The new world of Kering

ADVERTISEMENT

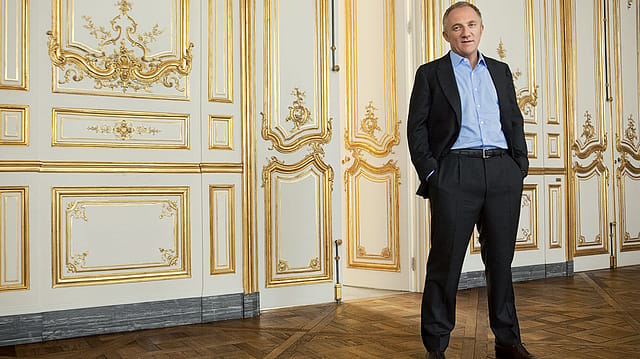

PARIS THE CITY OF cigarettes, champagne for breakfast, and pencil thinness. In this city, François-Henri Pinault comes across as more traditionally Gallic (think Gérard Depardieu) than Parisian hip (Saint Laurent Paris perhaps). The British media has often described him as a bear: a nod to the heft of his shoulders, the full face, the broad, thick arms, and a handshake that feels more like a bear hug. Appearances apart, Pinault’s also a strong-willed and remorseless adversary who has discarded big-name designers who haven’t delivered, and torn down parts of his empire to remake Kering, the luxury conglomerate he runs.

I meet him on a Wednesday morning at his second-floor office on 10 Avenue Hoche, Paris 8th, a short stroll from Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, France’s avenue of serious fashion, where aficionados mingle inside boutiques, while Champs-Élysées soaks up the tourists. Pinault’s room, otherwise unremarkable, is awash in sunlight streaming in through bay windows. His desk, on the extreme right, is almost paper-free. When he sits on one of the stiff-backed chairs, Pinault leans back, stretching out his legs like a man used to demanding, and getting, space. Last year, Kering (till recently Pinault-Printemps-Redoute, or PPR), reported profits of $1 billion (Rs 6,189 crore) on revenues of more than $10 billion, making Pinault one of the richest men in France. Pinault though, in keeping with the ordinariness of the room, is dressed simply in a pale blue shirt and dark trousers.

“If you met me a few years ago, I would have been in a suit and a tie. But our world is changing,” he says with a shrug. Change is a seditious notion in his world. Inherent to the promise of luxury is the idea of status quo: The industry embraces the vagaries of fashion, but structural changes move at a glacial pace. But in the last five years, that belief has been increasingly challenged, pushing proprietors like Pinault to dispassionately examine how they run their empires.

January 2026

Netflix, which has been in India for a decade, has successfully struck a balance between high-class premium content and pricing that attracts a range of customers. Find out how the U.S. streaming giant evolved in India, plus an exclusive interview with CEO Ted Sarandos. Also read about the Best Investments for 2026, and how rising growth and easing inflation will come in handy for finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman as she prepares Budget 2026.

Pinault says the future of luxury is a “big, big, big question”. This from a man who owns fabled labels such as Italy’s Gucci and Brioni; France’s Saint Laurent Paris and the 155-year-old jeweller Boucheron; the 222-year-old Swiss watch maker Girard-Perregaux; fashion labels such as Stella McCartney (U.S.) and the British Alexander McQueen; and Qeelin, the jeweller from China. “We are in an age of new self-expression. We cannot think of luxury anymore in terms of something merely expensive, something superficial. It is something people need to keep the dream of a better life alive. That embodies the idea of luxury, and so the biggest change is that luxury has gained a lot in authenticity and sincerity. Certain brands are mostly about marketing. This cannot work over time,” he says.

Much of this is now accepted wisdom—that the age of gimmicky marketing is over. But that doesn’t only mean shedding the logo overkill of the early- to mid-2000s. Luxury brands also have to acknowledge that to build and sustain global businesses they need far more strategic thinking than merely having lovely shop windows showing off beautiful products. And Pinault has been one of the first big CEOs to concede this shift.

In the past eight years, he has recast the empire inherited from his father to focus on luxury and sports. François Pinault, a timber merchant, who built a fashion and retail giant through a series of acquisitions, including department store Au Printemps SA and mail order major La Redoute (putting the P, P, and R together), handed over its running in 2003 to his son, François-Henri Pinault. The son promptly sold Printemps in 2006 along with other parts of the old PPR empire, such as tech retailer Surcouf (2009), discount furniture retailer Conforama (2010), and parts of another mail order company Redcats USA (2012). This January, he announced that La Redoute would be sold by the end of the year.

He also re-imagined Pinault-Printemps-Redoute’s journey to PPR first, and now, to Kering. Though Pinault’s name is no longer on the store, the new name comes from the old Breton word (a French dialect spoken in Brittany)—‘ker’ means home and ‘ing’ to suggest a home that is moving, or the sense of evolving pedigree. That it phonetically resembles the English ‘caring’ is no coincidence.

Former Puma CEO Jochen Zeitz, who is now on Kering’s board (PPR bought a controlling stake in Puma in 2007), says Pinault is doing what was long awaited. “He realised that unless he left low-margin assets, he couldn’t focus on the high-profit business, which is luxury. In a tough world, such focus is the only way for a group as large as Kering to grow.” This hasn’t been easy. The designers who have moved out have accused Kering of becoming too businesslike, while angry employees have mobbed him, protesting cutbacks.

But as long-time friend and Kering group managing director Jean-François Palus, who was a year senior to Pinault at HEC Paris, one of France’s best-known business schools and an acknowledged hub of luxury management, says, “FHP [as his pals call him] takes decisions unafraid of tradition. This has a direct impact on stock prices.” Between September and November, as news trickled in that Pinault was demerging and then selling Fnac, the DVD, books, and games chain, PPR’s (it was still PPR then) stock rose nearly 15%. Each shedding of retail businesses for a sharper focus on luxury has brought share price prize to Kering. Over all, in these past five years, the stock has risen 82%.

Last October, at a press meet Pinault explained, in great detail, his thinking. He started the conversation by saying that sometimes even some of his big investors ask him about the focus on his “choice of luxury” and his choice of sport, and why not any other segment in clothing. Pinault said that over the last 50 years, 800 million consumers, all from Western Europe, the U.S., and Japan, have driven growth in his industry. But he’s betting that the next wave over the next half-century will come from an additional 3 billion consumers, mainly from China, India, Indonesia, Brazil, and Mexico.

He said the challenges and opportunities are unprecedented. “This is why this strategy and vision have been constructed on these—what I see as fairly straightforward, fairly obvious factors worth gambling on.” Pinault threw around plenty of numbers to make his point and the dialogue was peppered with lines like “by 2020, consumption should triple in India and China”.

Those who know him in Paris say he’d have thought through Kering’s next moves very well because despite who he is, the labels he owns, or the friends he has (the international jet set), Pinault is ultimately a no-nonsense businessman, much of whose wealth is tied to the company’s stock. Palus says Pinault is an operations man at heart. He points out that during Pinault’s first visit to Casellina (the Gucci production centre in Florence, Italy), “François surprised the Gucci workers because he spoke at length about the manufacturing process and wanted to know more about it. He spent all his time in the atelier.”

TO PULL OFF his grand strategy, Pinault will need to spend more on key brands and create an organisation that can deliver to all those customers. As buyers get more diversified, luxury companies are pushing towards it. In 2008, Pinault pointed out to his team that there was only one non-French manager among 160 at its Paris headquarters. Today, there are 17 nationalities, accounting for half the managerial strength.

In 2010, Pinault also launched a gender-equality leadership programme (in part inspired by his wife, Hollywood A-lister Salma Hayek) which has ensured that in recent years women make up 56% of new hires into Kering.

Kering has also taken a leaf out of LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton’s book and is positioning itself as a sustainable brand. Its achievements include Gucci becoming the first luxury brand to introduce leather untreated by metallic substances, gems and stones, and leather only from ecologically renewable sources. Chief sustainability officer Marie-Claire Daveu says the luxury goods industry has been late to recognise its ecological responsibility, but that’s changing. “Consumers are increasingly becoming aware that their purchasing power is influential.” The new customer wants a different set of sustainabililty ethics, adds Pinault. In 2009-10, a global consumer study done by Grail Research, a U.S.-based market intelligence company, found that 85% of consumers bought sustainable or green products. Crucially, 61% bought a brand despite the economic downturn if they felt that it supported ethical businesses.

If one part of Pinault’s approach involves shedding businesses, the other entails pumping in more capital into what remains. Last year, he invested nearly €442 million (Rs 3,647.8 crore), up 75% over the previous year, in Kering. Of this, €337 million was soaked up by the luxury division, doubling investments over the previous year. Much of this went into opening new stores—53 for Gucci and 26 for Bottega Veneta. There were 122 store additions including 42 in China (Mainland China, Hong Kong, and Macau) and 19 in other emerging markets.

Then, says Thomas Chauvet, luxury goods analyst at Citi in London, who tracks Kering closely, Pinault has also realised that the way forward for Kering is to buy smaller luxury companies, invest in their growth and take them to scale. “That is a business of far greater margin.” He points to the revival of brands like Saint Laurent and the sharp rise in the fortunes of Bottega Veneta which gives Kering fire power. A reported investment of around $150 million in 2001 to buy Bottega Veneta, which then had revenues of around $50 million, has been profitable; it brought €949 million in revenue last year. Chauvet says Pinault is hoping the same will happen with high-end Italian menswear label Brioni, bought for €413 million in 2011. As young Italians lose interest in the craftsmanship that goes into handmade luxury goods, Pinault isn’t alone is picking up storied Italian brands. His bête noire, LVMH boss Bernard Arnault, snapped up Loro Piana for $2.57 billion in July.

Pinault’s push into luxury is understandable. Though it accounts for 64% of sales (Gucci, in turn, accounts for nearly 60% of luxury sales), its share of profits is 84%. He says most customers in Asia experiment with his brands in their thirties and, therefore, will stay with them longer, unlike Western customers who begin using his labels when they are slightly older.

(His track record in the sports business is mixed. Though in the immediate aftermath of the 2008 collapse, Puma, which accounts for nearly all of the division’s business, balanced out the fall in luxury sales, in recent years it hasn’t done too well. Puma’s net profits fell 70% last year and it seems far from its 2010 goal of a 50% rise in sales by 2015. Many analysts believe it should be sold, but it’s close to Pinault’s heart. Also, he says, in emerging markets, Puma could be the stepping stone to luxury labels.)

IN A SENSE, Pinault is trying what the best luxury brands in the world have done—sell history, not bags, belts, perfumes, or clothes.

To understand this, I went to Florence, home to not just Casellina but also the Gucci Museo (museum). Here, 13 artists hand cut, hand paint and hand stitch python- and crocodile-skin leather bags. Each handbag requires two or three crocodile skins and can cost nearly $80,000. This is also where wood artist Paolo Carniani carves and puts together the Gucci mini-wardrobes—a large wardrobe with shelves, which can be folded up and shut like a trunk. Each takes over four months to make and the cheapest costs $250,000. Gucci is Kering’s cash machine and for all practical purposes, Kering luxury is still largely Gucci.

The world of French luxury is divided: The most successful, globally dominating, and money-raking outfit is LVMH; the most classy, expensive and laden with history is Hermès; and the snootiest, Chanel. In this world, Gucci, from Italy, is an upstart and a direct challenge to French luxury from its only global rival, the Italians. Started in 1921 by Guccio Gucci—a porter at the London Savoy, he realised he could return home and make great luggage for the rich—Gucci is to Italy what Hermès is to France.

Gucci is also the brand over which the world’s most famous battle between two Frenchmen happened—a battle that’s unlikely to die down in a hurry. In 1999, Bernard Arnault tried to take over Gucci. The brand, with its iconic loafers, beloved floral patterns, and fans such as Grace Kelly, and Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, had been driven to near-bankruptcy in the 1990s and the combination of young American designer Tom Ford and business manager Domenico De Sole were trying to revive it. Worried that Arnault, known for his rapacious appetite, would subsume Gucci, De Sole approached François Pinault, who played white knight and bought Gucci, along with other brands such as Saint Lauren Paris and Sergio Rossi that made up the Gucci Group.

The takeover resulted in fundamental changes at Gucci, PPR, and the world of luxury. When Gucci was almost broke, Ford, then only in his thirties, revived it with brazen sexual iconography that made it a fashion mega brand. Among its many provocative and wildly successful excesses was a photo shoot that featured models with their pubic hair shaved in the shape of the Gucci double G emblem. It was impossible to imagine Gucci sans Tom Ford. But in April 2004, when Ford’s and De Sole’s contracts expired, they were not renewed.

Pinault (the son, who had taken over by then) says it had become evident that the vision of the two differed from his. “They wanted to run it as a tightly controlled structure where designs for all brands was finally overseen by Tom. But I was clear that it should be a group of multiple, independent, creative visions, where every brand has a separate journey, which adds to the group.” He had begun to see that the world was changing. And while he didn’t articulate this in so many words, some of the change he felt was that the ‘brand for brand’s sake’ era had peaked. The parting of ways also indicated that in François-Henri Pinault’s regime, the overall corporation was more important than the whims of individual designers. It was a bold decision by the 41-year-old, who had taken over just a year earlier—and it came to define him as a no-nonsense CEO.

What followed was even more significant. He institutionalised what gave Gucci its appeal so that it wouldn’t have to depend on one designer. “We went back to our roots. We realised what’s really of value was our past,” says Pinault, who encouraged Ford’s successor, Frida Giannini, to revive Gucci as a luxury brand (not merely fashion) by digging into its archives. The result was the tagline: Forever Now.

The tagline was critical to strategy, says Floriane de Saint Pierre, a luxury strategy expert in Paris, who has worked for both father and son for a decade. “The fashion industry believed that Gucci would collapse without Tom Ford. But FHP ensured that the brand not only needed to move away from Ford’s vision, but also adapt to a new world order of anti-overt consumerism and stand on its own.” With Forever Now, Gucci indicated that it was great not just in one period—it had deeper values that it wanted to present to its customers, says Pinault.

The man who built this strategy for him and was as critical to Giannini’s success as De Sole was to Ford’s, is Patrizio di Marco. “Gucci in 1993 was bankrupt. It was a quintessential luxury brand but because of the company crumbling, and the infighting within the Gucci family, the luxury perception crumbled. Then Tom and Domenico saved the company. At the time, the Gucci world was dominated by the logo. Today, most of our product offering is no logo,” says di Marco.

That’s why when di Marco, Giannini, and Pinault, decided to create the Gucci Museo to put its heritage at the heart of future business strategy, they chose the 14th-century Palazzo della Mercanzia in Florence’s historic Piazza della Signoria near the Piazza del Duomo. By placing the Gucci museum at the centre of Florentine history, the brand stamped in its credibility as the prima donna of Italian luxury.

Inside the 1,715 sq. m. museum, there is no sign of the raw sexuality of the Ford era. The focus is on the first floral prints made by Gucci for the Princess of Monaco in 1966 and the customised Lincoln cars and bicycles that the brand produced in the 1960s and 1970s.

To make it a proper museum and not a brand archive, Pinault regularly sends art from his own collection, which includes a famous piece by Indian artist Subodh Gupta. The Pinaults own Christie’s, besides having a sizeable personal collection. None of this is charity. Building a museum is the latest, and perhaps, best way of explaining to customers that luxury is both priceless and timeless.

DI MARIO EXPLAINS that neither he nor his boss thinks of the world of luxury in terms of traditional, developed market vs. emerging market any longer. “There is no such thing. That way of thinking is over,” he says. “In fact, every luxury market has a mix of all kinds of customers. So we have a new strategy where we need to address different kinds of customers all in the same market all the time.”

This is an important shift, says di Marco because they no longer distinguish the customer in terms of money but in terms of knowledge. Pinault dissects the U.S. market to illustrate. “There is Beverly Hills, which has a very different client base, and then there is New York. But we also have to think of the rest of America.” The only thing to do is to create opportunities for customers to gain knowledge.

Interestingly, neither Pinault nor di Marco thinks of America as a “mature market”. It has pockets that are mature. So, while the brand will not get rid of its monogram, it is looking to go beyond the ‘double G’ monogram-seeking customer. “GG is only a part of us. It is not the whole,” says di Marco.

This signals a subtle shift, with Gucci moving away from competing with LVMH’s overtly monogrammed approach. This strategy seems to be working. In the latest report by brand researcher Millward Brown, LVMH’s brand value, while still No. 1 in the world of luxury, fell by 12% from 2011, whereas Gucci, in third spot, soared by 48%. Second-ranked Hermès stayed at the same place.

Pinault says India is now a “natural market for Gucci” as it sheds its overtly monogrammed past and embraces pure luxury. “There are buyers in India, and a large number of them, who are very sophisticated and are seeking out real experiences,” he says. He adds that, if in the West it took 10 years or more for customers to evolve from in-your-face luxury labels to understated ones, in Asia, particularly India and China, that journey takes five. For di Marco, India is the most important market that Gucci has identified after Russia, East Europe, and Latin America.

All this means that investment patterns will change, and explains Gucci’s surge in India, where it has moved in the last three years to take on LVMH, which has been in the country for more than 15 years. Today, Louis Vuitton and Gucci have five stores each in India. There are also four Bottega Veneta stores across Delhi and Mumbai. And when Louis Vuitton celebrated Diwali across all its shop windows two years ago, Gucci replied with a Made for India handbag, which sold out.

And it could mean (as the luxury world suspects) further battle with Arnault over control of emerging markets. And in spite of protestations early on in the meeting about comparisons of the size of Kering and LVMH, Pinault (just when I’m about to leave) reminds me that Arnault is often spoken of as being vulpine. “The bear and the fox, you see,” he says with a grin. “In nature, who wins? The bear.”