Mukesh Aghi goes to work

ADVERTISEMENT

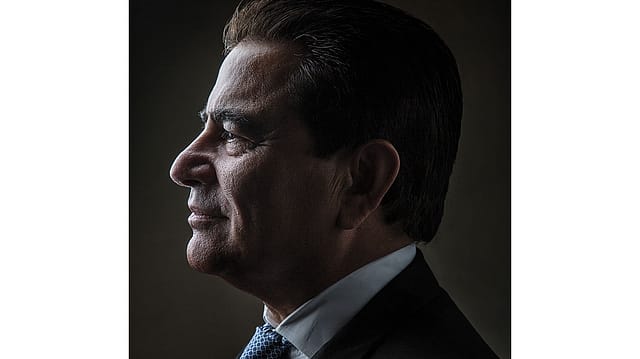

THE MAN IN THE IMPECCABLE BLACK SUIT, white shirt, blue tie, and golden cufflinks is reminiscing about watching cannons fire and bullets fly during the civil war in Lebanon where he went to college, his voice calm, his hair flawlessly coiffed, and his brow furrowed with the practised intensity of a storyteller—and all I am thinking is, oh boy, you should have been in House of Cards.

I am hung over from binge watching Netflix’s ode to White House intrigue when I get the invite to meet him. My head is swimming with images of lobbyists striking deals that require a chilling lack of scruples. At one point during the interview, I tell him, a whole generation will grow up with House of Cards as their only window into how global trade is brokered. Scarier, it seems much too real. Consider the intrigue engulfing your own job. First there were reports that the Indian government issued private assurances that it will not impose the compulsory licensing clause on American pharma companies. Then the Indian defence minister made a terse statement that there’s no question of India jointly patrolling Asia-Pacific waters with the U.S., notwithstanding a comment by a U.S. admiral that seemed to hint otherwise. Finally, there is the fierce brinksmanship over H1B visas. How do you prevent intrigue from derailing your agenda, much of which involves two countries going through diplomacy’s routine grind?

I am expecting spin. But Mukesh Aghi, 60, who went from high school in Roorkee to the president’s office at the U.S.’s biggest bilateral agency, gives me disarming vulnerability. “Let me tell you about the compulsory licensing issue,” he says, bending his athletic frame forward to meet my gaze. “I am getting calls from the [Indian] government saying, ‘You put us in this position.’ I know parliament will open soon. The opposition will question the government. My only thought right now is, how do we save face for the government, our partner.”

January 2026

Netflix, which has been in India for a decade, has successfully struck a balance between high-class premium content and pricing that attracts a range of customers. Find out how the U.S. streaming giant evolved in India, plus an exclusive interview with CEO Ted Sarandos. Also read about the Best Investments for 2026, and how rising growth and easing inflation will come in handy for finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman as she prepares Budget 2026.

Aghi’s previous job was dull in comparison. Before he took charge as the first Indian president of the U.S.-India Business Council—which germinated in 1975 based on the vision of then U.S. secretary of state Henry Kissinger, at the behest of the two governments—he was stationed in Princeton as co-CEO of the Mumbai-headquartered IT firm L&T Infotech. “I would probably have stayed a bit longer,” he tells me, reflecting on the stint from September 2012 to February 2015. “We had built a global team, positioned the company for an IPO.” (That IPO hasn’t materialised, but that’s another story.) But then came the call from Washington D.C. with a much grander job description: Influence policy that will help boost trade between India and the U.S. to $500 billion (Rs 31.6 lakh crore) by the end of the decade. “The decision was, do I want to make a few more million dollars in an IPO or build something bigger,” says Aghi. “It was a question of legacy.” He spoke to L&T chairman A.M. Naik and said yes to D.C.

The move landed him in elite company that any aspiring lobbyist (the preferred term these days is ‘advocate’) would kill for: The USIBC board that Aghi reports to is chaired by Cisco chief John Chambers and co-chaired by Edward Monser, president of Emerson Electric, and Puneet Renjen, CEO of Deloitte Global. Others on the board are an equally imposing who’s who of Indo-American business: Ajay Banga, president and CEO of MasterCard; Anand Mahindra, chairman of Mahindra Group; Francisco D’Souza, CEO of Cognizant; Indra Nooyi, chairman and CEO of PepsiCo; Shantanu Narayen, president and CEO of Adobe; James Umpleby, president of Caterpillar; and Kenneth Frazier, chairman and CEO of Merck. There’s also representation from Walmart, Boeing, KPMG, Lockheed Martin, IBM, and GE.

With this armada at its disposal, USIBC hosts some of D.C.’s most muscular shows of strength, starring everyone from Mukesh Ambani to John Kerry. Last year, just before Aghi’s appointment, working with Indian industry lobbies, it brought together President Barack Obama and Prime Minister Narendra Modi for the first joint address to the two countries’ business communities during Obama’s historic second tour of India—the only instance of a sitting U.S. head of state visiting India twice.

To be fair, it was the signing of the Civil Nuclear Deal during the George W. Bush-Manmohan Singh years that gave the relationship between the two countries the biggest fillip in recent history. Under then president Ron Somers, USIBC relentlessly lobbied for the deal in Congress and ratcheted up support from key corporate partners. ‘123’, as the deal was called, thawed the freeze in Indo-U.S. relations in the wake of India’s nuclear tests in the ’70s and the ’90s. In a 2007 story, the Washington Post quoted a zealous Somers comparing 123 with the “Berlin Wall coming down”.

With both governments showing resolve to see it through despite massive opposition from alarmists, the deal boosted the camp that believed business must decide the course of modern diplomacy. It’s a difficult shift in mindset; India and Russia, traditional friends, have failed to translate their bonhomie into a robust trade relationship owing in no small measure to meddlesome governments and the absence of strong business advocates (see ‘Russia’ in the December 2015 issue).

This is where the combined might of Aghi’s board, and their skin in the game, could make a big difference. When I met Diane Farrell, acting president of USIBC before Aghi, on the sidelines of Obama’s last visit, she signalled the same intent: “The idea that keeps coming up while describing the relationship between the U.S. and India is ‘the world’s oldest democracy [U.S.] and the world’s largest democracy [India]’. That needs to change to ‘the world’s two strongest trading partners who celebrate democracy everyday’.”

And trade has blossomed, crossing $64 billion in 2014-15 according to India’s Ministry of Commerce, and poised to touch $500 billion—USIBC’s target—by 2025, per consulting firm PwC and the Indo-American Chamber of Commerce. USIBC member firms have led by example: Since Modi took office, they have invested over $15 billion in India, and another $27 billion is in the pipeline over the next two years.

“Our two nations have a long history of shared values,” says Aghi. “Somehow our stars were never aligned, until now. India needs a trillion dollars just for infrastructure. Which other country has that kind of capital except the U.S.? India is committed to 40% renewable energy by 2030. U.S. has the technology. My job is to make sure that U.S. policies are in India’s favour without going against U.S. interests, and cajoling folks in India to work together without appearing subservient to a larger power.”

Simple enough. Except the honeymoon period of his tenure, if there were such a thing, is at an end. Like any chief executive, Aghi will now be judged not by big ideas but by how much of a dent he is really able to make in the frankly gargantuan half-a-trillion-dollar trade target. In pure stature, Somers is a tough yardstick for any successor. He is one of the tallest authorities on India in the U.S. who lived in India for 12 consecutive years. During his decade-long tenure as USIBC chief, he brought to bear his intricate knowledge of key sectors of the Indian economy, such as power and oil and gas.

Aghi’s résumé has weight—over 25 years’ experience leading complex operations at large global corporations, from enterprise software maker JD Edwards to IT giants IBM and Steria, across geographies as diverse as Japan, Singapore, India, the U.S., and Europe. But what would inspire more confidence in Chambers and Co. is his doughtiness: Notwithstanding the Hollywood-star looks, this isn’t a guy unaccustomed to rolling up his sleeves.

After college Aghi took a job as a salesman in Sweden, but his favourite sales story is from JD Edwards. “I was selling application software in Japan. At the time, the Japanese believed application software was like used toothbrush. They were only interested in custom software. People said, ‘Mukesh, you don’t have a chance’.” The first 16 months he was a total failure. “I didn’t sell anything. But I wasn’t trying to sell. I was trying to change the culture, and in time we became very successful.” After Japan, Aghi went on to open up the Singapore and London markets for the firm.

“Mukesh is leading the council at a pivotal time in U.S.-India relations, and his leadership has made a difference in a relatively short period,” says Ajay Banga, USIBC’s immediate past chairman who helmed the executive search process that led to Aghi’s appointment. The council has added several new policy verticals, like manufacturing, hospitality, and logistics. There has also been a series of bilateral dialogues in critical areas including cyber security, defence, clean energy, and smart cities.

But Aghi’s real test lies elsewhere. For starters, he has inherited an organisation beset with “structural problems”, says Nishith Acharya, who served in the Obama administration as director of innovation and entrepreneurship and senior advisor to the secretary of commerce, and now runs a consulting firm called Citizence in the U.S. “USIBC mostly represents the Fortune 500 and hasn’t done much for small and medium businesses, which are the backbone of both economies.” Last year, USIBC launched the U.S.-India Business Centers that would provide advisory support to small American businesses looking to enter India. But it is too early to determine impact.

Though the U.S. is India’s second-largest trade partner, it has actually lost ground: Till 2007-08 it was on top, show Indian government data, before being dislodged by the United Arab Emirates, which too was later upstaged by, inevitably, China (Indo-Chinese trade breached $72 billion in 2014-15). Aghi admits there are “no guarantees” that the newfound momentum will continue after the imminent regime change in Washington, going by the protectionist mood in the country (though that is de rigueur during every election). The news flow on serious disagreements on critical issues has only made things tougher.

India’s position on intellectual property rights is a major flashpoint. The country has a compulsory licensing law by which it can compel any foreign pharmaceutical firm to license its formulations to local players during a national health emergency. Pharma MNCs have often seen red at what they perceive to be a threat to precious IP. In 2014, Pfizer and Roche allegedly quit USIBC in a huff, protesting the council’s role in shielding India from penalties for its weak stand on IPR violations. Soon after, Somers stepped down as president, stoking speculation that the council was losing trust among key stakeholders.

Earlier this year, a story surfaced claiming New Delhi has secretly promised the council that it will waive the compulsory licensing clause, ostensibly under pressure from Big Pharma. “India as a sovereign country has the right to protect its citizens’ interests at the time of crisis. No one can question that,” offers Aghi. “But you also need to give certain assurances to companies that are investing billions in your country. The Indian government has only said that it respects the IPR of companies, whether Indian or international.”

A graver bugbear is New Delhi’s sloth on key reforms. Last year, Farrell had told me that the goods and services tax (GST) was the single most urgent piece of reform demanded by companies looking to invest in India. But the Modi government has failed to implement the GST, thwarted by a deadlock in parliament. “It’s a democracy. If there’s no sentiment for GST, it’s fine,” Aghi says. “Yes, our members still want it passed, but if it doesn’t happen they will adjust. For instance, they are beginning to focus on individual states [in order to bypass complicated inter-state tax structures], such as Tamil Nadu for auto, or Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat for pharma.”

On the Indian side, a big complaint is Washington’s finger-wagging on H1B visas, which threatens the business model of software exporters. There is a strong wave against H1B in the U.S., based on familiar fears that foreigners are taking away local jobs—something that maverick Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump has repeatedly tapped. “We feel the cap on visas is discriminatory and strongly oppose it,” says Aghi.

There are other areas where both countries broadly agree on the need for co-operation and yet progress hasn’t been smooth—notably defence. Aghi’s visit to India coincided with U.S. defence secretary Ashton Carter’s (like Obama, Carter too has come to India twice). The U.S. sees India as a counter to China in the Asia-Pacific and eyes chunky contracts from India’s burgeoning budget for defence goods. It has also pushed India to sign the Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Understanding (LEMOA) that will give warships and aircraft from the two countries access to each other’s bases for refuelling, repair, and other logistical purposes. But there are concerns in India that too much proximity with the U.S. could make it appear like a junior military partner, explaining the defence minister’s dismissal of joint patrolling talks.

Aghi downplays the situation; it is the closest he gets to spin during our meeting. “Defence is one of the legs of the relationship, not the main agenda,” he says. “India has to figure out how to become self-sufficient in defence. But it should also start thinking about selling products to the U.S. and its allies.”

His prescription is to take a leaf out of pharma. Indian generics have 30% share in the U.S. market, saving the country roughly $20 billion that it would have had to spend on branded drugs, he says. “We have to start using the same thinking in defence.”

WHILE USIBC’S RAISON D’ ETRE is shaping policy, a large part of Aghi’s time is spent in fighting fires that he cannot control. He says his background in IT, the world’s most disrupted industry, gives him the ability to plan for volatility. But this is a different minefield. “Look at the interest groups I deal with. There are powerful pharma companies who are saying you have to hammer home our interests. At the same time, there is the government here which has to protect the rights of its citizens. You are constantly walking a tight line,” he says. “But if you believe you are doing the right thing, you plough on.”

The sense I get is that Aghi is trying to define the “right thing” beyond the ebb and flow of corporate interests. Like Somers, he wants to cement his legacy as someone who established India as an equal in Washington’s policy corridors. In March, a resolution was introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives aiming to bring India on a par with the U.S.’s NATO allies in terms of trade and technology transfer, and elevating its status in export of defence goods from the U.S. “Some 25 countries have tried to get this designation but couldn’t,” Aghi tells me. “I was on the phone late last night strategising with the team, figuring out which Congressmen will support the move and which won’t. The odds are against us. But we are going to fight.”

His other mission is to get India into the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, a forum of 21 countries including the U.S. that promotes free trade in the region. Aghi says it is critical for India to join the group in order to maintain the competitiveness of its exports to the U.S.—especially in view of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) that the Obama administration is pushing, which, if approved by Congress, will give exporters from countries like Vietnam and Malaysia an unassailable advantage by removing export duties.

“If TPP comes into force, a lot of Indian exports and jobs will get killed. Take the garment industry. For every billion dollars in exports, the industry creates a million jobs. The TPP will shut Indian garment exporters out of the U.S. market, unless they open plants in other countries,” says Aghi. APEC membership can offset the risks. It will have an immediate positive impact of almost $500 billion on Indian exports, Aghi says, citing a Peterson Institute study. “It’s also about proving that India can compete,” he argues. “We have shown that in the services sector. The same mindset has to come into manufacturing.”

IT IS POSSIBLE TO THINK THAT Aghi is positioning himself as India’s man in D.C. USIBC professes no exclusive allegiance to either country, being completely funded by membership fees. That he is an Indian in charge isn’t remarkable either, given the rise of the Indian-American community that is less seasoned than, say, the Jewish lobby, but has come to enjoy disproportionate prominence in U.S. society and polity, thanks to the successes of Indian software professionals and doctors. But Acharya of Citizence suggests Aghi’s tenure has indeed seen a scale-back in MNC aggression towards India. “In 2013-14, during several public remarks by U.S. government officials and USIBC leaders, issues like retroactive taxation (which bothered MNCs like Vodafone), IP, and local content requirements (such as in the solar panel industry) got most of the attention.” None of these issues was more pressing than, say, finishing the nuclear deal. “But these were what I heard the most.” The implication: Aghi is rebalancing the conversation.

Nivedita Mehra, who has been with USIBC since 2006 and heads its New Delhi office, says one of Aghi’s key decisions after taking charge was to strengthen the India team, from two to six. “He wanted us to be closer to the ground,” says Mehra. “When I hire someone, I want them to be passionate about India, believe in India,” Aghi tells me. “My team has a white Caucasian male who speaks fluent Hindi, graduates from Harvard, someone who worked as a clerk under Chief Justice [Dalveer] Bhandari in Daryaganj. They are all united by their passion for bringing about change.”

Mehra adds that Aghi is pushing for a more “continuous and planned engagement with Capitol Hill”. That means regular face time with all the leading U.S. presidential contenders. “I started the process last year. After the primaries are over you will see us working much more closely with the frontrunners,” he tells me. “You have to identify which horses you want to bet your future on.” (Was he prepared for Trump? “To be honest with you, no,” he says.)

His other focus is bringing branding and marketing smarts into an organisation that could put itself out there a lot more, at least in India, considering its heft. At Steria, the French IT firm whose India operations Aghi helmed for five years (2007-2012) before joining L&T Infotech, he had a special affinity for those functions.

Sachdev Ramakrishna, then Steria’s marketing head, says the French firm had an “Eiffel Tower-centric” worldview, which led to an arrogance that customers had to find it and not the other way around. “But Mukesh said the Europeans must immerse themselves as much in India as the Americans do.” He would bring planeloads of European thought leaders who would spend three days at Steria’s learning academy in Chennai, before going off to Pondicherry to “experience the French-Indian life”. He sponsored cybersecurity summits and dinners for heads of missions, and struck up partnerships with industry opinion-makers like Gartner and IDC. He also made inroads in global power centres, from 10 Downing Street to the Spanish royal palace to the World Economic Forum. In the process, Ramakrishna says Aghi may have developed greater clout than the company itself.

Some of his actions would have ruffled feathers. Having come from IBM, where he headed India ops from 1995 to 1998 under the legendary Louis Gerstner, “a hundred thousand dollar marketing investment was par for the course for Mukesh,” says Ramakrishna. “But for a more introverted European organisation, it would feel like breaking the bank.”

Ramakrishna hints Aghi could have done more in other areas, particularly with negotiating Steria’s complex Franco-British hierarchy: The British part came from Xansa, an IT firm that Steria had acquired. “Sometimes, because we had not adequately consulted our overseas colleagues, they would slow the wheel down,” says Ramakrishna. “Could he have been more assertive at such times? Perhaps yes.” He puts it down to Aghi’s impatience with the nitty-gritty of operations. “He isn’t a man of detail. He enjoys the larger theatre.”

At least once in his career, the search for that theatre backfired. From 2002 to 2007, before his Steria stint, Aghi tried to build an online education startup called Universitas 21 that conducted MBA programmes among others. U21 had a chance to pioneer an entire industry, but it never took off. A peer of Aghi who declined to be named says “it was a mistake for him”. “It was too far ahead of its time,” Aghi concedes. It was a bitter pill for a man who says he likes changing jobs when he is at the peak of his game. “But I have always believed that you never stop learning.”

WHEN AGHI'S TEAM E-MAILED HIS PROFILE TO ME, I was struck by the way it described him: mountaineer, marathoner, golfer, and USIBC president, in that order. He has run punishing marathons, including one which sapped him so much that the doctor had to inject six bottles of fluids to revive him. He ignored the doctor’s warnings and completed the run. As a climber one of his recent conquests is Mont Blanc, Europe’s highest and deadliest peak where 100 trekkers die every year on average, even though it is not the most arduous climb in the world. “People die because they don’t respect the mountain,” Aghi says.

Aghi honed his survival instincts as a college student trapped in a civil war. “I decided to go to Beirut and not the U.S. or the U.K. because it was the centre of East and West,” he tells me. The American University of Beirut was known as the Harvard of the Middle East. But the war changed everything. “When you find your room-mates have been shot because they were from a certain religion ... it’s a terrifying experience. But you grow up. You become street smart. You try to keep your sanity by focussing on your schedule. You can panic and say, hey I am bailing out. But I hung on. I wanted to help people.” Then, perhaps sensing that the picture he is painting is a tad filmy, he adds with a chuckle: “Well, the airport was on the other side of the city, so it was difficult for me to leave anyway.”

The experience would have mellowed anyone. With Aghi, it would explain why, despite his networking chops, he has largely stayed away from media glare, or why he wants to be known as a “jazz musician” rather than an orchestra conductor trying to control things with a baton. Mehra of USIBC’s India office says he is completely “hands-off” as a boss. Other close associates, for instance Vivek Chopra, who led L&T Infotech with Aghi, describe his working style as “people-centred”. Over the phone from the U.S., Chopra lists qualities that make Aghi a natural fit for a job that requires working with the bureaucracy: “highly personable, collaborative, and focussed on business outcomes”.

Ganesh Natarajan, CEO of the Pune-based IT firm Zensar, has known Aghi for over a decade. “He is just a really nice guy,” Natarajan tells me. “But he also carries himself with lot of gravitas. He doesn’t get easily excited. I think it is this combination that makes him ideal to run a place like USIBC.” Mehra seconds that. “You have to understand that in his position, everyone wants him to react. And he tells us never to react. It is a huge leadership quality.”

Ultimately, given the noise surrounding his job, it’s the quality that could decide Aghi’s legacy. American and Indian diplomats and business advocates have been very loud and opinionated, and it has often set the relationship back (remember the fracas around Devyani Khobragade?), says Acharya of Citizence. “By lowering the tone, Mukesh has set the standard.”

Many CEOs make natural business advocates. Aghi has a unique qualification: a Ph.D. in international relations from Claremont, where his guide was the father of modern management, Peter Drucker. But it’s not the degree Aghi credits with shaping his career. Drucker dispatched him to work with U.S. House of Representatives Speaker Tip O’Neill, a legend in American politics and the second-longest serving Speaker in House history. “It was a rude awakening,” Aghi recounts. “I came from academics and wanted to change the world. Working in politics made me realise that the world cannot be changed so easily.”

It’s an epiphany straight out of House of Cards. But for the sake of the 21st century’s defining partnership, I am hoping that’s just coincidence.