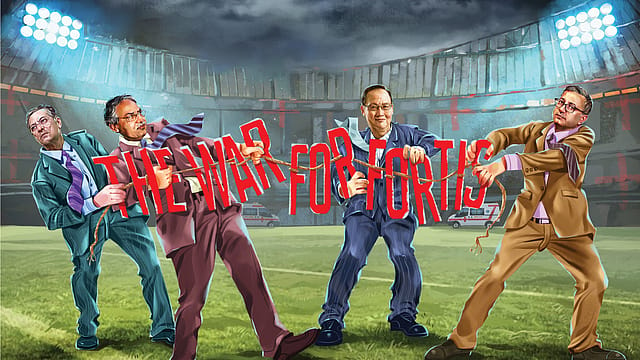

The war for Fortis

ADVERTISEMENT

There’s a gorgeous wooden staircase in my line of sight, and right through my meeting I wonder where it leads. I don’t ask, and definitely don’t climb up when my hosts leave me for a few minutes; I’m scared that it will be too rude. But I still wonder where it leads. Sunil Kant Munjal, chairman of the Hero group, and Anand C. Burman, chairman, Dabur india, don’t seem to have the same qualms. They saw a staircase, and climbed, not knowing if there’s a room at the top or if there’s just a steep drop into nothingness. Of course, the stairs they took are metaphorical—leading to India’s second-largest hospital chain, Fortis healthcare. as things are turning out, they seem to have climbed into a complex maze.

I’m sitting in Munjal’s sprawling home in Delhi’s Friends Colony, where Munjal and Burman meet me to talk of their Rs 1,800 crore bid for Fortis. A bid that had won them Fortis—that is, at the time of our meeting. There’s been so much happening since then, it has left all of us following the company gasping. In a nutshell, at the time of going to press, the Munjal-Burman bid was “mutually terminated”, and Fortis announced a fresh round of bidding.

The entire Fortis saga is so complicated and murky, it makes Game of Thrones seem like a simple bedtime story (minus all the blood and gore, of course). The Cliff Notes version goes something like this: Fortis Healthcare, a hospital chain in deep financial trouble, was put up for sale after much legal wrangling. The board opened the company for bids and selected the successful bidder, but was then accused of bad corporate governance practice. Three board members resigned, and another was asked to leave. Three new board members were inducted, and a fresh round of bidding announced. The winning bidder will end up owning a stake in Fortis in line with the total funds infused into the company.

So far, so simple. Except, of course, nothing is ever simple, particularly if it has to do with the erstwhile promoters of Fortis, Malvinder Mohan Singh and Shivinder Mohan Singh. The brothers have been accused of siphoning off Fortis funds. That’s apart from the legal quagmire they are already in, but more on that later.

The first bid for Fortis was received early this year from Bengaluru-based Manipal Health Enterprises, backed by U.S. private equity firm TPG Capital. The board had accepted this offer, but some shareholders objected, saying that the process should be transparent and opened up so better offers could be received. Bidding was thrown open, and three bidders seemed serious; two others made non-binding offers and were not taken into account. The three finalists, so to speak, were the Munjal-Burman combine, Manipal-TPG, and IHH Healthcare, a Malaysian healthcare major. The board announced that it was accepting the Munjal-Burman offer.

“We are providing the company exactly what the Fortis board had wanted,” explains Burman. “They did not want any due diligence, no conditionalities, and a quick infusion of funds to save Fortis Healthcare—its patients, doctors nurses and others—and a plan that would benefit all the shareholders. And we are doing exactly that.”

If only things were as straightforward. Despite winning (at the time), Munjal and Burman are dissatisfied at the way bidding was conducted. The deadline for submitting bids was May 1, but the Manipal group was given an extra five days; because the board had broken its earlier acceptance, it offered Manipal the “right to match” the other bids received. Munjal and Burman are annoyed that Manipal-TPG made a revised offer even later, on May 14. “To make another improved offer after the deadline seems odd, strange, and a little unfair,” says Munjal.

Ranjan Pai, CEO and managing director of Manipal Education and Medical Group, counters this saying the extended deadline was because he had a binding bid. Manipal-TPG, in a letter to Fortis, said it was clear investors were dissatisfied with the Munjal-Burman bid. More telling, it added that the Munjal-Burman bid may not get the approval of 75% of the shareholders; “it is likely to be very challenging for the Fortis board” .

Munjal disagrees, saying the bid he and Burman had made was the highest. And let’s not forget the bidder who actually did offer the highest amount, albeit with strings attached, IHH Healthcare. We’ll get to those bids soon, but there’s a lot more that led to a whole new round of bidding, which has not started at the time of going to press.

The board announced the winning bid on May 10, and a general body meeting should have been called for to get shareholder approval. Even earlier on April 20, two key minority shareholders, East Bridge and Jupiter Asset Management, which together hold a little over 12% in Fortis, complained of corporate governance issues and called for an extraordinary general meeting on May 22. They demanded the removal of four existing board members and appointment of three new ones.

Three board members stepped down before the EGM, another was asked to leave after the meeting, three new board members have since been inducted, other shareholders have expressed unhappiness, Shivinder Singh has stirred the pot accusing board members of not keeping shareholders’ interests in mind, bidders have been sniping at each other, and now, a new round of bidding has been started.

Confused? Things are going to get a lot more complicated before this entire episode ends. There’s a constant barrage of news coming out of Fortis; the media isn’t helping, with report upon report, all claiming to be “breaking news” or the “inside story”. It’s a cacophony out there already, but we think it’s just beginning to crescendo.

Before getting to the brothers and their involvement in all this, it may be worthwhile to look at what the board offered the three shortlisted bidders. In its letter to the stock exchanges, the Fortis board says it is inviting the Munjal-Burman combine, Manipal-TPG, and IHH Healthcare to participate in the new round of bidding. It has also invited expressions of interest from other interested bidders.

We spoke to several people close to this process, and they all say the three original bidders are the real contenders; a couple of them do add that it’s likely that Radiant Life Care, a hospital chain backed by global investment giant KKR, will submit an expression of interest. Radiant was one of the original five bidders, but was one of the two that were rejected for making nonbinding offers (Chinese conglomerate Fosun was the other).

If we look at the price each bidder had offered, it appears that IHH Healthcare is the clear winner; the Malaysian chain was willing to shell out Rs 4,000 crore for Fortis. “Our proposal,’’ says Tan See Leng, managing director and CEO of IHH Healthcare, “to invest Rs 4,000 crore at Rs 175 per share is one that is simple, holistic and compelling and comprehensively addresses the short-term financing needs and long-term strategic objectives of Fortis.”

It’s getting a bit repetitive to say things are not as simple as they seem, but it has to be said again. Because the IHH bid, says Munjal, offers “not more than Rs 175” a share, while the Munjal-Burman combine offered “at least” Rs 172 (by way of a combination of preferential eq - uity and preferential warrants). More important, IHH came in with a “go, no-go” clause; it offered Rs 650 crore upfront, but the remaining would come in subject to the results of a seven-day due diligence process.

“How could the board or the EAC [the ex - pert advisory committee] select such a bidder when it is not clear whether that entity will continue after the seven-day due diligence? In case it decides otherwise, it would mean starting the rebidding process again, a luxury that Fortis cannot afford,” a person closely connected with the process had said at the time. Moreover, he added, Rs 650 crore was too small an amount to take care of the immediate needs of the hospital chain.

IHH Healthcare, however, maintains that it had already taken the EAC’s feedback into ac - count by shortening the period of due diligence from the three weeks it originally sought, to just seven days. But then due diligence is a must “because as a dual-listed company on the stock exchanges of Malaysia and Singapore, we are accountable to our shareholders to be prudent in our decisions, in line with our strong corporate governance values”, says Tan.

Manipal’s Pai, meanwhile, claims that his bid was actually the best. In its final bid, made way past the deadline, Manipal raised the bid value of shares from Rs 160 per share to Rs 180, there - by valuing the company at Rs 9,403 crore from the earlier Rs 8,353 crore. Also, unlike the other two bidders, Manipal-TPG had added an offer to buy subsidiary SRL Diagnostics as well. The other two had few plans for SRL Diagnostics other than offering some sort of exit to investors. Manipal-TPG’s combined offer for Fortis and SRL comes to Rs 3,300 crore, of which Rs 1,200 crore was to go towards settling the private equity investors in SRL. “In our view, we had the strongest bid... We had committed more capital than Munjal-Burman,” says Pai.

The Delhi businessmen, meanwhile, are still convinced that theirs was the best deal. In fact, in a letter to the company on May 28 (the begin - ning of the new bidding saga), the two had writ - ten: “While we continue to be of the firm view that our offer is the best offer received by the company till date, we believe that this situation may have arisen largely on account of the lack of information available to stakeholders.”

The Munjal-Burman combine had bid Rs 1,800 crore, through Rs 800 crore of preferential equity at Rs 167 per share and Rs 1,000 crore through preferential warrants at Rs 176 per share; of this, Rs 1,050 crore was to have been paid up-front. “We had written to the board saying that once the deal is finalised, we will im - mediately infuse Rs 1,050 crore into Fortis, ap - point three members on the board, and provide the rest of the funds within the next four months or even earlier depending on the need of the company,” says Munjal.

The numbers are open to scrutiny, but there are other factors that the board took into account as well. Mainly, due diligence. The Fortis pro - moters have been accused of siphoning off com - pany funds into personal accounts, leading to the other bidders seeking time for due diligence. The Munjal-Burman combine, however, claimed that it did not need to inspect the books since Fortis needed money urgently. Also, with a combined 3.5% stake, they have been minority sharehold - ers of Fortis, so both Munjal and Burman say they know what they need to know about the company: that the worst is behind Fortis.

While the bidding war itself is fodder enough for a book, the back story is worth a movie. There’s a saying across cultures: “Shirtsleeves to shirtsleeves in three generations”, or, if you’re Japanese, “rice paddies to rice paddies in three generations”. In Scotland, they say “The father buys, the son builds, the grandchild sells, and his son begs”, while in China, they are more succinct: “Wealth never survives three generations.” The Brothers Singh seem to be living out that saying.

Fortis was set up in 1996 as an extension of Ranbaxy, the pharmaceuticals giant built by Bhai Mohan Singh in the 1950s. Ranbaxy itself has been at the centre of much controversy and family drama, much of it played out in the public eye. By 1989, Bhai Mohan Singh was ready to hand Ranbaxy over to his eldest son, Parvinder Singh, which made his other two sons unhappy.

Analjit Singh, the youngest of the three, had met me years later and sounded bitter about this division. “In the family settlement, the family gold, Ranbaxy, went to my eldest brother [Parvinder Singh, who died in 1999], the family silver, all the real estate assets, went to my other brother [Bhai Manjit Singh]. All I got was a factory at Okhla, where I had to offer VRS to the workers out of my own pocket,” he told me.

Parvinder Singh, after some bitter boardroom wrangling, got Bhai Mohan Singh ousted from the day-to-day functioning of Ranbaxy. More, when Parvinder Singh died (he predeceased his father), he left a will saying Ranbaxy should be run by a professional manager and not by the family. The funeral ceremonies were barely done when Bhai Mohan Singh wrote to the Ranbaxy board, urging members to put his grandson Malvinder Singh in charge, keeping Ranbaxy with the family. Malvinder Singh, however, claimed that he would honour his father’s wishes and refused to step into management, angering his grandfather in the process. By all accounts, Bhai Mohan Singh died an embittered man, leaving nothing to Malvinder and Shivinder Singh. His will was contested and the brothers got control of Ranbaxy, which they proceeded to run to the ground.

The Ranbaxy story is way too murky and convoluted to get into here. But we need to touch on the major points, because much of the current Fortis imbroglio has its roots in Ranbaxy and its one-time owner, Daiichi Sankyo. The extremely edited version of the story is that the Brothers Singh sold 64% of Ranbaxy to Daiichi for $4.6 billion in 2008; that included their 34.82% stake for $2.4 billion. Daiichi, on its part, trusted the brothers (as we found when we wrote about the deal back then, that’s an extremely Japanese trait) and did little by way of due diligence. Al - most as soon as the deal had been signed, issues with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) surfaced; Daiichi realised that it had been sold a lemon.

The Japanese company did try to make a go of Ranbaxy but things broke down pretty quickly. In 2012, Daiichi filed a case with the International Court of Arbitration in Singa - pore, claiming that the brothers had deliberately hidden key facts about the U.S. FDA investigations into Ranbaxy. The Singapore court ruled in favour of Daiichi, and directed the Singhs to pay Rs 2,563 crore in damages, plus interest of 4.44% a year from November 7, 2008 till the date of the award. (For the record, Daiichi sold Ranbaxy to Sun Pharmaceutical Industries for $3.2 billion in 2014, at a far lower price than it paid for the company in 2008.)

Ever since, Daiichi has been in court, seeking to bar the Singhs from selling any of their assets including Fortis and Religare, till they paid what the Singapore court had ordered, a total of Rs 3,500 crore. Daiichi, in the Delhi High Court last year, claimed that the Singh brothers were looking to exit Fortis Healthcare, which would hamper recovery of damages. In February this year, the Delhi High Court upheld the Singapore arbitration award; the brothers resigned as directors of Fortis, and have now approached the Supreme Court. Later that month, the Supreme Court allowed institutional shareholders to sell the pledged shares of Malvinder Singh in Fortis.

“Daiichi Sankyo, since long, has been making all possible efforts to try and sabotage the Fortis deal,” says Malvinder Singh. “Their constant blocking of any economically accretive proposals goes to show that their objective and motive is not to secure their award but being vindictive in nature to hurt the larger shareholders and employees. Their repeated actions have negatively impacted all Indian banks, all our shareholders and employees.”

One of those “economically accretive proposals” was from IHH Healthcare. It had bid for Fortis in June last year, before Daiichi went to court. At that time, IHH was to take a 26% stake in Fortis for Rs 3,600 crore, valuing Fortis Healthcare and SRL Diagnostics (which has 376 labs and over 6,300 collection centres) at $2.9 billion or Rs 19,000 crore.

So why does everyone want Fortis? The short answer is that it is India’s second largest healthcare company, with a network of 31 hospitals in 15 cities across India and 3 overseas in Mauritius, Uganda, and Sri Lanka. True, Fortis has reported net losses in three of the last five years. In fact, the company had been off investors’ radar because of its decision to acquire discrete international businesses across different geographies and trying to integrate them, thus stretching its balance sheet. On September 20, 2011, when Fortis International merged its domestic business, debt soared to over Rs 7,000 crore. It was only after the debt reduced to a manageable Rs 2,300 crore through a stake sale in what was then Super Religare Laboratories (SRL), divestment in Dental Corporation, listing of Religare Healthcare Trust (RHT), and the management’s promise to adopt an asset-light model in the future, that investors returned to Fortis.

Mumbai-based brokerage Edelweiss explains why Fortis is such a prized asset despite its troubles. In a report dated March 23, 2018, it noted that Fortis reported an average revenue per bed of Rs 40,000, the highest in the industry in India. It also reported the best gross margin—80%—among top-end hospitals, which is a function of the average revenue per bed to the therapy mix. “You also don’t get a well-built asset like this with low promoter holding,” explains Pai. The Singhs hold around 0.77%.

Moreover, since Fortis has nearly 52% of its doctors as visiting doctors, compared to just 5% for Apollo, it manages clinician costs better because it becomes a variable cost. Again, its earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation (Ebitda) margin has increased by 1,000 basis points in the past five years—from five in FY13 to 15 in FY17.

Back in 2016, when Fortis was in the throes of a global acquisition spree, I had spoken to Malvinder Singh, then executive chairman of Fortis, about his plans for the healthcare heavyweight. “In 15 to 20 years, we will not only use our cross-country learnings to be present across all categories of healthcare delivery—from diagnostics to day-care centres to secondary and tertiary hospitals—in 20 or more countries, but also become the most preferred one-stop shop for all ailments and diseases. We have set the ball rolling,” he had said confidently.

A lot has changed in two years, a good part of it thanks to hubris. Which brings us to the present.

Even before the Fortis board accepted the Munjal-Burman combine’s offer, two minority investors called for the removal of four board members and the induction of three new members. Three board members—Tejinder S. Shergill, Harpal Singh (Malvinder Singh’s father-in-law), and Sabina Vaisoha—stepped down before the EGM, while Brian Tempest resigned following the meeting.

In fact, even before the resignation of the board members, many experts had questioned the legitimacy of the board, its decision to appoint an EAC, and finally decide on the winner of the deal. “The legitimacy of the old board itself was in question, when the shareholders had moved a resolution to remove the members. The independence of the board from the erstwhile promoters was also in question. That board wouldn’t be best placed to find the right value for shareholders,” says Shriram Subramanian, founder and managing director of InGovern Research Services, a proxy advisory and research firm that assists institutional investors on corporate governance issues.

It was the board’s moral authority to have resigned when the three new board members— Indrajit Banerjee, Suvalaxmi Chakraborty, and Ravi Rajagopal—were appointed. “Whatever the old board would do, even with the cleanest of intentions, there would always be voices of concern from the public as the old members are viewed as wilful participants of the irregularities occurring during the promoters’ rule and also as the remnants/proxies of the promoters,” adds Subramanian.

As we said earlier, things are going to get a lot more confused before there’s any clarity on what happens to Fortis. There have been news reports that we have been unable to adequately confirm that Yes Bank, the largest shareholder in Fortis, wanted the bidding re-opened to provide the best deal to shareholders. (Yes Bank owns 15.14% in the company by buying out the unpledged shares belonging to Malvinder Singh. That’s another unsavoury episode in the progress of the healthcare company, but since it doesn’t directly impact the bidding war, we are not going to dwell on it.) Yes Bank has refused to comment for this story.

Other news reports say that Shivinder Singh had also written to the board expressing his dissatisfaction about the way the bidding was conducted, claiming that not allowing bidders time and space to conduct due diligence was unfair.

The board has clearly taken this last criticism to heart. In the new letter reopening the bidding process, it has been made clear that “bidders will be provided 10 days for financial and legal due diligence, and an opportunity to interact with the management and advisors who have conducted vendor due diligence for the company”.

Pai, predictably, has welcomed this move, probably anticipating better results this time around. “It’s a positive development and the right decision,” he says.

Everyone now wants to know what the bidders are going to do next. Will they raise their bidding price? Will new bidders come out of nowhere with more money? Any story worth its name should have a dark horse, though that seems an unlikely possibility right now. Given the speed at which this entire saga is unfolding, anything can happen.

We caught up with Pai soon after the fresh bidding was announced. “At this point, I have no idea what to do in terms of increasing the bid,” he says. Adding to everything else that we’ve spoken of so far, the Delhi government is in the process of capping the profit margins of private hospitals on the sale of drugs and implants. The government has issued a draft advisory seeking public comments and feedback; once that’s done, it plans to amend the Delhi Nursing Homes Act, 1953, in order to introduce punitive measures, including cancellation of licence, against private hospitals flouting the new norms. Those new guidelines include a 50% waiver on the total bill if a patient dies within six hours of admission to a hospital; 20% of the bill should be waived if the patient dies within 24 hours of admission. Since Fortis has seven hospitals in Delhi, the new guidelines might spell trouble for the chain.

Despite that, the bidders want to run India’s second-largest hospital chain. For IHH Healthcare, winning Fortis could give them a bigger share in the Indian market where they currently have a JV with Apollo Hospitals in Kolkata. In early 2015, IHH acquired a 51% stake in Hyderabad-based Continental Hospitals. Later, it acquired a 73.4% stake in Global Hospitals, which has hospitals in Chennai, Bengaluru, Mumbai, and Hyderabad.

Pai, meanwhile, has grand plans of merging Manipal (which has 10 hospitals across India, one in Malaysia, and a clinic in Nigeria) with Fortis to create India’s biggest hospital chain, and owning the country’s biggest path-lab chain, SRL Diagnostics. “That alone will bring in close to Rs 200 crore worth of synergies, adding another Rs 40 to Rs 50 per share,” says Pai. He is quick to add that of course there’s a lot to be done. “This is not a quick fix and this won’t be a quick fix. Running a hospital is the job of a specialist. You need to have prior background and experience,” he says, in a thinly veiled reference to the fact that neither Munjal nor Burman is primarily a healthcare specialist.

The Delhi-based bidders vehemently disagree with this. “I have been running the 1,326-bed Dayanand Medical College & Hospital in Ludhiana, which specialises in cardiology, oncology, gastroenterology, and liver transplant, along with a medical college and nursing school for years now. Running a 32-year-old hospital as complex as this is no different from running any multispecialty chain of hospitals,” claims Munjal.

Burman, meanwhile, points to the fact that his family has been running a pharmaceuticals business for over 130 years, a high-end diagnostics business, Oncquest Laboratories, and also has home healthcare services company HealthCare at Home in its fold. “Jointly, we have enough experience in running complex businesses and also understand the synergies between hospitals, pharmaceuticals, and diagnostic centres,” says the soft-spoken Burman, who has a doctorate in pharmaceutical chemistry.

Why then did they propose a strategic sell-off of SRL Diagnostics in their offer document, when both Manipal and IHH seem eager to keep it? (Providing an exit route to SRL Diagnostics’ private equity investors is spelled out in the new bidding guidelines.)

“We have not suggested selling SRL Diagnostics to the board. Rather, we have told them that we will either keep it or sell it depending on what makes eminent business sense,” says Munjal. Since both Fortis Healthcare and SRL Diagnostics require extreme focus and undivided attention, it may not be possible for the new management to focus on both at the same time. So the duo decided to focus on Fortis Healthcare, while keeping the option to retain SRL open.

Elaborating, Burman says that was their “going-in” philosophy. “Once we understand what is going on, we may decide to change our stance depending on whether the management systems, procedures, processes, etc. are in place. We will not take an emotional decision but a rational and a sensible one,” he explains.

The two add that they will definitely provide an exit option to PE funds that want to exit SRL. “There are multiple options for us: we can buy them out, or have them bought out, but we will address their concerns within the time they expect,” says Munjal. “It is not about the money,” he clarifies, adding that they can infuse far higher sums into the hospital chain if and when the need arises. Pai vehemently disagrees with this approach. What Fortis really needs, he says, is a new promoter, not just a financial investor. The Munjal-Burman combine, he says, is “not taking the responsibility to clean up the company”.

In fact, says Pai, the Munjal-Burman offer “only partially solves the short-term liquidity concerns of Fortis, and fails to deliver any longterm benefit or solve the larger issues facing the company, including in particular Fortis’ payment obligation for the acquisition of the relevant Indian entities from RHT and the exit required to private investors of SRL”.

RHT was started by the Singh brothers to create an asset-light business model where the land and property would remain with the trust, while Fortis would provide the doctors and nurses. Today, 16 such hospitals and some other divisions are in RHT and it would need nearly Rs 4,650 crore to bring them back into the Fortis fold.

All bidders are unanimous about the need to buy out the Indian entities from the RHT not just to shore up the finances of Fortis, but also staunch the flow of funds as fees to the Singapore-based business trust.

While the Munjal-Burman combine plans to bring in a rights issue to buy out the hospitals, Pai is categorical that Manipal will honour the commitment made by Fortis to acquire RHT on schedule. Even IHH Healthcare said in its bid document that it would work with the board, EAC, and other shareholders to identify mutually-beneficial instruments, not limited to preferential allotments, rights issue, a combination and other optimal means to provide a solution for the company’s funding requirements. The RHT issue has also been spelled out in the new bidding guideline.

The fight has now moved beyond the numbers. I fan the flames somewhat by asking Munjal and Burman when I meet them if their bid was the result of a Delhi clique. Since the Singhs, Munjal, and Burman belong to the same region and probably meet socially, it seems a fair question. Munjal vehemently refutes this, saying that he would not pump in crores of his and Burman’s personal funds into a face-saving exercise.

Before the new round of bidding had been announced, the Munjal-Burman combine had talked bravely about taking Fortis to court if the deal was not honoured. That doesn’t stand now, of course.

Meanwhile, can Fortis manage to stay afloat till its future is decided? At the last analyst call, Fortis admitted that it had only Rs 70 crore in its reserves, which is not enough to last it even a month.

When I met him, Munjal had claimed that: “If the current deal does not go through now, there will be no hospital chain left to bid for. Doctors and nurses will leave and a national asset will go down the tube, which the country cannot afford at this point of time.”

At the time of writing, most of the people involved in this drama say that it’s more than likely that Fortis will get a bridge loan from its biggest shareholder, Yes Bank, or its biggest lender, Standard Chartered Bank. Neither bank would comment on this.

In all this chaos, one thing seems clear; if the new round of bidding ends as badly as the earlier one, India’s second largest hospital chain could be on life-support for a long, long time.

(The article was originally published in June 2018 issue of the magazine.)