who leads the Mahan Sangharsh Samiti, a village collective under the aegis of not-for-profit organisation Greenpeace. The Samiti has spent more than five years fighting a joint venture between Essar and Hindalco that wants to dig out 150 million tonnes of coal from Mahan, located in the Singrauli district of Madhya Pradesh. It claims that mining will destroy the local ecology and livelihoods. Meanwhile, the JV, which won the licence to operate the block in 2006, has pumped in nearly Rs 20,000 crore setting up power and aluminium plants, dependent mainly on Mahan’s coal.

Now, Shah, who has been to prison for his role in the fight, is telling me that the world outside has got the villagers’ pain point all wrong. While there’s a cacophony of views on what ought to be fair compensation for those who give up their land, he says the real crisis lies in their acute hunger for jobs. Shah himself owns two acres and has a family of 20 living off them. He is not happy with the compensation offered—Rs 4 lakh per acre—but his bigger worry is the havoc that the sudden spurt of money is wreaking on those who decided to sell. “Many of them ran through the cash in no time,” he tells me. “They frittered it all away.”Says 31-year-old Jag Narayan (five acres, eight family members): “Everyone who sold their land thought, ‘Now they will give me a job. The money is small, let me enjoy it. The job will take care of me.’”

To be sure, there would be only one job per family, and given the lack of technical skills among the region’s population, it would mostly involve menial labour. Shah and his fellow protesters say that’s a raw deal after the companies take away the forest that has sustained the villagers, and their dignity, for decades. However, in these parts chronically starved of development—about 40% of the people here are tribals, and their primary livelihood consists of gathering and selling mahua flowers that are pressed to make medicinal oil, biodiesel, and liquor—it isn’t easy to dismiss the lure of a job offhand.

But that tenuous dream has soured. Mahan is one of the 204 coal blocks allocated by the previous United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government that the Supreme Court recently cancelled, calling the allocation process “ad-hoc and casual”. The Modi government did not include it in the latest round of auctions that fetched close to Rs 2 lakh crore, stating that it lacked environment clearances. No one knows what the future holds for Mahan, or the plants that were supposed to create the jobs, fuelling growing despondency on the ground.

Despondency isn’t a new theme in India’s murky land-acquisition saga. Villagers who had signed away their land for the stillborn Tata Nano project in Singur, West Bengal, know the feeling well. There, current chief minister Mamata Banerjee led a bitter fight against the then communist government’s land acquisition plans, trapping in the margins those who had sold land in the hope that the project would bring jobs. Banerjee’s agitation forced the Tatas to relocate to Gujarat (where Prime Minister Narendra Modi was then chief minister), and also helped her overthrow the communists after a historic three-decade rule.

For the Modi government, the stakes are even higher. The impasse at Mahan is a symptom of what could go wrong with its grand Make in India campaign, which aims to make the country a global manufacturing power and is the lynchpin of Modi’s own political future. It’s also an alarm bell for the government’s plan to double coal production to 1 billion tonnes, helping the country become a net exporter from a net importer by 2019, and changing the lives of nearly 300 million Indians who have never used electricity.“India today is using the same amount of coal per capita that the U.S. was using in 1860. It is impossible for us to develop as a country at this level,” Minister for Power Piyush Goyal tells Fortune India. “We need to electrify, we need cheap power for manufacturing, for building ports, highways, massive infrastructure. We have the most ambitious green-energy plan in Indian history—we want to take solar-power generation from 20 GW to 100 GW and wind to 60 GW—but we also need the coal,” he says.

Simplifying land acquisition, including passing a new law that the government claims will balance the needs of industry with those of the affected people, will be central to all of this. But the opposition, subdued for most of the government’s first year in power, has begun to coalesce strongly against the law, leading to a stalemate in Parliament.

January 2026

Netflix, which has been in India for a decade, has successfully struck a balance between high-class premium content and pricing that attracts a range of customers. Find out how the U.S. streaming giant evolved in India, plus an exclusive interview with CEO Ted Sarandos. Also read about the Best Investments for 2026, and how rising growth and easing inflation will come in handy for finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman as she prepares Budget 2026.

Agriculture and food expert Devinder Sharma says, “Land is a naturally emotive issue. It swiftly brings people together, quite like inflation, because it has to do with the very basic necessity—food.” That’s at the heart of the lessons from Mahan, a complex minefield that can derail the best-laid plans.

I decide to travel to Mahan via the nearest big town, Varanasi, in Uttar Pradesh. Locals say it’s a six-hour drive, but in reality the car bumps and grazes for almost 10 hours. The road is primitive, but the area we are travelling to was meant to be a shining beacon of development. Since the late 1970s, Singrauli has been home to some of India’s biggest electricity projects. The National Thermal Power Corporation has three major electricity stations here. Plans for at least another 10 have been drawn up as the area has one of the biggest coal deposits in India, spread across 2,000 sq. km. Lignite, the form of coal extracted from this area, serves power plants in three states—Delhi, Haryana, and Rajasthan. All this has given Singrauli the moniker ‘Energy Capital of India’.

But talk to villagers, and you hear the complaints that have been the scourge of the Indian countryside for decades: hardly any schools, pathetic transport and communication, ramshackle health care, and a ceaseless hunt for jobs.

In 2006, there was new hope as Mahan Coal, the Essar-Hindalco JV, set up base in the area. The company planned to mine 8.5 MTPA (metric tonnes per annum) of coal—5.1 MTPA for Essar and 3.4 MTPA for Hindalco. Essar would use the coal for a 1,200 MW power plant. Hindalco planned a 650 MW power plant as well as an aluminium smelter.

The area affected by the mine has a population of about 14,000, though some estimates suggest the real number is a little over a third of that. As is often the case in the “development vs. displacement” debate, the numbers are far from clear. What is clear is that the locals welcomed the JV at first. Even Shah of the Samiti accepts that. “For some time, everyone was excited,” he says. You can still see the shuttered shells of sewing centres, part of Mahan Coal’s skill-development drive. “A lot of people were going to be trained in various things, including factory work, but it never happened,” says a villager who points out the relics to me.

There was going to be more—notably, schools and dispensaries—but even after the JV received environmental clearance in 2008, a series of forest advisory committees remained divided on whether it should be given the final go-ahead. In 2010, with Jairam Ramesh as environment minister, Mahan was declared a “no-go” zone. The ministry first wanted to identify the pockets that needed to be completely barred from mining activity in order to protect the region’s rich biodiversity. Essar wrote to the office of then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh that even though 65% of its plant was ready, there was no final forest clearance in sight.

By this time, even the PM’s office accepted that at least Rs 3,600 crore had been sunk into the project. Sushil Maroo, managing director and CEO of Essar Power, tells me that in interest payments alone such projects cost Rs 70 lakh to Rs 1 crore per megawatt. “As more and more time is lost, there is great pressure from lenders,” says Maroo. The fiasco became a classic demonstration of why India has long languished at the bottom of the World Bank’s ‘Ease of Doing Business’ rankings.

When I wrote to Ramesh asking to speak to him, he pointed me towards his writings on the subject. In his letters to Singh in 2010, Ramesh accepts that the Mahan coal block was allocated before the no-go zone policy came into being, but argues that the block had been allocated before all the necessary forest clearances

were taken.

Soon, rival groupings of villagers for and against the mines started appearing in Mahan, further muddying the waters. The Mahan Vikas Manch, which opposes the Samiti, petitioned the villagers that this was their last chance to get desperately needed development. (The Manch argued, among other things, that for the 500,000 trees that would be cut, 6.9 million new ones would be planted.)

“NGOs don’t see people,” Sanjay Thakur of the Manch tells me angrily. “They only see trees, but people need more than trees. We can’t survive by selling mahua! Make in India should also mean we can make what we want of our lives.”

But India is not ready for Make in India, claims Priya Pillai, the Greenpeace activist who made news when she was refused permission to board a flight to London to make a presentation about the London Stock Exchange-listed Essar before British parliamentarians. (Shortly after our visit to Mahan, the government blocked Greenpeace India’s accounts and their clearance to receive foreign funds. It accused Greenpeace, which has had run-ins with several governments including Canada and New Zealand, of obstructing India’s developmental process. Later, the Delhi High Court allowed it to use its two domestic accounts to receive domestic donations.)

Pillai points out that India’s Forest Rights Act demands that forest communities give approvals via gram sabhas for disruptive and displacement activities like mining. At Mahan, a gram sabha resolution was duly passed—but it later turned out to have numerous fake signatures. “The trouble is that when we talk about assets, we only evaluate the assets of the rich and never those of the poor,” says Pillai. “What the poor lose is never taken into account.” Even in the polarised sides within Mahan, there is this class divide. The Samiti is mainly made up of villagers who own no land and only use forest resources, or people like Shah who own very little and often fractured land parcels. The pro-mining Manch, on the other hand, draws its membership mainly from those with larger land holdings.

Pillai’s argument about accounting for the assets of the marginalised isn’t just a socialist plea. It has scholarly validity within the realms of free-market economics: Consider the works of the Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto, who writes that a market economy cannot function well if the assets of the poor are not valued properly.

The greatest hurdle to Make In India might well be embedded in that thought. Community assets, forests in this case, need proper assessment—including their emotional value to the community—for Modi’s cherished development juggernaut to roll without conflict. While jobs are the ultimate expectation in a land transaction, often the immediate deliverable is monetary compensation. And money without credible evaluation of the asset will never be enough. Often governments only pay lip service to this principle and end up antagonising local stakeholders, who resent what they perceive as an arbitrarily decided quid pro quo thrust on them.

When I ask Goyal, the minister for power, about this challenge, he gives me a short, pointed response: Development can no longer be held hostage. “Some people are just against development,” he says. “The nation can no longer suffer them.”

For all the tough talk, land acquisition is fast becoming an albatross for the Modi government. As one Congress Member of Parliament tells me, “Land is the new communalism.”

Over nearly two decades following the fall of the Babri Masjid, the biggest opposition plank against the Bharatiya Janata Party has been communalism—accusing it of pitching Hindus against minority communities like Muslims and Christians. But after Modi’s landslide victory in 2014 and the BJP’s creditable showing in the Kashmir assembly polls where it’s one half of a coalition government, there is increasing realisation within the Congress and other major opposition parties that this pitch is no longer as relevant. With polls scheduled in critical states like Bihar and Uttar Pradesh in the next two years, land acquisition seems to be getting a far more powerful response. That’s why the Congress used this issue to relaunch Rahul Gandhi after his sabbatical, in and outside Parliament.

Protests in different parts of the country, which have seen tribals defecating on the bill in Jharkhand and taking out agitated rallies in Punjab, have strengthened the opposition’s hand. Delhi-based research agency Society for Promotion of Wasteland Development estimates an increase of 40% in land-related disputes since last year.

Economist Rajiv Kumar says it does not need to be this way. He says he supports the new land bill because “most manufacturing needs less than 100 acres and there are millions of farmers in India who are trapped with holdings of less than one acre. This could be a win-win.”

Kumar says he is astonished that in the entire debate on Mahan, one fundamental question has never been addressed: Why can’t the mines be underground? “China mines around 4 billion tonnes of coal a year, and around 86% is through underground mining which does not do much damage to the environment,” he says. “It is slightly more expensive, but if you take into account the ecological and displacement costs, it is far more efficient.”

Another criticism of policy has been that it usually makes the mines “captive”, allowing them to be used only by plants in the region. The companies owning the mines aren’t free to trade the coal, which would make the market for coal more open. “We are not here to work for better profits,” counters Goyal. “What do I do with the power plants that are starved of coal?”

Back at the sal forests, Sanjay Thakur mourns a lost cause. “Who knows when there will be a mine. Till then, no jobs,” he sighs. Rival Shah is happier, but it’s a fragile happiness. “We have won for now,” he says. “But our young need those jobs.”

Despondency isn’t a new theme in India’s murky land-acquisition saga. Villagers who had signed away their land for the stillborn Tata Nano project in Singur, West Bengal, know the feeling well. There, current chief minister Mamata Banerjee led a bitter fight against the then communist government’s land acquisition plans, trapping in the margins those who had sold land in the hope that the project would bring jobs. Banerjee’s agitation forced the Tatas to relocate to Gujarat (where Prime Minister Narendra Modi was then chief minister), and also helped her overthrow the communists after a historic three-decade rule.

For the Modi government, the stakes are even higher. The impasse at Mahan is a symptom of what could go wrong with its grand Make in India campaign, which aims to make the country a global manufacturing power and is the lynchpin of Modi’s own political future. It’s also an alarm bell for the government’s plan to double coal production to 1 billion tonnes, helping the country become a net exporter from a net importer by 2019, and changing the lives of nearly 300 million Indians who have never used electricity.“India today is using the same amount of coal per capita that the U.S. was using in 1860. It is impossible for us to develop as a country at this level,” Minister for Power Piyush Goyal tells Fortune India. “We need to electrify, we need cheap power for manufacturing, for building ports, highways, massive infrastructure. We have the most ambitious green-energy plan in Indian history—we want to take solar-power generation from 20 GW to 100 GW and wind to 60 GW—but we also need the coal,” he says.

Simplifying land acquisition, including passing a new law that the government claims will balance the needs of industry with those of the affected people, will be central to all of this. But the opposition, subdued for most of the government’s first year in power, has begun to coalesce strongly against the law, leading to a stalemate in Parliament.

Agriculture and food expert Devinder Sharma says, “Land is a naturally emotive issue. It swiftly brings people together, quite like inflation, because it has to do with the very basic necessity—food.” That’s at the heart of the lessons from Mahan, a complex minefield that can derail the best-laid plans.

I decide to travel to Mahan via the nearest big town, Varanasi, in Uttar Pradesh. Locals say it’s a six-hour drive, but in reality the car bumps and grazes for almost 10 hours. The road is primitive, but the area we are travelling to was meant to be a shining beacon of development. Since the late 1970s, Singrauli has been home to some of India’s biggest electricity projects. The National Thermal Power Corporation has three major electricity stations here. Plans for at least another 10 have been drawn up as the area has one of the biggest coal deposits in India, spread across 2,000 sq. km. Lignite, the form of coal extracted from this area, serves power plants in three states—Delhi, Haryana, and Rajasthan. All this has given Singrauli the moniker ‘Energy Capital of India’.

But talk to villagers, and you hear the complaints that have been the scourge of the Indian countryside for decades: hardly any schools, pathetic transport and communication, ramshackle health care, and a ceaseless hunt for jobs.

In 2006, there was new hope as Mahan Coal, the Essar-Hindalco JV, set up base in the area. The company planned to mine 8.5 MTPA (metric tonnes per annum) of coal—5.1 MTPA for Essar and 3.4 MTPA for Hindalco. Essar would use the coal for a 1,200 MW power plant. Hindalco planned a 650 MW power plant as well as an aluminium smelter.

The area affected by the mine has a population of about 14,000, though some estimates suggest the real number is a little over a third of that. As is often the case in the “development vs. displacement” debate, the numbers are far from clear. What is clear is that the locals welcomed the JV at first. Even Shah of the Samiti accepts that. “For some time, everyone was excited,” he says. You can still see the shuttered shells of sewing centres, part of Mahan Coal’s skill-development drive. “A lot of people were going to be trained in various things, including factory work, but it never happened,” says a villager who points out the relics to me.

There was going to be more—notably, schools and dispensaries—but even after the JV received environmental clearance in 2008, a series of forest advisory committees remained divided on whether it should be given the final go-ahead. In 2010, with Jairam Ramesh as environment minister, Mahan was declared a “no-go” zone. The ministry first wanted to identify the pockets that needed to be completely barred from mining activity in order to protect the region’s rich biodiversity. Essar wrote to the office of then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh that even though 65% of its plant was ready, there was no final forest clearance in sight.

By this time, even the PM’s office accepted that at least Rs 3,600 crore had been sunk into the project. Sushil Maroo, managing director and CEO of Essar Power, tells me that in interest payments alone such projects cost Rs 70 lakh to Rs 1 crore per megawatt. “As more and more time is lost, there is great pressure from lenders,” says Maroo. The fiasco became a classic demonstration of why India has long languished at the bottom of the World Bank’s ‘Ease of Doing Business’ rankings.

When I wrote to Ramesh asking to speak to him, he pointed me towards his writings on the subject. In his letters to Singh in 2010, Ramesh accepts that the Mahan coal block was allocated before the no-go zone policy came into being, but argues that the block had been allocated before all the necessary forest clearances

were taken.

Soon, rival groupings of villagers for and against the mines started appearing in Mahan, further muddying the waters. The Mahan Vikas Manch, which opposes the Samiti, petitioned the villagers that this was their last chance to get desperately needed development. (The Manch argued, among other things, that for the 500,000 trees that would be cut, 6.9 million new ones would be planted.)

“NGOs don’t see people,” Sanjay Thakur of the Manch tells me angrily. “They only see trees, but people need more than trees. We can’t survive by selling mahua! Make in India should also mean we can make what we want of our lives.”

But India is not ready for Make in India, claims Priya Pillai, the Greenpeace activist who made news when she was refused permission to board a flight to London to make a presentation about the London Stock Exchange-listed Essar before British parliamentarians. (Shortly after our visit to Mahan, the government blocked Greenpeace India’s accounts and their clearance to receive foreign funds. It accused Greenpeace, which has had run-ins with several governments including Canada and New Zealand, of obstructing India’s developmental process. Later, the Delhi High Court allowed it to use its two domestic accounts to receive domestic donations.)

Pillai points out that India’s Forest Rights Act demands that forest communities give approvals via gram sabhas for disruptive and displacement activities like mining. At Mahan, a gram sabha resolution was duly passed—but it later turned out to have numerous fake signatures. “The trouble is that when we talk about assets, we only evaluate the assets of the rich and never those of the poor,” says Pillai. “What the poor lose is never taken into account.” Even in the polarised sides within Mahan, there is this class divide. The Samiti is mainly made up of villagers who own no land and only use forest resources, or people like Shah who own very little and often fractured land parcels. The pro-mining Manch, on the other hand, draws its membership mainly from those with larger land holdings.

Pillai’s argument about accounting for the assets of the marginalised isn’t just a socialist plea. It has scholarly validity within the realms of free-market economics: Consider the works of the Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto, who writes that a market economy cannot function well if the assets of the poor are not valued properly.

The greatest hurdle to Make In India might well be embedded in that thought. Community assets, forests in this case, need proper assessment—including their emotional value to the community—for Modi’s cherished development juggernaut to roll without conflict. While jobs are the ultimate expectation in a land transaction, often the immediate deliverable is monetary compensation. And money without credible evaluation of the asset will never be enough. Often governments only pay lip service to this principle and end up antagonising local stakeholders, who resent what they perceive as an arbitrarily decided quid pro quo thrust on them.

When I ask Goyal, the minister for power, about this challenge, he gives me a short, pointed response: Development can no longer be held hostage. “Some people are just against development,” he says. “The nation can no longer suffer them.”

For all the tough talk, land acquisition is fast becoming an albatross for the Modi government. As one Congress Member of Parliament tells me, “Land is the new communalism.”

Over nearly two decades following the fall of the Babri Masjid, the biggest opposition plank against the Bharatiya Janata Party has been communalism—accusing it of pitching Hindus against minority communities like Muslims and Christians. But after Modi’s landslide victory in 2014 and the BJP’s creditable showing in the Kashmir assembly polls where it’s one half of a coalition government, there is increasing realisation within the Congress and other major opposition parties that this pitch is no longer as relevant. With polls scheduled in critical states like Bihar and Uttar Pradesh in the next two years, land acquisition seems to be getting a far more powerful response. That’s why the Congress used this issue to relaunch Rahul Gandhi after his sabbatical, in and outside Parliament.

Protests in different parts of the country, which have seen tribals defecating on the bill in Jharkhand and taking out agitated rallies in Punjab, have strengthened the opposition’s hand. Delhi-based research agency Society for Promotion of Wasteland Development estimates an increase of 40% in land-related disputes since last year.

Economist Rajiv Kumar says it does not need to be this way. He says he supports the new land bill because “most manufacturing needs less than 100 acres and there are millions of farmers in India who are trapped with holdings of less than one acre. This could be a win-win.”

Kumar says he is astonished that in the entire debate on Mahan, one fundamental question has never been addressed: Why can’t the mines be underground? “China mines around 4 billion tonnes of coal a year, and around 86% is through underground mining which does not do much damage to the environment,” he says. “It is slightly more expensive, but if you take into account the ecological and displacement costs, it is far more efficient.”

Another criticism of policy has been that it usually makes the mines “captive”, allowing them to be used only by plants in the region. The companies owning the mines aren’t free to trade the coal, which would make the market for coal more open. “We are not here to work for better profits,” counters Goyal. “What do I do with the power plants that are starved of coal?”

Back at the sal forests, Sanjay Thakur mourns a lost cause. “Who knows when there will be a mine. Till then, no jobs,” he sighs. Rival Shah is happier, but it’s a fragile happiness. “We have won for now,” he says. “But our young need those jobs.”